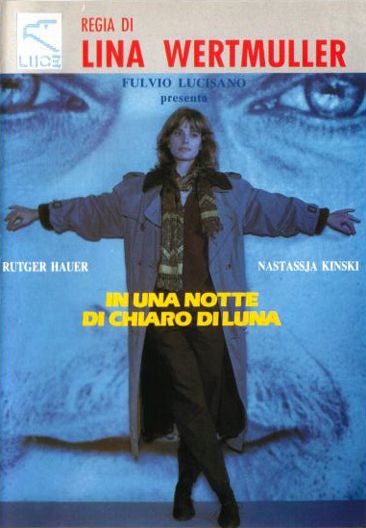

Dir: Lena Wertmüller

Star: Rutger Hauer, Nastassja Kinski, Faye Dunaway, Massimo Wertmüller

a.k.a. Up to Date

Crystal or Ash, Fire or Wind, as Long as It’s Love

On a Moonlit Night

I’ve always been a fan of Rutger Hauer, and think he’s generally a much better actor than he’s given credit. He’s best known for his work in Blade Runner, in particular the “attack ships on fire” speech at the end, which is one of the most memorable ever in SF cinema. He’s just as wonderful in The Hitcher, but as I explored his filmography beyond those two great movie villains, I gradually came to appreciate his subtler talents. Films like The Legend of the Holy Drinker show what a solid talent he genuinely is, and Hauer helps elevate what could otherwise be schlocky genre crap, like Split Second, to thoroughly enjoyable. He’s one of those actors who is always worth watching, regardless of the type of film he’s in.

I hadn’t seen this one, however. It didn’t seem to receive any significant kind of distribution. Not one IMDb review, and less than 200 votes, despite a pair of leads who were still well-known internationally, plus Wertmüller being the first woman ever nominated for the Best Director Academy Award, for her 1976 film, Seven Beauties (though she’s probably better known as the director of the original Swept Away, later butchered in a remake by Madonna). Perhaps the plot was considered a tough sell. Hauer plays European journalist John Knott, who is working on a project exposing prejudice against those infected with AIDS, by telling restaurants, priests, etc. that he is HIV positive, and documenting their reactions, along with his photographer. He’s reunited with an old flame, Joëlle (Kinski) and her young child, and they resume their relationship. But then a devastating blow descends. Know that disease he had been pretending to have? Guess what he now actually has.

He quietly arranges for Joëlle and her daughter to be tested; fortunately, they get the all-clear, but he decides that the best thing to do is simply leave them, without telling them why. He moves to New York, and forms a partnership with another victim of HIV, Mrs. Colbert (Dunaway), to work on funding research into a cure. Joëlle, meanwhile, is devastated by his apparent abandonment. Years later, John discovers she is becoming close to another friend of his, unaware that her new boyfriend is also HIV positive, and goes to confront him about behavior which is potentially lethal to the woman John still loves. Joëlle shows up in the middle of the resulting bloody brawl, and is distraught when she is chased away at gunpoint, unaware John is simply trying to protect her from the risk his contained in his body fluids. His photographer finally tells her the truth about why John felt he had to go away, and she flies to America to confront him.

He quietly arranges for Joëlle and her daughter to be tested; fortunately, they get the all-clear, but he decides that the best thing to do is simply leave them, without telling them why. He moves to New York, and forms a partnership with another victim of HIV, Mrs. Colbert (Dunaway), to work on funding research into a cure. Joëlle, meanwhile, is devastated by his apparent abandonment. Years later, John discovers she is becoming close to another friend of his, unaware that her new boyfriend is also HIV positive, and goes to confront him about behavior which is potentially lethal to the woman John still loves. Joëlle shows up in the middle of the resulting bloody brawl, and is distraught when she is chased away at gunpoint, unaware John is simply trying to protect her from the risk his contained in his body fluids. His photographer finally tells her the truth about why John felt he had to go away, and she flies to America to confront him.

