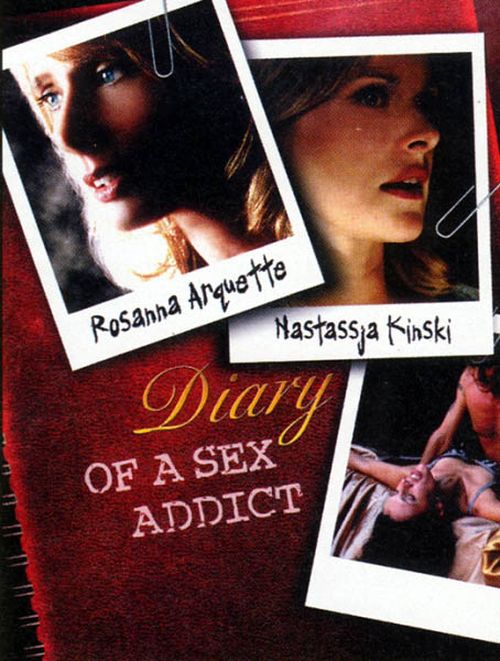

Dir: Joseph Brutsman

Star: Michael Des Barres, Rosanna Arquette, Nastassja Kinski, Eva Jenícková

Beyond one of the most click-baity titles in cinematic history, lurks something slightly more than the soft-porn bonkathon which it would appear to be, and is instead trying to offer a psychological portrait of the titular character. This is the not-exactly subtly named Sammy Horn (Des Barres), a restaurant owner bearing some resemblance to a certain celebrity chef whose name might rhyme with Bordon Hamsay, sharing similar hair and a quick temper. Project Kinski legal advisers counsel me to stress that is all they have in common.

Horn has a lovely wife, Grace (Arquette), and a charming young child, but this does not stop in the slightest from trying to bed every woman to cross his path. That list includes workers in his restaurant, women he meets in bars, his doctor’s receptionist, hookers he hires, strip-club bartenders, even Grace’s sister is fair game for Sammy’s lust. This all causes no end of problems: he gets arrested after a particularly vocal sex session in the bathroom of a restaurant, and has a scary moment when his doctor tells him Grace is HIV-positive. The lies and deceit he’s forced into with his wife don’t help, and in the end he realizes he has a problem and seeks help.

That comes in the form of therapist Dr. Jane Bordeaux (Kinski), to whom he details his recent exploits, as she listens and frowns – I guess she’s trying to establish a motive and figure out how Horn can control his urges. While I didn’t notice at the time, it strikes me as not exactly much of a stretch to find a parallel between Sammy and Nastassja’s father, Klaus, whose fleshly appetites were the stuff of legend (at least, in his self-penned memories – who can say how close these came to the reality?). Perhaps playing a therapist was a coping mechanism of some kind for the daughter? Hey, it’s not much more dubious than the psychology this has to offer, and would at least explain Kinski’s presence. Now, if only we could find a similar excuse for Arquette…

It is, certainly, a title likely to mislead, especially since the two lead actresses remain more or less completely attached to their clothes. There’s no shortage of sex, to be sure, but it’s not by anyone of whom you’ll ever have heard. It’s also a bit of a time-capsule, offering a glimpse of an era when aggressive sexual behavior was rather more acceptable. From a 2016 viewpoint, Horn comes over as predatory, at the very least – arguably even, to borrow a quote from Cersei Lannister, “a bit of a rapist”, since gaining consent hardly seems to be on his to-do list before grabbing on to his next target. You could also make the case he abuses his power, such as with a sous chef at his restaurant. But Horn is not actually an unsympathetic character, and Des Barres’s portrayal gives a bit more depth to him than you’d expected.

It is, certainly, a title likely to mislead, especially since the two lead actresses remain more or less completely attached to their clothes. There’s no shortage of sex, to be sure, but it’s not by anyone of whom you’ll ever have heard. It’s also a bit of a time-capsule, offering a glimpse of an era when aggressive sexual behavior was rather more acceptable. From a 2016 viewpoint, Horn comes over as predatory, at the very least – arguably even, to borrow a quote from Cersei Lannister, “a bit of a rapist”, since gaining consent hardly seems to be on his to-do list before grabbing on to his next target. You could also make the case he abuses his power, such as with a sous chef at his restaurant. But Horn is not actually an unsympathetic character, and Des Barres’s portrayal gives a bit more depth to him than you’d expected.

