Dir: Wolfgang Petersen

Star: Nastassja Kinski, Christian Quadflieg, Judy Winter, Klaus Schwarzkopf

Tatort – it means “crime scene” – is a national institution in Germany, where it has run since 1970. It’s a police procedural, with a varying cast of characters: the regional channels which form ARD, contribute feature-length entries to each series, depicting their own investigators and cases. This was one of six episodes directed by Petersen, who’d find fame with Das Boot, and move to Hollywood, where he directed Air Force One, The Perfect Storm and Troy, among others. But given its longevity, almost everyone in German film short of Werner Herzog has worked on the show at some point. Others involved include Oliver Hirschbiegel (Downfall), Michael Haneke (Funny Games), Robert Schwentke (RED), Christoph Waltz (Inglourious Bastards) and even Sam Fuller (Shock Corridor).

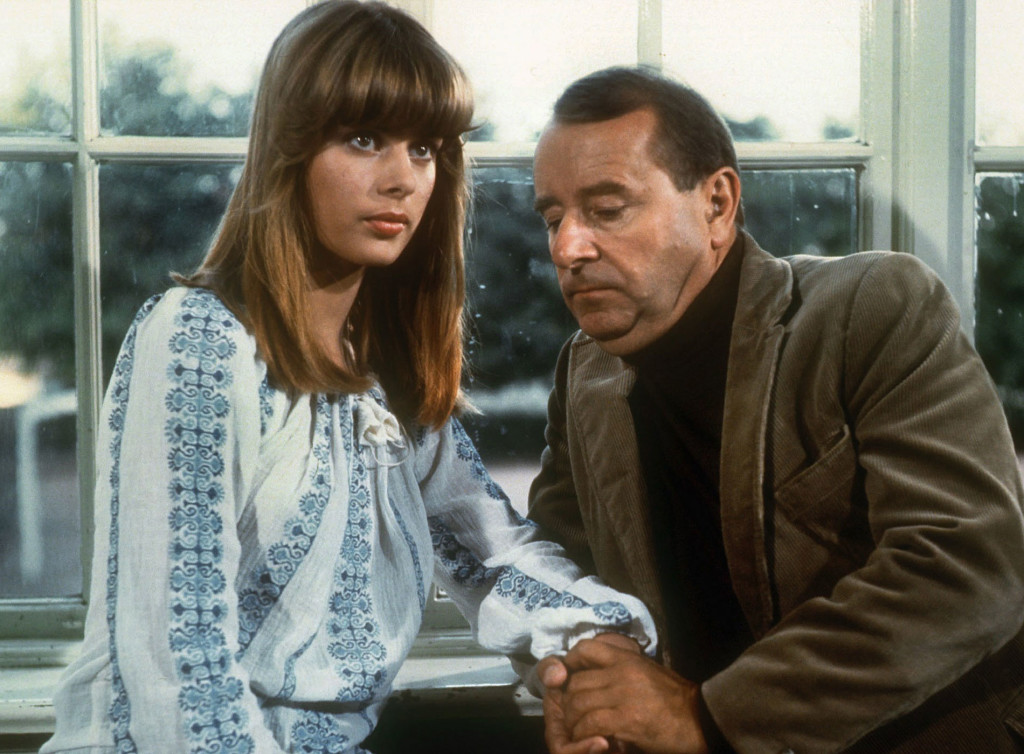

And, of course, Nastassja. She plays Sina Wolf, a teenager who is having an affair with Helmut Fichte (Quadflied), one of her teachers at the school. Another pupil, Michael, with whom she used to be in a relationship, finds out about the affair, and blackmails Sina into going to the woods with him, looking for some hanky-panky. But Sina smacks his skull in with a rock, blaming the attack on an individual she read about in the newspaper, who is being sought by the police for attacks on women. The cops, led by Inspector Finke (Schwarzkopf) are unconvinced, and the more they pick at the story, the more they find its flaws. Meanwhile, turns out Michael shared Sina’s secret with a classmate, who is now blackmailing Fichte for better grades, and things start to unravel from that end too, as his wife (Winter) finds out what’s going on.

