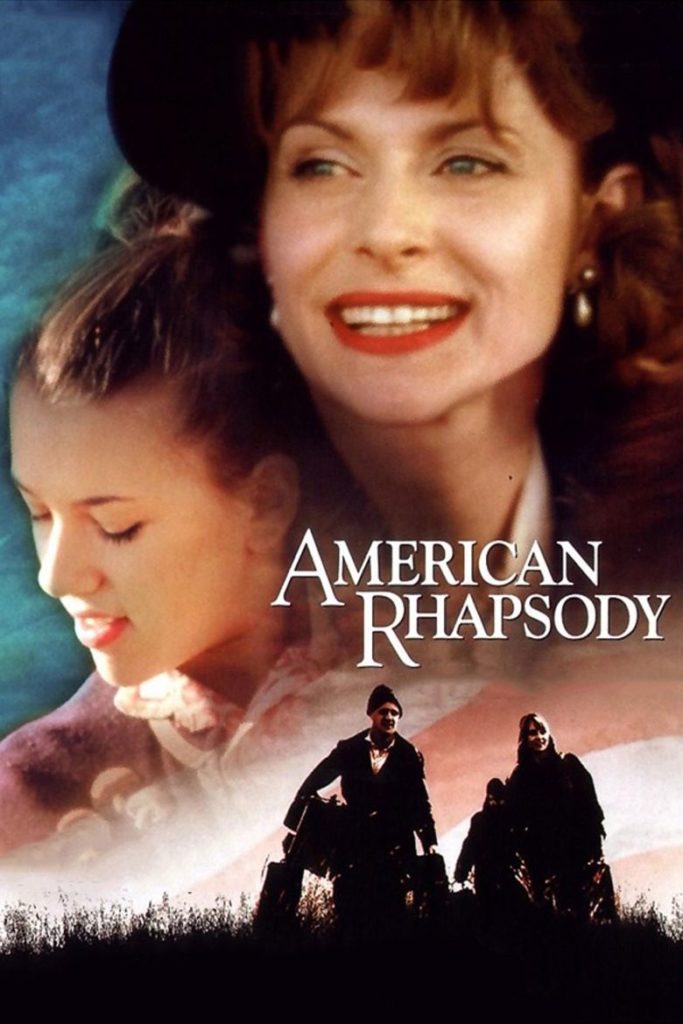

Dir: Éva Gárdos

Star: Nastassja Kinski, Scarlett Johansson, Tony Goldwyn, Kelly Endrész Banlaki

“Nastassja is amazing. I met her several years ago when Bonnie Timmermann first gave her my script. When I showed her a picture of my arrival, she understood the drama of the story. She has a lot in common with the character, as a European woman and someone who has gone through many changes in her own life. And, of course, her natural warmth and beauty make the character very complex and rich.”

— Director Éva Gárdos

In which a bratty teenager runs off back to her Eastern Bloc roots, and discovers that life is not always greener on the other side of the Iron Curtain. I may be somewhat misinterpreting the point here, and it’s certainly not all that happens in this. It’s more likely the “bratty teenager” aspect is the one with most personal resonance. Though at least our daughter never had to be locked in her room or took to shooting holes in the bedroom door, like the character here. I’m grateful for that.

I’m also getting ahead of the film here. It begins in 1950’s Hungary, a dark time when the jackboot of Soviet totalitarianism was cracking down hard on any form of dissent. Husband and wife Peter (Goldwyn) and Margit Sandor (Kinski) decide to escape across the border to the West. Their elder daughter, Maria, is just old enough to be part of the escape, but it’s too risky for newly-born Suzanne, who will take a different route. However, that falls through, and Suzanne spends her first five years being brought up by a foster family in the country. Her real parents have reached California, where Margit wages a letter-writing campaign to everyone from Eleanor Roosevelt to Dag Hammarskjöld, seeking their help to get Suzanne to America.