There is an odd subplot, which seems to be trying to enhance the positive side. Horn is taking his family to the movies, and gets in an altercation with the ticket-taker, that ends with the latter being fired. The now-unemployed man starts stalking Horn, with bad intentions, but a confrontation in an alley behind the restaurant ends in Horn offering his assailant a job – albeit with a warning to keep his temper in check. I was expecting something more to follow, yet nothing ever comes of this thereafter. It’s oddly affecting, perhaps a result of it being one of the few scenes where Horn is actually communicating with another human being, rather than trying to get into their pants.

Even the sequences between him and Dr. Bordeaux don’t possess much in the way of apparent honesty: as therapists go, she doesn’t seem particularly interested in locating the cause of his addiction, or offering any kind of significant treatment. Well, unless “staring disapprovingly” is what passes for mental health care these days. It’s certainly an easy enough role for Kinski, who only appears in a single location (her office) and likely dashed off her entire performance in less than a week. To be honest, it’s more of a backdrop to allow for the film’s main purpose, which appears to be wish fulfillment for middle-aged men: Horn is not exactly a hunk, yet still appears to be capable of getting any woman (save Dr. Bordeaux) onto his genitals, in the time it takes the rest of us to boil an egg.

What’s a little odd though, is the relatively restrained nature of the sex scenes, which, if enthusiastic (to the point where I felt compelled to lower the volume!), contain a much higher amount of clothing then I was expecting. It’s still certainly not a family film, but if you are expecting the soft-core bonkathon mentioned earlier, you’re going to end up disappointed, even if every woman in it, is more or less uniformly attractive. As such, it seems almost to possess a split personality: partly wanting to be a serious drama about addiction, yet clothed in the trappings of a late-night cable television movie. Probably inevitably, it manages to fall short on both fronts.

That all said, I didn’t hate this as much as many reviews I’ve read. It would be easy for a film on the topic to take a hypocritical approach, both condemning the protagonist’s behavior, while salaciously exploiting it, yet that doesn’t seem to happen here. For all the storyline flaws, Des Barres’s portrayal of Horn is a surprisingly effective one. He’s a bundle of contradictory feelings, behavior and traits – if not consistent, by any stretch, it may well be a more accurate portrayal of most people’s frailties and failings than many Hollywood creations.

But Leslie also seems to be completely elusive, and even the private detective Susan hires is, at least initially, unable to make progress, as the address Kevin had for Leslie appears to be a complete dead end, with nobody knowing her there. Is Kevin telling the truth? If not, who is behind it all? Potential candidates include Peggy, as well as Justine, Susan’s younger sister; the two have a strained relationship, because by the terms of their parents’ will, Susan controls the trust fund income Justine gets. That’s a direct result of Justine’s husband being a low-life slimeball with some bad, money-burning habits, so perhaps he’s involved too? You won’t find out the truth until right at the end and… Well, I can’t honestly say I was particularly convinced by the resolution. I guess, in some ways, it “makes sense”, as long as you have a fairly loose definition of what constitutes sense.

But Leslie also seems to be completely elusive, and even the private detective Susan hires is, at least initially, unable to make progress, as the address Kevin had for Leslie appears to be a complete dead end, with nobody knowing her there. Is Kevin telling the truth? If not, who is behind it all? Potential candidates include Peggy, as well as Justine, Susan’s younger sister; the two have a strained relationship, because by the terms of their parents’ will, Susan controls the trust fund income Justine gets. That’s a direct result of Justine’s husband being a low-life slimeball with some bad, money-burning habits, so perhaps he’s involved too? You won’t find out the truth until right at the end and… Well, I can’t honestly say I was particularly convinced by the resolution. I guess, in some ways, it “makes sense”, as long as you have a fairly loose definition of what constitutes sense.

