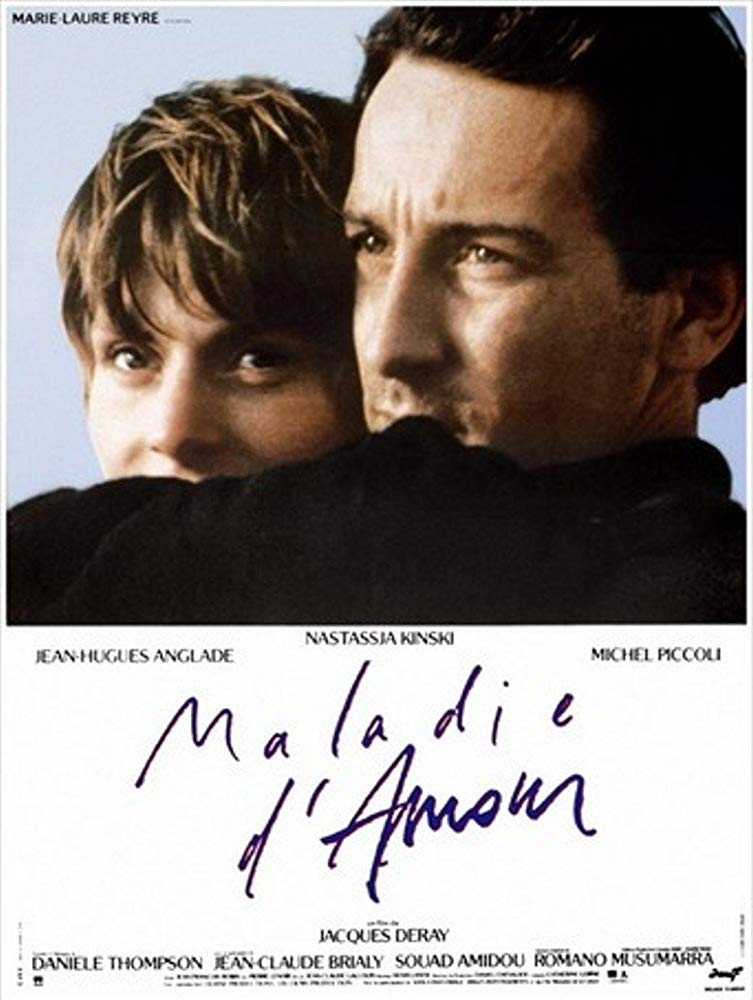

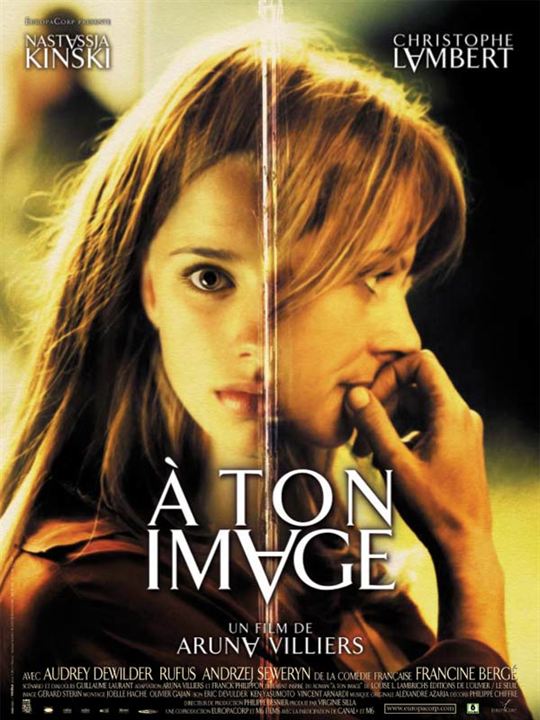

Dir: Jacques Deray

Star: Nastassja Kinski, Jean-Hugues Anglade, Michel Piccoli, Jean-Claude Brialy

In which we learn, that everyone in France is a slut.