This almost feels like a period piece now, set at the height of AIDS hysteria. Was it really the case that restaurants would refuse to serve HIV-positive patrons? I can’t say, as at the time, I was attending university in the North of Scotland, which was not exactly AIDS Central. It certainly seems an entirely different time, with the various treatments now available no longer making it the death sentence it once was. As a result, any modern viewer has to adopt a different mindset in order for much of this to resonate. It does also come across as fairly contrived: exactly how or where John became infected is never made clear, except for his mention that it was “on a moonlit night.” And the social consciousness on display is painfully obvious. In this world, seems that only heterosexuals get AIDS, while the only people who treat the fake-infected John with tolerance are London dockworkers. Not buying it, sorry.

What does make it work are the performances, Hauer’s in particular. He received an additional credit for work on the dialogue, and according to his official website, “While Lina Wertmüller was more interested in the social aspect of the plot, Rutger wanted to give more emphasis to the love-story.” I’m with Hauer there: John comes off as a genuinely likeable guy, and it’s painful to watch him be torn between his love for Joëlle and their daughter, and his desire to protect her from the agony of having to handle his slow, irrevocable demise. You can see why he chose to do what he did, though it causes a different kind of agony. Call it the Sophie’s Choice of romance. Kinski holds up her end of the film well, though it’s very much Hauer’s movie, particularly in the second half. Joëlle is just as devoted to John, but is unaware of the whole picture, and her mix of bafflement and despair is pitiable.

There aren’t many other films I can think of like this, and it deserves credit for being one of the earliest acknowledgments in mainstream cinema of AIDS. I guess Tom Hanks in Philadelphia might be about the closest in tone, and that came four years later; this also pre-dates Longtime Companion, which appeared the following year. I wonder if the film’s story perhaps had a long-lasting effect on its star, because Hauer would go on to set up a charity, the Starfish Association. Its website describes it as, “A non-profit organization aimed at raising help and awareness on the HIV/AIDS situation, focusing especially on support to children and pregnant women.” If so, even if the movie is largely now obscure and forgotten, its message of tolerance and love does carry on.

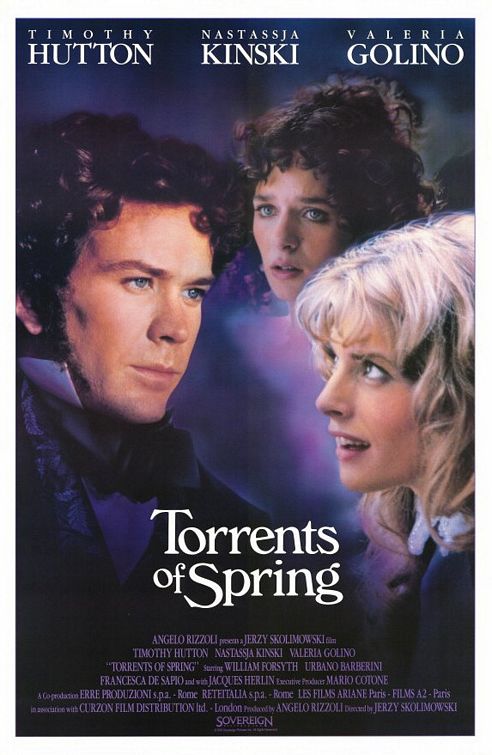

In particular, she aims at his relationship with Gemma Rosselli (Golino), who works in a pastry-shop in the German town Mainz, which Sanin is visiting. He saves the live of her brother, is invited to dinner, and the two fall in love. Which is unfortunate, since she is already engaged. However, when Dmitri shows himself willing to fight a duel to protect Gemma’s honor (even though the incident was actually provoked by Maria), she breaks the relationship off, and Dmitri begins preparing to sell his Russian estates and move permanently to Mainz. He bumps into an old friend, Prince Ippolito Polozov (Forsythe), who says his wife may be interested in purchasing Dmitri’s land – but this is merely a ruse for Maria to get up close and personal with our hero. She reels Dimiri in, seduces him, then invites Gemma over, for what rapidly becomes a credible candidate for Most Uncomfortable Dinner Party Ever.

In particular, she aims at his relationship with Gemma Rosselli (Golino), who works in a pastry-shop in the German town Mainz, which Sanin is visiting. He saves the live of her brother, is invited to dinner, and the two fall in love. Which is unfortunate, since she is already engaged. However, when Dmitri shows himself willing to fight a duel to protect Gemma’s honor (even though the incident was actually provoked by Maria), she breaks the relationship off, and Dmitri begins preparing to sell his Russian estates and move permanently to Mainz. He bumps into an old friend, Prince Ippolito Polozov (Forsythe), who says his wife may be interested in purchasing Dmitri’s land – but this is merely a ruse for Maria to get up close and personal with our hero. She reels Dimiri in, seduces him, then invites Gemma over, for what rapidly becomes a credible candidate for Most Uncomfortable Dinner Party Ever.

