Dir: Francis Coppola

Star: Teri Garr, Frederic Forrest, Raul Julia, Nastassja Kinski

“One from the Heart has no characters, no performances, no story, no comedy and no romance, only what Hollywood calls ‘production values’… [It] appears to have been originally conceived as a series of sets, then as a story to go with the sets.”

— Vincent Canby, New York Times

Kinski’s first Hollywood film was a complete box-office disaster: it cost $26 million, but grossed less than $640,000 at the US box-office, a percentage which still ranks as among the worst ever. A string of poor decisions, both production and financial, bankrupted Coppola, and resulted in him, a decade later, filing for bankruptcy and owing partner and co-producer Fred Roos a total of $71 million by the time interest was included. Perhaps worse still, attempts to pay off the debt forced Coppola into a lengthy period of artistic servitude, working on things like Captain EO for Disney, or even Jack, the Robin Williams “comedy” (and quotes have rarely been used more deliberately). No-one should have to go through that…

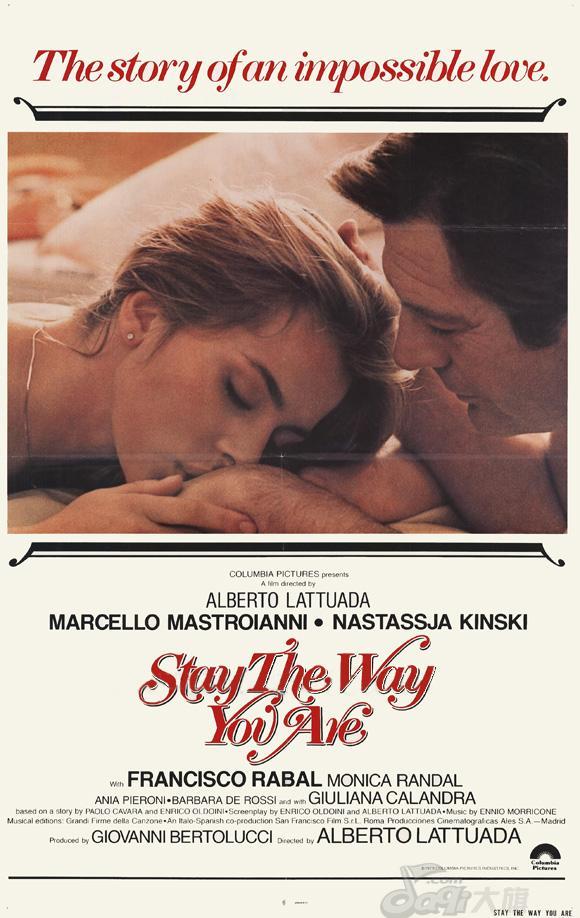

Much though Coppola deserved some punishment, since it’s hard to disagree: Heart does suck. It’s a massively ill-conceived entity, which contains about fifteen minutes of cinematic magic, sandwiched in the middle of a pair of unlikeable characters, who feel like they spend the entirety of the remaining ninety minutes, yelling at each other. They are scrap-yard worker Hank (Forrest) and travel agent Frannie (Garr), who are celebrating their fifth anniversary in Vegas. But it’s not long before their bickering turns into her storming out, and both of them hook up for one-night stands with their ideal lovers: she with Ray (Julia), a waiter and wannabe musician; he with Leila (Kinski), a circus artist. However, will this bring them the happiness they seek, or do they belong together?

Much though Coppola deserved some punishment, since it’s hard to disagree: Heart does suck. It’s a massively ill-conceived entity, which contains about fifteen minutes of cinematic magic, sandwiched in the middle of a pair of unlikeable characters, who feel like they spend the entirety of the remaining ninety minutes, yelling at each other. They are scrap-yard worker Hank (Forrest) and travel agent Frannie (Garr), who are celebrating their fifth anniversary in Vegas. But it’s not long before their bickering turns into her storming out, and both of them hook up for one-night stands with their ideal lovers: she with Ray (Julia), a waiter and wannabe musician; he with Leila (Kinski), a circus artist. However, will this bring them the happiness they seek, or do they belong together?

It’s doomed to fail from the get-go, because there is absolutely no reason provided for the audience to root for the couple. We’re not shown them loving each other, or even given anything that might make us like them, and care about their fate. They’re not together two minutes before they arguing about whether to stay in or go out, and that sets the tone for almost all their exchanges until the utterly implausible ending. Really, if this is any kind of accurate snapshot of their relationship, it’s a miracle the previous five years have not led to involuntary homicide by one or the other. Even separated, they’re no more engaging, each whining to their friends about what a bastard/bitch the other is. [Hank’s colleague is played by Harry Dean Stanton, somewhat foreshadowing his later work with Kinski on Paris, Texas].