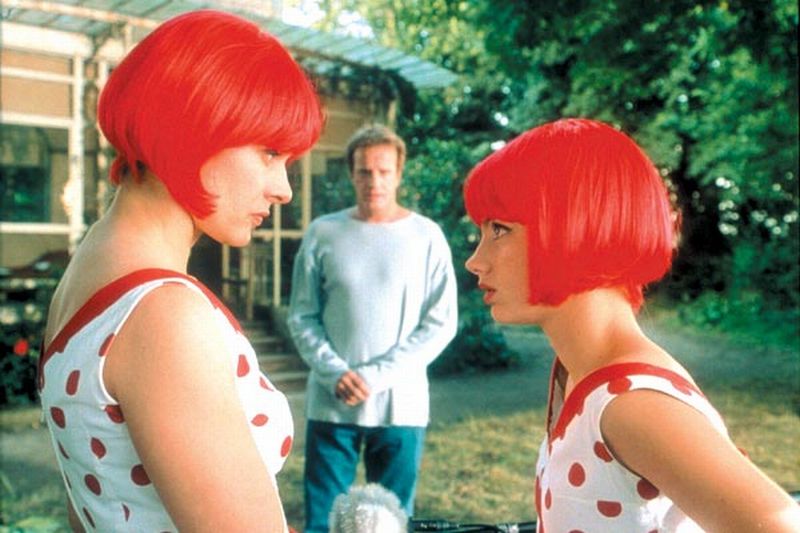

Okay, maybe that’s an exaggeration. But it sure seems like it here: in the love triangle between hairdresser Juliet (Kinski), and doctors Clément (Anglade) and Raoul (Bergeron), fidelity is low on the list of priorities for everyone. Clément has an “almost fiancée,” and Raoul is flat-out married: these existing relationships hardly appear to present the slightest impediment to either man getting involved with Juliet. Meanwhile, she bounces between the two of them like a elaborately coiffed shuttlecock (if, like me, you’d forgotten this was an eighties film, some of her hairstyles will quickly remind you; an example can be seen below), as her whims appear to dictate. It’s like she’s forever requiring a second opinion.

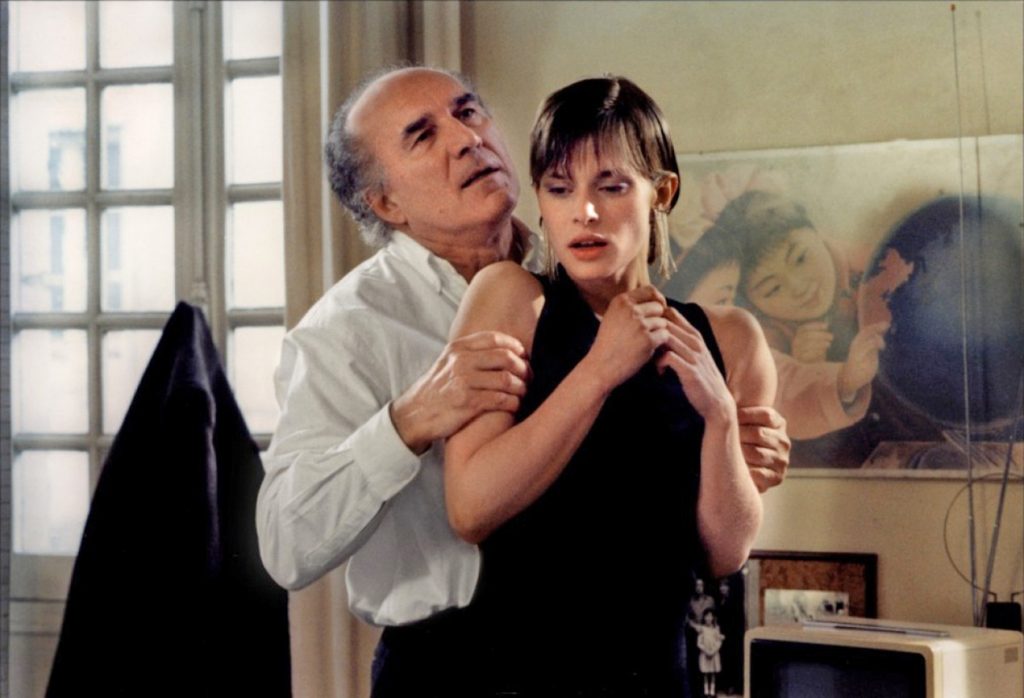

You can argue who has the prior claim. Clément is the first to see her, sharing a carriage and a “strangers on a train” moment on their way in to Bordeaux. But it’s Raoul who is the first to engage with her, being a customer at the salon where Juliet works. However, it isn’t long before the smarts gulf between a highly-respected oncologist and a hairdresser starts to prove problematic. When the pet dog he gives her dies (it belonged to a late patient of his), Raoul isn’t around to comfort her. Clément is, leading to a passionate session, word of which unfortunately, gets back to Raoul. He calls the subordinate doctor into his office and berates him about the deceased canine. “He had a first-class funeral. Two beautiful young undertakers. They fucked on his grave, then went to a hotel.”