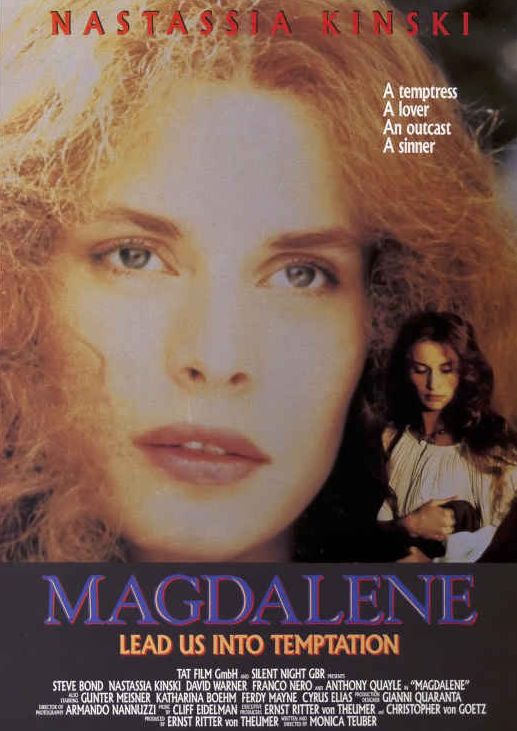

So, the moral of the story is, it’s perfectly alright to drug and abduct a woman that takes your fancy, because if you’re nice to her, she’ll end up falling in love with you – though “Stockholm syndrome” would perhaps seem a more credible explanation. Man, I’d have got laid so much, if only I’d known that in the eighties. Okay: known that,

So, the moral of the story is, it’s perfectly alright to drug and abduct a woman that takes your fancy, because if you’re nice to her, she’ll end up falling in love with you – though “Stockholm syndrome” would perhaps seem a more credible explanation. Man, I’d have got laid so much, if only I’d known that in the eighties. Okay: known that,

