Dir: Aruna Villiers

Star: Christopher Lambert, Nastassja Kinski, Audrey DeWilder, Andrzej Seweryn

Gynecologist Thomas (Lambert) rescues Mathilde (Kinski) from the side of the road, after her car breaks down, and so begins their relationship. She is more than a bit unstable, having been on anti-depressants, and already lost a son in a previous incident, whose details remain obscure for most of the movie. Mathilde is now apparently unable to have any further kids, but Thomas knows someone – Professeur Cardoze (Seweryn), who is doing some research on the cutting edge of human cloning. Without telling Mathilde, Thomas enrolls her in the program, and the couple are delighted when she becomes pregnant, and has a bouncing baby girl, Manon. The proud parents live happily ever after with their daughter, able to enjoy family life through the grace of modern technology. The End. Sorry? That isn’t what happens? I am shocked – shocked – by this development.

Remember when cloning was the Next Big Thing? Or course, there have been clone movies around for a long time; 1978’s The Boys From Brazil was probably the first to take the idea mainstream. However, there was a five-year period, roughly covering 2000-04, when they seemed particularly fashionable, including things like The 6th Day. What almost every clone film, regardless of era, seems to have in common is their cautionary nature. Whether it’s Multiplicity or Godsend, cloning is rarely if ever depicted as a boon to humanity. Stuff goes wrong, because this is, it appears, firmly filed in the box marked “things with which mankind is not supposed to meddle.” And so it proves here, inevitably.

Remember when cloning was the Next Big Thing? Or course, there have been clone movies around for a long time; 1978’s The Boys From Brazil was probably the first to take the idea mainstream. However, there was a five-year period, roughly covering 2000-04, when they seemed particularly fashionable, including things like The 6th Day. What almost every clone film, regardless of era, seems to have in common is their cautionary nature. Whether it’s Multiplicity or Godsend, cloning is rarely if ever depicted as a boon to humanity. Stuff goes wrong, because this is, it appears, firmly filed in the box marked “things with which mankind is not supposed to meddle.” And so it proves here, inevitably.

There are two particular problems, though I’m not sure either have even the slightest credible basis in scientific logic. Firstly, and most obviously, is what appears to be the accelerated rate at which Manon grows up. This is likely necessary for cinematic purposes, and I did enjoy some of the tricks which Villiers found to show the passage of time, such as having toddler Manon crawl round the back of the well in their garden, only for little girl Manon to run out on the other side. It’s hard to be quite sure about the time-frame in question, not least because Lambert and Kinski don’t appear to age a single day, but also because of Manon (DeWilder) playing ahead of her chronological age: by the end, she’s supposedly twelve, but seems to be acting more like someone in their late teens.

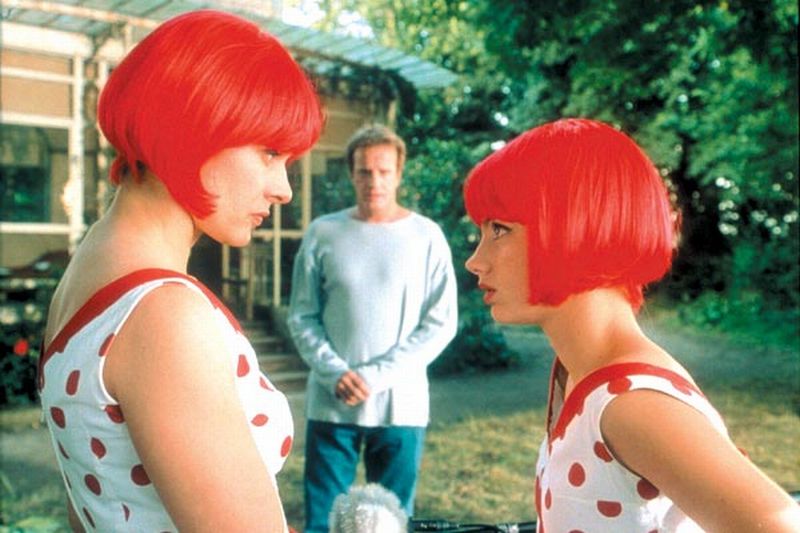

The other issue is that Manon appears have all her mother’s memories as well. At first, this cloneiness manifests itself relatively innocently, in nightmares during which Manon appears to relive the circumstances surrounding the death of her sibling, and a fondness for dressing in the same clothes as her mother – as well as performing (what can only be described as “moderately creepy”) dress-up musical numbers for Thomas, shown below. However, as she matures into adolescence, the same unstable streak which her mother had, begins to develop in Manon, and it becomes increasingly clear the daughter is intent on using this knowledge of Mathilda against her, to replace her in Thomas’s affections.

It’s perhaps this aspect which is one of the reasons why the film has received only limited distribution, not apparently receiving an official DVD release in the US or UK. [I ended up having to subtitle the film myself, based off a combination of Google Translate, and my schoolboy French!] While hardly explicit, and being produced by Luc Besson’s Europacorp studio, having a 12-year-old character attempting to seduce her father is still the kind of thing guaranteed to provoke tabloid “BAN THIS EVIL FILTH!” headlines, and the fact the DeWilder was 15 at the time of shooting isn’t likely to help matters much. This is very much the kind of approach to the topic of clones and their consequences, which would only come out of French cinema, and likely helped restrict its appeal in other territories.

Though overall, it’s not too bad, I’d say – save for a climax which topples over from the implausible into the entirely absurd, set around the back-garden well mentioned earlier. There’s a struggle between Manon and Mathilda, while Thomas lies unconscious nearby, having been whacked with a shovel earlier in proceedings. But the way the script finds to end things is so abrupt, it smells of desperation on the part of the film-makers. I’d be curious to know if the novel by Louise Lambrichs, on which the film was based, does better in this department. However, it doesn’t seem to have received an English translation either, and neither my French nor my patience are up to the task of investigating further.

Kinski is good in her role as the damaged Mathilda, drifting slowly from delight at being able to have another child into horror, into the realization there is something terribly wrong, and that Thomas has been far from honest with her. She projects the necessary air of fragility, and I could see the story going doing an alternate route, where her suspicions are rejected by her husband as paranoid delusions, stemming from her mental state. I’m not as convinced by Lambert. His iconic role as the immortal Connor MacLeod in Highlander makes it a little bit difficult to accept him as any kind of scientist. and the performance isn’t good enough to make the viewer take him seriously.

The film occupies a bit of an awkward middle-ground: the topic is pure sensationalism, but Villiers, who also worked on the script, apparently wants us to take the subject matter seriously. She never quite manages to get the audience – or, at least, me – to go along with her on that. I sense I might have enjoyed it more, if there had been a more lurid and exploitational approach, because that’s likely what the concepts here deserve.