Seeing his career evaporating in front of his eyes, Clément backpedals desperately, saying “That didn’t count. It was just playing around… It was nothing,” which counts as a bit of a dick move, I’d say. It is, however, orders of magnitude better than Raoul’s behavior: for he has been tape-recording the conversation, and rushes home to play it to Juliet. She’s not happy with his dismissal, needless to say, and breaks off their affair. However, a little further down the road, she makes up with Clément; he abandons his specialist’s position to avoid reprisals from Raoul, in favor of general practice in a small French town. For a brief while, they appear to be happy. But wouldn’t you know it? She gets bored of life as a provincial housewife, after he wants to have a child, and heads back to Bordeaux, to be with Raoul once again.

Really? I know it’s eighties Kinski and all, but c’mon. There’s a certain point at which any sensible person would have to say: “If you don’t want to be with me, then I don’t want to be with you.” The film’s biggest weakness is its failure to get over to the viewer why both these men – successful professionals, presumably wealthy and not exactly ugly – are so completely obsessed with Juliet. Physical attraction goes only so far, especially in the apparent absence of other qualities. She is clearly not an intellectual foil for them (she names her dog Levi Strauss – not after the philosopher, but for some unexplained reason, the jeans), and displays little or no personality to speak of. If there had been some kind of adversarial relationship established between Raoul and Clément, with Juliet as a trophy, even that would have been an improvement on what the film offers.

Then, just as I’m growing increasingly annoyed by this, the film goes for the nuclear option of cinematic clichés. What else could it be, when a woman is being fought over by a pair of cancer doctors? If you guessed “Juliet gets cancer,” give yourself two points, whenever you’ve finished rolling your eyes. It was cynical emotional manipulation in 1970, when Ali McGraw went down with leukemia, and has become increasingly trite and ineffective since. Here, there’s almost no emotional impact, since the movie has given you little or no reason to care about Juliet, up to that point. The rest of the movie plays out like a Lifetime ‘Disease of the Week’ TVM, except that Raoul is rewarded for his ceaseless efforts to help Juliet find a cure, by her bailing on him, and running back to the provincial doctor’s house.

I started this project back in the summer of 2013, and from the start it was clear Maladie d’Amour was going to be one of those “lost” Kinski films, apparently unavailable with English subtitles. After more than five years, I had given up hope when, just a couple of weeks for before the site officially launched, I discovered someone on one of those grey-market film sites had created a set of fan subs for it. My delight knew no bounds… until I watched what has to be considered one of her weakest efforts of the decade. I’m not sure who deserves blame. The three actors who form the triangle all have solid track records, and Deray has as well. However, the latter is far better known for crime movies and thrillers, with the likes of Alain Delon and Jean-Paul Belmondo. The results here are evidence that crafting a tragic love story requires a different set of cinematic skills altogether.

Equal criticism should probably be directed at the screenwriters, Danièle Thompson and well-known Polish film-maker, Andrzej Żuławski, most famous for directing Possession, starring Isabelle Adjani and Sam Neill. Their script knows where it wants to go, aiming for a poignant ending – it reminded me a little of Tess, in its doomed heroine, taking up residence in an empty house. It just has no clue how to get there, pushing the characters around in the apparent hope of generating a spark to set things ablaze. This film apparently relies on the charisma of its actors to make up the deficit: for whatever reason, that doesn’t happen, with Nastassja delivering one of her most uninterested performances. This one definitely was not worth waiting five years to see.

Remember when cloning was the Next Big Thing? Or course, there have been clone movies around for a long time; 1978’s The Boys From Brazil was probably the first to take the idea mainstream. However, there was a five-year period, roughly covering 2000-04, when they seemed particularly fashionable, including things like The 6th Day. What almost every clone film, regardless of era, seems to have in common is their cautionary nature. Whether it’s Multiplicity or Godsend, cloning is rarely if ever depicted as a boon to humanity. Stuff goes wrong, because this is, it appears, firmly filed in the box marked “things with which mankind is not supposed to meddle.” And so it proves here, inevitably.

Remember when cloning was the Next Big Thing? Or course, there have been clone movies around for a long time; 1978’s The Boys From Brazil was probably the first to take the idea mainstream. However, there was a five-year period, roughly covering 2000-04, when they seemed particularly fashionable, including things like The 6th Day. What almost every clone film, regardless of era, seems to have in common is their cautionary nature. Whether it’s Multiplicity or Godsend, cloning is rarely if ever depicted as a boon to humanity. Stuff goes wrong, because this is, it appears, firmly filed in the box marked “things with which mankind is not supposed to meddle.” And so it proves here, inevitably.