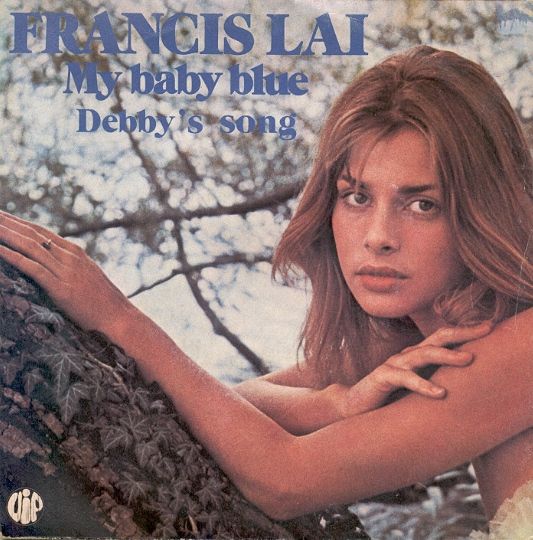

You can certainly admire the epic look and feel, with the entire thing filmed on sets at the Zoetrope Studios lot. That involved rebuilding the Las Vegas strip at a cost of $6 million, with 125,000 light bulbs and ten miles of neon. However, it doesn’t have any real sense of era: at times, it feels like the forties, but at others it could be the sixties or even the seventies. It’s as if Coppola was so obsessed with the details, he forgot the bigger picture. Still, this all pays off for at least one glorious segment in the middle, starting from when Ray seduces Frannie through dance, and proceeding through Kinski’s rendition of Little Boy Blue, and on to her hanging out with Hank at the scrapyard, which she regards as a “Taj Majal”-like wonderland. There, you can see for what Coppola was aiming. It’s a shame the rest of the film falls so far short of the same standards.

The supporting cast, Julia, Kinski and Stanton, are actually all solid in their roles. I have far greater problems with both Garr and Forrest, who are perhaps intended to stand in for the everyman and everywoman, but are badly miscast, and Coppola only succeeds in making them boring and irritating. This, combined with the idiocy of the plot. leave the film with a gurgling vortex at its core, down which everything else eventually vanishes, after varying degrees of struggle. I must confess that the setting of Las Vegas is appropriate, and has a certain emotional resonance to me, as that’s where I met my wife for the first time. The soundtrack, by Tom Waits, and performed by him and Crystal Gayle, works nicely as a chorus of comment. It’s really a musical, where almost none of the characters sing – Kinski’s number represents a rare exception.

Overall, however, this is one of those cases, where the process by which the movie was made (Coppola largely directing it from the interior of an Airstream trailer), and its after-effects, are a great deal more interesting than the actual product itself. I largely agree with Canby’s summation at the top of the page, or even Pauline Kael’s snarky assessment that “This movie isn’t from heart, or from the head either; it’s from the lab.” In Jon Lewis’s book, Whom God Wishes to Destroy…: Francis Coppola and the New Hollywood, the author suggests Coppola’s problems were the result of the studios trying to freeze out some of his advanced ideas about the way technology would revolutionize the industry.

“In order to protect their position – in order to maintain control over the distribution and exhibition of motion pictures in the United States – and in order to send a message about the shape of things to come in the industry, it was necessary for the studio to make sure that Coppola would not be able to fund his research… The production problems that plagued the film – all of which, more or less, had to do with capital secured through the major studio-big bank apparatus – seem at the very least to indicate an unstated industrywide decision to make the movie as difficult to produce as possible.”

That Coppola’s foresight was somewhat accurate (in general direction, more than specific ideas) matters not. It’s undeniable he didn’t so much shoot himself in the foot, as unload an entire magazine there. For instance, he filmed an entire additional, un-financed opening sequence without having secured the necessary cash: when he went to Paramount to ask for the extra $4 million, they turned him down, annoyed at not having been consulted beforehand. He ended up having to fund it from Chase Manhattan, with the studio and his Napa Valley winery as collateral for the loan. That ended well.

That Coppola’s foresight was somewhat accurate (in general direction, more than specific ideas) matters not. It’s undeniable he didn’t so much shoot himself in the foot, as unload an entire magazine there. For instance, he filmed an entire additional, un-financed opening sequence without having secured the necessary cash: when he went to Paramount to ask for the extra $4 million, they turned him down, annoyed at not having been consulted beforehand. He ended up having to fund it from Chase Manhattan, with the studio and his Napa Valley winery as collateral for the loan. That ended well.

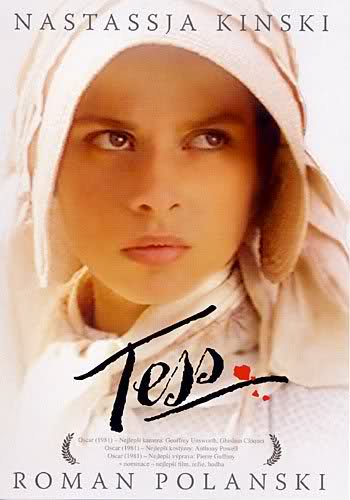

Finally, I was viewing the film in 4:3, as available on Netflix, and was wondering how that affected things, even though the cinematography certainly isn’t a problem here. However, turns out Coppola deliberately shot in that ratio, to mimic the visual style of the forties musicals he wanted. It still felt weird, because I’m so used to watching letterboxed films these days. It was certainly a contrast to go from the widescreen glories of Tess to something which both looks like an extremely expensive TV movie, and plays like a bad soap-opera.