There’s certainly a loose grip of nationality present here, even past the shift of the entire story from Wessex to Old West. Bentley, born in Arkansas, plays a Scot, while an actual Scot, Mullan, portrays an Irishman. Meanwhile, the Ukrainian Jovovich is inexplicably a Portuguese character, which makes Kinski’s geographical shift from Germany to Poland seem relatively trivial. Most are fine, though being so used to seeing Milla kicking zombie ass, it takes a bit of adjustment to seeing her in a petticoat, playing the owner/madam of the town’s saloon/brothel. For Kinski, of course, this is not her first time at the “tragic heroine in a Hardy novel” rodeo – I note that Winterbottom also did Jude a few years earlier – and she looks suitably wan as she slowly fades away to – and I trust I’m not spoiling this for anyone – her eventual demise. It doesn’t appear to be an enormous stretch for her talents, and I can imagine the director passing her acting notes such as “Look iller”.

There’s certainly a loose grip of nationality present here, even past the shift of the entire story from Wessex to Old West. Bentley, born in Arkansas, plays a Scot, while an actual Scot, Mullan, portrays an Irishman. Meanwhile, the Ukrainian Jovovich is inexplicably a Portuguese character, which makes Kinski’s geographical shift from Germany to Poland seem relatively trivial. Most are fine, though being so used to seeing Milla kicking zombie ass, it takes a bit of adjustment to seeing her in a petticoat, playing the owner/madam of the town’s saloon/brothel. For Kinski, of course, this is not her first time at the “tragic heroine in a Hardy novel” rodeo – I note that Winterbottom also did Jude a few years earlier – and she looks suitably wan as she slowly fades away to – and I trust I’m not spoiling this for anyone – her eventual demise. It doesn’t appear to be an enormous stretch for her talents, and I can imagine the director passing her acting notes such as “Look iller”.

Director Battersby has been responsible for five feature films – all of which also had scripts written by Battersby. This is probably a warning in itself; at least Quentin Tarantino can get other people to make his scripts occasionally – and the results are often the better for it, as we see in True Romance and From Dusk Till Dawn. Director Battersby really needed to have a stern talk with writer Battersby, and send the script back to himself with some strongly-worded rewrite instructions, because the further this drifts on, the more disconnected and implausible it becomes. There appears to be a stunning ignorance for how the law actually works, for example: cops do not casually give suspects 48 hours to solve cases, and federal charges for helping someone escape from custody do not magically evaporate, just because they were wrongly convicted.

Director Battersby has been responsible for five feature films – all of which also had scripts written by Battersby. This is probably a warning in itself; at least Quentin Tarantino can get other people to make his scripts occasionally – and the results are often the better for it, as we see in True Romance and From Dusk Till Dawn. Director Battersby really needed to have a stern talk with writer Battersby, and send the script back to himself with some strongly-worded rewrite instructions, because the further this drifts on, the more disconnected and implausible it becomes. There appears to be a stunning ignorance for how the law actually works, for example: cops do not casually give suspects 48 hours to solve cases, and federal charges for helping someone escape from custody do not magically evaporate, just because they were wrongly convicted.

James uses his imagination as an outlet from the rough world which he inhabits, such as riffing off an ancestor – the Marciano of the title – who was a diplomat, but is elevated to the King of Italy in the boy’s mind! Though this also takes him down some dark paths, most notably, the sequence where he fantasizes about shooting Curt with the gun he finds in his mother’s drawer. [As an aside: mental illness and firearms are never a good combination…] I’d perhaps like to have seen that aspect drawn out and explored more, not least because James has a good deal from which to escape. His generally upbeat and optimistic nature is in stark contrast to the intensely bipolar personality of Katie, who can flick from loving mother to scary, scary person in an instant. Mind you, her history – not least with regard to her son – appears to be a sad saga in itself, and she’s never other than someone for whom you feel sympathetic.

James uses his imagination as an outlet from the rough world which he inhabits, such as riffing off an ancestor – the Marciano of the title – who was a diplomat, but is elevated to the King of Italy in the boy’s mind! Though this also takes him down some dark paths, most notably, the sequence where he fantasizes about shooting Curt with the gun he finds in his mother’s drawer. [As an aside: mental illness and firearms are never a good combination…] I’d perhaps like to have seen that aspect drawn out and explored more, not least because James has a good deal from which to escape. His generally upbeat and optimistic nature is in stark contrast to the intensely bipolar personality of Katie, who can flick from loving mother to scary, scary person in an instant. Mind you, her history – not least with regard to her son – appears to be a sad saga in itself, and she’s never other than someone for whom you feel sympathetic.