It’s one of the few episodes of the show ever to receive any distribution outside of German-speaking territories, and it’s the only episode I’ve ever seen, so I can’t really say how typical it is. It does appear the show created quite an impact on its original screening in Germany, not least for the nudity: Kinski is topless in a couple of scenes, though is playing a couple of years older than her real age. But it is “often voted the favorite episode in Tatort’s history,” according to one source, which praises the “well-written, haunting script” and the performances, stating that Kinski “became famous overnight” as a result of the show. I can’t argue with that: it’s an intelligent story, where people behave rationally, and most of the performances are sympathetic.

It’s one of the few episodes of the show ever to receive any distribution outside of German-speaking territories, and it’s the only episode I’ve ever seen, so I can’t really say how typical it is. It does appear the show created quite an impact on its original screening in Germany, not least for the nudity: Kinski is topless in a couple of scenes, though is playing a couple of years older than her real age. But it is “often voted the favorite episode in Tatort’s history,” according to one source, which praises the “well-written, haunting script” and the performances, stating that Kinski “became famous overnight” as a result of the show. I can’t argue with that: it’s an intelligent story, where people behave rationally, and most of the performances are sympathetic.

Indeed, what’s particularly striking is how non-judgmental the film is – though it’s hard to tell how much of this is down to current morality. The movie does come from an earlier era, less (hysterically?) sensitive to underage sex. and certainly from a European sensibility – the age of consent in West Germany at the time this was filmed, was 14. though the student-teacher relationship here may have been covered by other laws. I am not an expert on German legislation, nor do I play one on TV. But that aside, it would have been easy for the creators to make Fichte some kind of sleazy predator, but he isn’t. Instead, he’s depicted almost as much a victim as Sina – who is smart and knows her own mind. She has the future all planned out.

“At 25 I will become a mother. I’ll correct English tests and when the little girl brings me the button off a coat, I won’t take it. You have to accept this. I won’t sew on buttons, nor will I iron shirts. It’d be best if you wear sweaters. In the summer, the little girl will stand in the garden and pick daisies, with a red ribbon in her hair. You will come home from school annoyed about Prof. Pfeiffer. The reason? He doesn’t like your modern educational methods. You see the child and half your anger vanishes. You see me at the door and all of it is gone.”

Teases her lover, “And if I suddenly fall in love with another school girl?” The expression on Sina’s face is marvelously deep, a million emotions flickering across her face as she pauses, before replying, firmly: “That is not a good idea.” No, what we have here hardly appears to be a seduction of the innocent. Even more remarkable – in fact, requiring more suspension of disbelief than I could manage – is the calm, rational approach taken by Frau Fichte to the news her husband is having an affair with one of his charges. She does little more than roll her eyes and request a transfer to a boys’ school. I checked in with my wife whether she would be as measured, in similar circumstances. Her stated reaction involved my testicles and a rusty nail-file, which seems more understandable. Maybe such a phlegmatic approach is a German thing.

Teases her lover, “And if I suddenly fall in love with another school girl?” The expression on Sina’s face is marvelously deep, a million emotions flickering across her face as she pauses, before replying, firmly: “That is not a good idea.” No, what we have here hardly appears to be a seduction of the innocent. Even more remarkable – in fact, requiring more suspension of disbelief than I could manage – is the calm, rational approach taken by Frau Fichte to the news her husband is having an affair with one of his charges. She does little more than roll her eyes and request a transfer to a boys’ school. I checked in with my wife whether she would be as measured, in similar circumstances. Her stated reaction involved my testicles and a rusty nail-file, which seems more understandable. Maybe such a phlegmatic approach is a German thing.

Indeed, there isn’t what you’d call a conventional “villain” in the entire movie. It’s more a tragedy for all, set in motion by a combination of small actions, none of them particularly malevolent in themselves or especially motivated by evil. Even Michael, whose attempt to blackmail Sina, is what kicks things off, is shown with some sympathy – witness the shot of him pedaling furiously away after seeing her and Helmut have sex. He’s clearly deeply hurt and angry, and his subsequent actions reflect that. Likely the most unpleasant character is Sina’s classmate, who both seeks to use the situation to her own advantage, while simultaneously denigrating Sina for her actions. Nice to know high-school bitches aren’t just an American thing.

Certainly, it’s a good deal more accessible than Falsche Bewegung, and considering it was a TV movie, has to be considered well above-average for the genre. Solidly produced and with decent performances from all the leads, it’s easy to see why it made such an impression on viewers, both in general, and in its introduction of Nastassja to a wider audience.