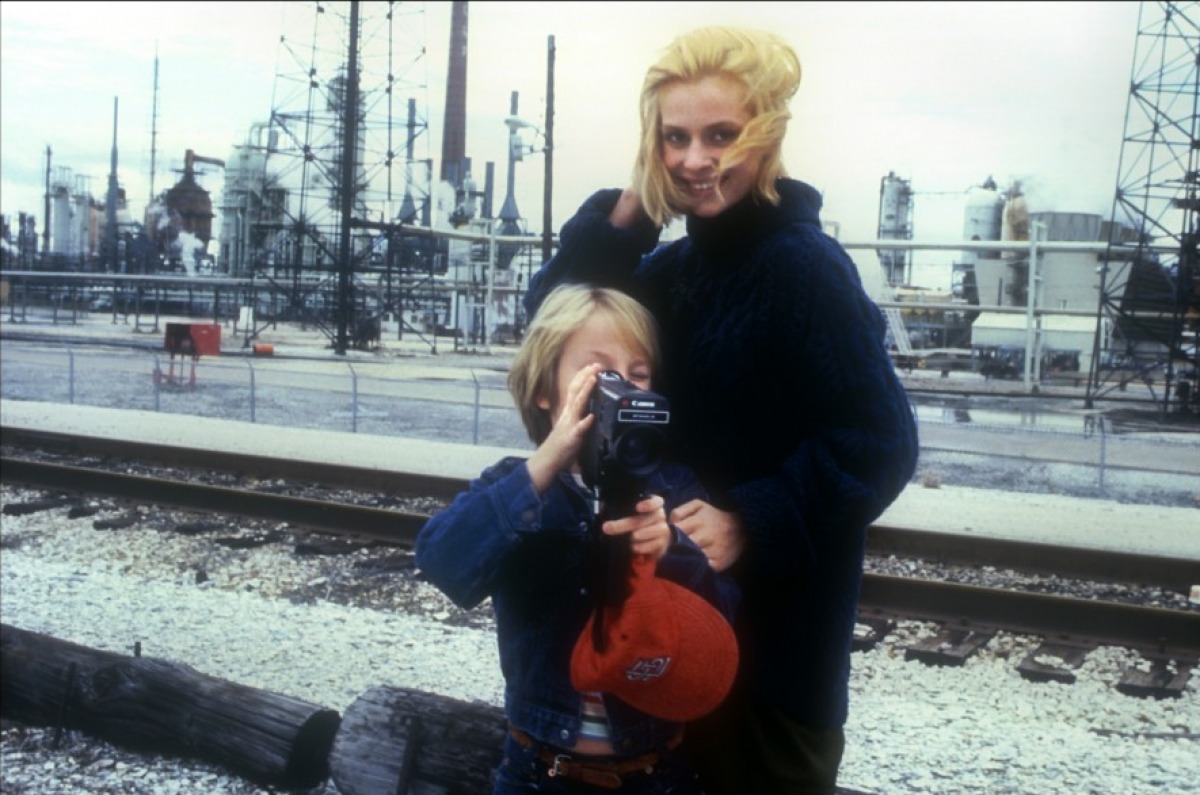

The Cannon Group studio of Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus was not exactly renowned for its art-house output, being better known as home of the Death Wish franchise and no small number of Chuck Norris films. But, for some reason, Golan-Globus also had a good relationship with Konchalovsky, who had been a collaborator with Andrei Tarkovsky, and he directed several films for the company, of which Maria’s Lovers was the first. Indeed, it was Konchalovsky’s first English-language feature, and is a rather lugubrious tale of GI Ivan Bibic (Savage), who returns from war to marry Maria Bosic (Kinski), the woman whose image kept him going through time spent in a Japanese POW camp, only to find himself unable to perform sexually with his new bride. One can only wonder what Charles Bronson would have done in the same situation. It would probably have involved a pool ball in a sock.

The Cannon Group studio of Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus was not exactly renowned for its art-house output, being better known as home of the Death Wish franchise and no small number of Chuck Norris films. But, for some reason, Golan-Globus also had a good relationship with Konchalovsky, who had been a collaborator with Andrei Tarkovsky, and he directed several films for the company, of which Maria’s Lovers was the first. Indeed, it was Konchalovsky’s first English-language feature, and is a rather lugubrious tale of GI Ivan Bibic (Savage), who returns from war to marry Maria Bosic (Kinski), the woman whose image kept him going through time spent in a Japanese POW camp, only to find himself unable to perform sexually with his new bride. One can only wonder what Charles Bronson would have done in the same situation. It would probably have involved a pool ball in a sock. It apparently took four scriptwriters to come up with this nonsense, along with uncredited work by Floyd Byars, according to the IMDb. Beside Konchalovsky, there was Gerard Brach, who was one of the writers on Tess, Paul Zindel and Marjorie David. Quite why it took so many fingers on the typewriter to come up with this, it’s hard to say, because there’s nothing particularly complex or demanding about the storyline, which is not much more than “boy meets girl” stuff. Nor, to be honest, is there much of interest in the plot. What the film does have, fortunately, are a slew of good performances, probably topped by Savage. While the situation in which he finds himself may stretch the viewer’s credulity, there’s no denying the sense of real pain which results. He first achieves the nirvana of marrying his childhood sweetheart, only for things to implode in a welter of guilt, recriminations and sexual paranoia (albeit the last eventually proving fully justified), and you can’t help but feel for the man.

It apparently took four scriptwriters to come up with this nonsense, along with uncredited work by Floyd Byars, according to the IMDb. Beside Konchalovsky, there was Gerard Brach, who was one of the writers on Tess, Paul Zindel and Marjorie David. Quite why it took so many fingers on the typewriter to come up with this, it’s hard to say, because there’s nothing particularly complex or demanding about the storyline, which is not much more than “boy meets girl” stuff. Nor, to be honest, is there much of interest in the plot. What the film does have, fortunately, are a slew of good performances, probably topped by Savage. While the situation in which he finds himself may stretch the viewer’s credulity, there’s no denying the sense of real pain which results. He first achieves the nirvana of marrying his childhood sweetheart, only for things to implode in a welter of guilt, recriminations and sexual paranoia (albeit the last eventually proving fully justified), and you can’t help but feel for the man.