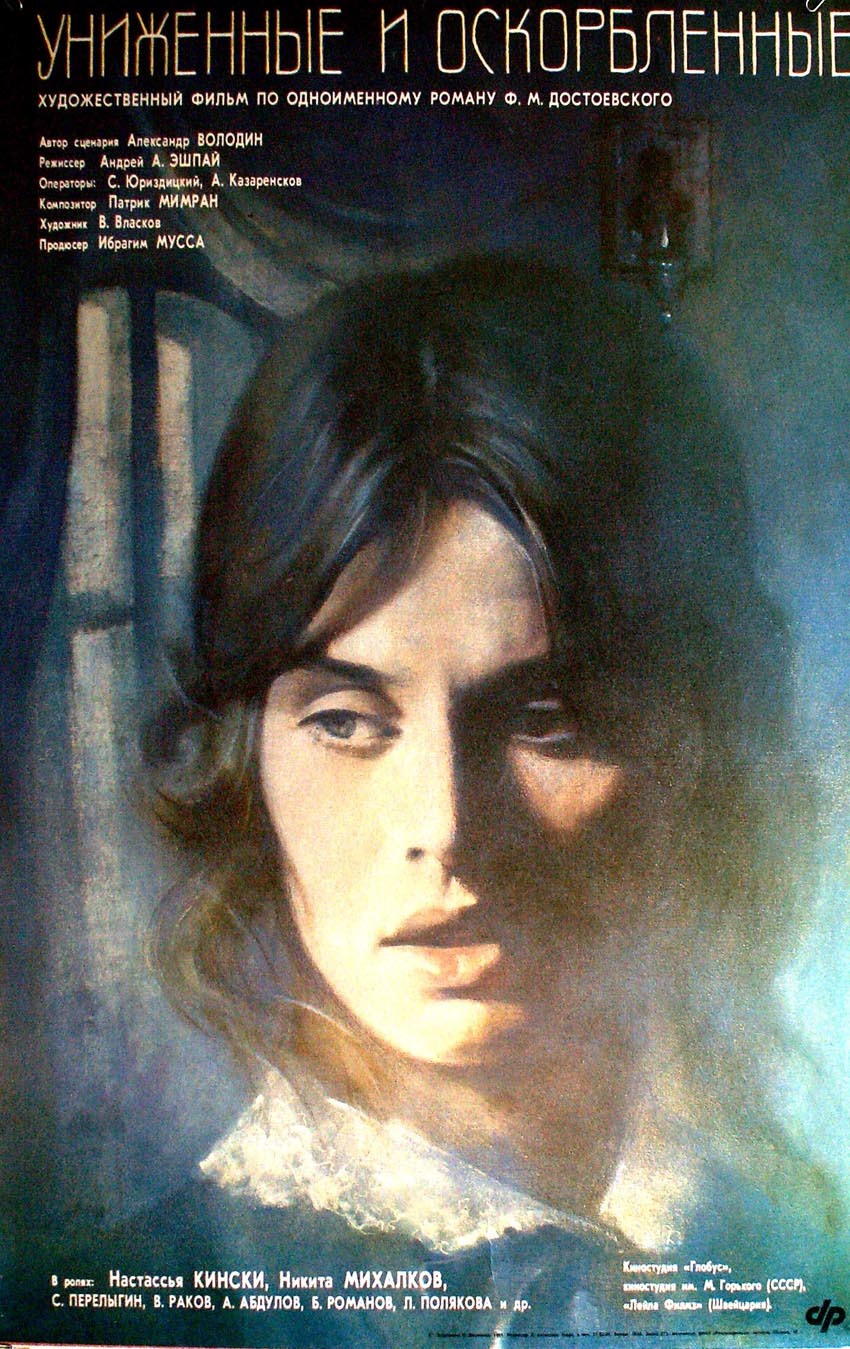

Dir: Andrei A. Eshpai

Star: Nikita Mikhalkov, Nastassja Kinski, Victor Rakov, Sergey Perelygin

a.k.a. The Insulted and Injured

My editor, Alla Savranskaya, was working for the Moscow Film Festival in 1988 when producer Ibrahiim Moussa was a jury member. She told him my film had just entered production. He said, “Did you know my wife is Nastassja Kinski?” She said, “Yes.” He said, “Did you know her children are named after Dostoevskian heroes and that she dreams of playing Dostoevsky?”