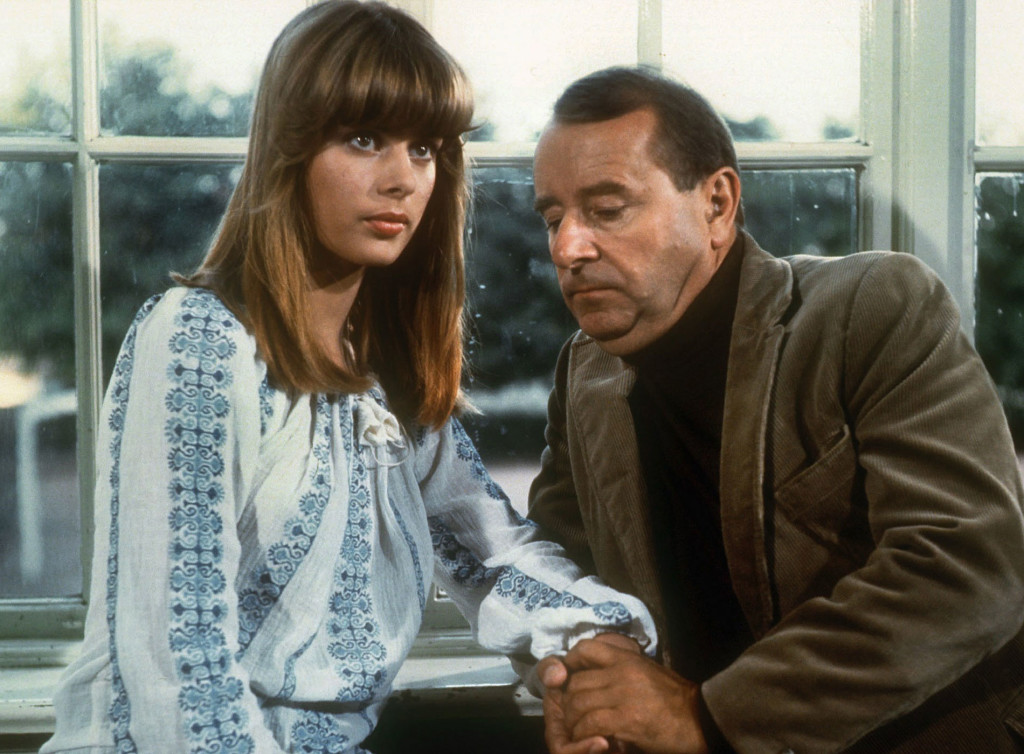

Teases her lover, “And if I suddenly fall in love with another school girl?” The expression on Sina’s face is marvelously deep, a million emotions flickering across her face as she pauses, before replying, firmly: “That is not a good idea.” No, what we have here hardly appears to be a seduction of the innocent. Even more remarkable – in fact, requiring more suspension of disbelief than I could manage – is the calm, rational approach taken by Frau Fichte to the news her husband is having an affair with one of his charges. She does little more than roll her eyes and request a transfer to a boys’ school. I checked in with my wife whether she would be as measured, in similar circumstances. Her stated reaction involved my testicles and a rusty nail-file, which seems more understandable. Maybe such a phlegmatic approach is a German thing.

Teases her lover, “And if I suddenly fall in love with another school girl?” The expression on Sina’s face is marvelously deep, a million emotions flickering across her face as she pauses, before replying, firmly: “That is not a good idea.” No, what we have here hardly appears to be a seduction of the innocent. Even more remarkable – in fact, requiring more suspension of disbelief than I could manage – is the calm, rational approach taken by Frau Fichte to the news her husband is having an affair with one of his charges. She does little more than roll her eyes and request a transfer to a boys’ school. I checked in with my wife whether she would be as measured, in similar circumstances. Her stated reaction involved my testicles and a rusty nail-file, which seems more understandable. Maybe such a phlegmatic approach is a German thing.

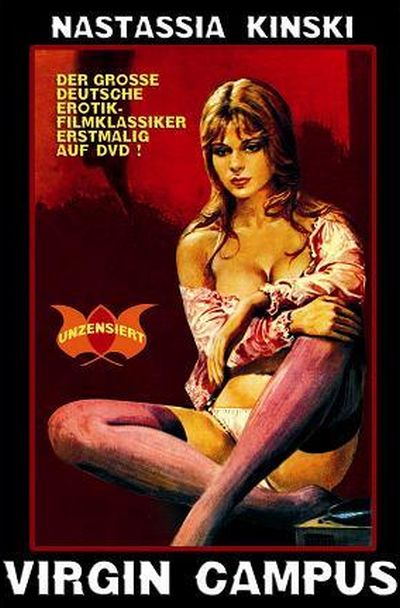

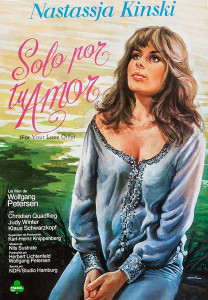

Dir: Luciano Martino

Dir: Luciano Martino