It eventually has the desired effect and Suzanne (at this point, played by Banlaki) is swept away from her fosters and on a plane to America, where she has to cope with suddenly having a big sister, burgers, Coca Cola, and not simply being able to wander around at will, like she did in Hungary. Fast forward a decade, and she (now, Johansson) has become an archetypical surly teenager, not enhanced by a belief her mother abandoned her. This evinces itself in smoking, hanging out with boys and shrieking “I hate you!” at her bemused mother, who has no idea how to cope. Her reaction involves calling a locksmith, which is what causes Suzanne to blast her way to freedom.

Eventually, her more level-headed father agrees to let Suzanne return to Hungary, and visit her foster family. While delighted to see her, they are now living in a Budapest apartment, and Suzanne gets to experience first-hand the failures of Communism. However, she also discovers the specific reason why her mother was unable to live in the country any longer, and gains a new-found appreciation for what her parents went through in order to give her a better life. So, it all ends in hugs between mother and daughter, because America is the bestest country in the world ever, am I right?

Eventually, her more level-headed father agrees to let Suzanne return to Hungary, and visit her foster family. While delighted to see her, they are now living in a Budapest apartment, and Suzanne gets to experience first-hand the failures of Communism. However, she also discovers the specific reason why her mother was unable to live in the country any longer, and gains a new-found appreciation for what her parents went through in order to give her a better life. So, it all ends in hugs between mother and daughter, because America is the bestest country in the world ever, am I right?

Sorry, guess my cynicism slipped through again. The film doesn’t truly deserve that – or, perhaps, it does – as it genuinely seems to believe the rose-tinted view on display. Witness how the Sandors are, one second, crossing the border from Hungary with suitcases, filmed in ominous black-and-white, and the next, they’re magically living in full Technicolor, occupying a wonderful home in California, with a car and all mod cons, even though she’s a waitress and he’s a door-to-door salesman of vacuum cleaners. Damn, if I realized emigrating to America was so easy, I’d have done it fifteen years sooner.

Fortunately, there are a few things which save it from collapsing entirely into a large tub of saccharine. Gárdos, largely inspired by her own experiences, it appears, treats everyone involved with respect and empathy. You understand both where the mother is coming from, and why the daughter feels betrayed – their actions make sense on an individual level, it’s the clash between them which leads to the dramatic tension. The performances are also uniformly excellent. First off, I don’t speak Hungarian, but both Kinski and Goldwyn seemed entirely convincing when doing so – those familiar with the language, appear equally impressed.

The emotional heart of the movie, however, is likely Banlaki, who is entirely adorable as the moppet growing up in total ignorance that her family is not her family. Watching the angst on her little face as she was torn away from them, then flown half-way around the world to a completely alien culture, and a language she couldn’t speak, was heart-rending. It is a necessary trauma for the purposes of the film, since it help you understand the teenage Suzanne’s subsequent rebellion into whiny self-pity. Johansson certainly nails that aspect, though the director claims she toned the character down: “Many times people involved in the film asked me, ‘Were you really as bad as Suzanne’ and I have to admit that; no, I was even worse!” [I also note the presence of another young future star, Emmy Rossum (Christine in the Phantom of the Opera film), playing her teenage comrade in arms, Sheila.]

Gárdos was better known as an editor, and this was her feature debut. As such, it’s not a bad effort, despite my cynical. Perhaps a little earnest and somewhat heavy on the portrayal of Communism as Reagan’s “Evil Empire,” though given the director’s background, losing no love for the Soviets is probably understandable. This reminded me somewhat of Kinski’s earlier The Ring, which was also about a family seeking to make a new life for them, by emigrating from post-war Europe. That was rather more melodramatic perhaps, and I likely appreciated this better (despite what some of my more snarky comments above may imply!). There’s a solid aura of quality here, enhanced in particular by an evocative score from Cliff Eidelman, and it’s a welcome step up for Nastassja.