— Andrei Eshpai

Following up on Torrents of Spring (based on a work by Ivan Turgenev) and Il sole anche di notte (Leo Tolstoy), Nastassja completed the set of films inspired by Russian authors with this period drama, based on a novel by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, which was first published in 1861. And, boy, is this one a downer. By the time you reach the end, you wonder why anyone chooses to read 19th-century Russian literature, unless it is to achieve a realization that, no matter how bad your own life is, it could always be worse. That’s clear from the opening speech by the narrator, Ivan (Perelygin): “I cannot help continually recalling all this bitter last year of my life. It was a gloomy story, one of those gloomy and distressing dramas, which are so often played out unseen.” When a 19th-century Russian author starts off by telling you this is going to be “one of those gloomy and distressing dramas,” you’d better make sure all sharp objects are well out of reach before proceeding further.

Ivan holds an unrequited candle for Natasha (Kinski), with whom he has been friends for a long time. It’s in this spirit of friendship that he helps her see her love, Alessia (Rakov) in secret. Subterfuge is necessary, because he comes from a poor but noble family, and his father (Mikhalkov) has plans for an arranged marriage to Katya, the daughter of a rich family, in order to restore their fortune. In order for this to happen, he has to wreck the relationship between Alessia and Natasha, and tries various ploys to that end, hoping either for Alessia to fall for his intended bride instead, or by using Ivan to drive a wedge between the couple. Adding to the difficulty of matters, Alessia and Natasha’s father are embroiled in a legal battle that has set them at each other’s throats. Meanwhile, Ivan has taken in a young girl, whom he saved from abuse, only to find that she has a connection to events at hand too.

Ivan holds an unrequited candle for Natasha (Kinski), with whom he has been friends for a long time. It’s in this spirit of friendship that he helps her see her love, Alessia (Rakov) in secret. Subterfuge is necessary, because he comes from a poor but noble family, and his father (Mikhalkov) has plans for an arranged marriage to Katya, the daughter of a rich family, in order to restore their fortune. In order for this to happen, he has to wreck the relationship between Alessia and Natasha, and tries various ploys to that end, hoping either for Alessia to fall for his intended bride instead, or by using Ivan to drive a wedge between the couple. Adding to the difficulty of matters, Alessia and Natasha’s father are embroiled in a legal battle that has set them at each other’s throats. Meanwhile, Ivan has taken in a young girl, whom he saved from abuse, only to find that she has a connection to events at hand too.

As the quote at the top suggests, this was very much a passion project for Kinski, and remains the only Russian language film in her career. She is apparently “fluent” in Russian, according to the IMDb, but I’m not certain she wasn’t over-dubbed here, as her voice seems rather different from her other movies of the time. It’s not exactly much of a stretch for her to play the object of desire for two men, but she handles it well. Perhaps the standout moment is when she rises from her sickbed, to fiercely reject Alessia’s father. He has come visiting while she’s ill, and offers to give her back the money her father lost in the lawsuit, as “proof of his sympathy.” It’s just one of his many, similar schemes, and Mikhalkov is very effective in his role, playing someone who is unwilling to let any moral scruples get in the way of doing what he genuinely believes is best for the family. And he doesn’t care what you think.

The main problem here, is that none of the other characters can stand up to him, either in terms of the story or in cinematic presence. Alessia is a dim pawn to his father’s schemes, and perpetually vacillates between Natasha and Katya, burbling on to the former about the marvelous qualities of the latter: “If only you knew what a tender soul she is! When I think of her I always feel I become somehow better, cleverer, and somehow finer.” Ivan is probably worse still: I’m guessing Dostoyevsky took himself as inspiration, with Ivan being a struggling writer, but the way he follows Natasha around like a puppy, unable to voice his affection for her, is immensely irritating. It’s the behavior of a love-struck teenager, not an adult male, and the longer the film went on, the greater my urge to reach into the screen, back to the 19th century, and strangle Ivan.

Watching miserable people do miserable things to other miserable people, only to sink further into misery, all set against a historical backdrop that alternates between grinding poverty and moral disdain just isn’t my idea of entertainment. This kind of thing can work, shedding light on man’s inhumanity to man in a way that has relevance to a modern viewer, or simply creating memorable characters, that stick in the viewer’s mind. But it needs a clear goal as well as a firm hand to carry this off, and despite Mikhalkov’s solid work, Eshpai never gets very far off the ground, in either direction. Of the three adaptations of Russian literature, filmed in short order by Kinski, this is very much the least of the three. Perhaps a less apparently reverential approach toward the subject matter might have paid off better.

It was an incredible emotional drain and huge challenge because Dostoevsky is one of the deepest novelists in the history of literature, and the demands of the prose itself were enormous.

— Nastassja Kinski

I felt this to be much better than Night Sun. Regardless of IMDB.