Harem (1985) gallery

Gallery

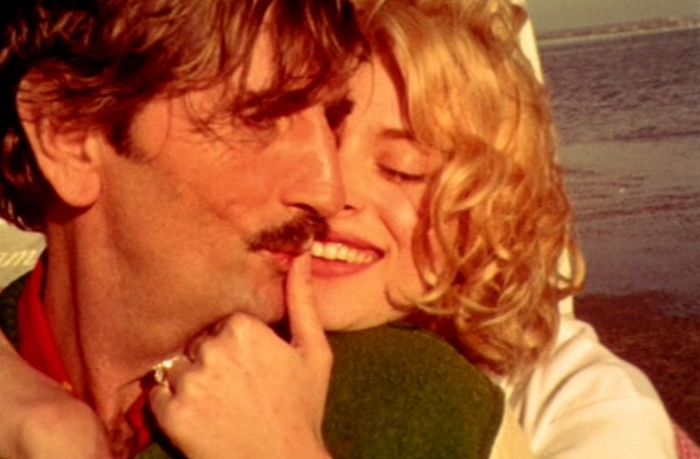

Maria’s Lovers (1984)

Dir: Andrei Konchalovsky

Star: John Savage, Nastassja Kinski, Keith Carradine, Robert Mitchum

“When I came to Hollywood, no one knew me, basically, except for Kinski. She was just coming up as [a] star, and she asked me if I would do something with her. I had this script which I had planned to make in Europe with [Isabelle] Adjani. Kinski was hot, so I got some clout, and finally Menahem Golan said, “Set the story in America and we will do it.” But I thought it would not be right in truly American society, these characters, too emotional, so I put it in a Yugoslav enclave.”

— Andrei Konchalovsky, quoted in Baby I Don’t Care, by Lee Server

The Cannon Group studio of Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus was not exactly renowned for its art-house output, being better known as home of the Death Wish franchise and no small number of Chuck Norris films. But, for some reason, Golan-Globus also had a good relationship with Konchalovsky, who had been a collaborator with Andrei Tarkovsky, and he directed several films for the company, of which Maria’s Lovers was the first. Indeed, it was Konchalovsky’s first English-language feature, and is a rather lugubrious tale of GI Ivan Bibic (Savage), who returns from war to marry Maria Bosic (Kinski), the woman whose image kept him going through time spent in a Japanese POW camp, only to find himself unable to perform sexually with his new bride. One can only wonder what Charles Bronson would have done in the same situation. It would probably have involved a pool ball in a sock.

The Cannon Group studio of Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus was not exactly renowned for its art-house output, being better known as home of the Death Wish franchise and no small number of Chuck Norris films. But, for some reason, Golan-Globus also had a good relationship with Konchalovsky, who had been a collaborator with Andrei Tarkovsky, and he directed several films for the company, of which Maria’s Lovers was the first. Indeed, it was Konchalovsky’s first English-language feature, and is a rather lugubrious tale of GI Ivan Bibic (Savage), who returns from war to marry Maria Bosic (Kinski), the woman whose image kept him going through time spent in a Japanese POW camp, only to find himself unable to perform sexually with his new bride. One can only wonder what Charles Bronson would have done in the same situation. It would probably have involved a pool ball in a sock.

Of course, we are dealing with a profound implausibility at the very core of the movie: that a virginal Nastassja Kinski causes erectile dysfunction. Yeah. I’m finding myself struggling with that concept a bit, and wonder if casting a slightly-less attractive actress might have helped with the disbelief. Admittedly, part of the point is that it’s Ivan’s idealized image of Maria which is the problem, coupled with his apparent case of PTSD, back when it was still called “shell shock.” The film opens with clips from John Huston’s documentary, Let There be Light, showing interviews with returning veterans, on to which Ivan’s presence has been tacked, and his sleep is peppered with nightmares – the most ludicrous of which sees Savage cramming half a fake rat into his mouth. Still, it’s a fairly specific disorder in its symptoms, Ivan both apparently functioning better than many vets, and also having no issues with other women, judging by an early fling with a family friend.

But he marries Maria, despite his father (Mitchum, filling in for an unwell Burt Lancaster) believing her to be “too good for him,” and that’s when everything starts to fall apart, as the stress of his problem grinds incessantly on the newlyweds. Not helping matters is the presence of her former boyfriend (Vincent Spano), who still carries a torch for Maria, or the arrival of an itinerant musician, Clarence Butts (Carradine), who can apparently cause pantie-wetting with the drop of a minor chord. After Maria has experimented with self-pleasuring, it’s Clarence who seduces her, though apparently racked by guilt, she tosses him out of the house immediately. Not soon enough, however, for the pregnancy which results, though Ivan is now off working in a hellhole slaughterhouse (alongside a very young John Goodman). After an uncomfortable encounter with his heavily-pregnant wife, Ivan’s dying father makes an emotional plea for them to reunite. And, hey, it turns out that knowing Maria was no longer an untouchable goddess was all Ivan needed to get it up. Who knew?

It apparently took four scriptwriters to come up with this nonsense, along with uncredited work by Floyd Byars, according to the IMDb. Beside Konchalovsky, there was Gerard Brach, who was one of the writers on Tess, Paul Zindel and Marjorie David. Quite why it took so many fingers on the typewriter to come up with this, it’s hard to say, because there’s nothing particularly complex or demanding about the storyline, which is not much more than “boy meets girl” stuff. Nor, to be honest, is there much of interest in the plot. What the film does have, fortunately, are a slew of good performances, probably topped by Savage. While the situation in which he finds himself may stretch the viewer’s credulity, there’s no denying the sense of real pain which results. He first achieves the nirvana of marrying his childhood sweetheart, only for things to implode in a welter of guilt, recriminations and sexual paranoia (albeit the last eventually proving fully justified), and you can’t help but feel for the man.

It apparently took four scriptwriters to come up with this nonsense, along with uncredited work by Floyd Byars, according to the IMDb. Beside Konchalovsky, there was Gerard Brach, who was one of the writers on Tess, Paul Zindel and Marjorie David. Quite why it took so many fingers on the typewriter to come up with this, it’s hard to say, because there’s nothing particularly complex or demanding about the storyline, which is not much more than “boy meets girl” stuff. Nor, to be honest, is there much of interest in the plot. What the film does have, fortunately, are a slew of good performances, probably topped by Savage. While the situation in which he finds himself may stretch the viewer’s credulity, there’s no denying the sense of real pain which results. He first achieves the nirvana of marrying his childhood sweetheart, only for things to implode in a welter of guilt, recriminations and sexual paranoia (albeit the last eventually proving fully justified), and you can’t help but feel for the man.

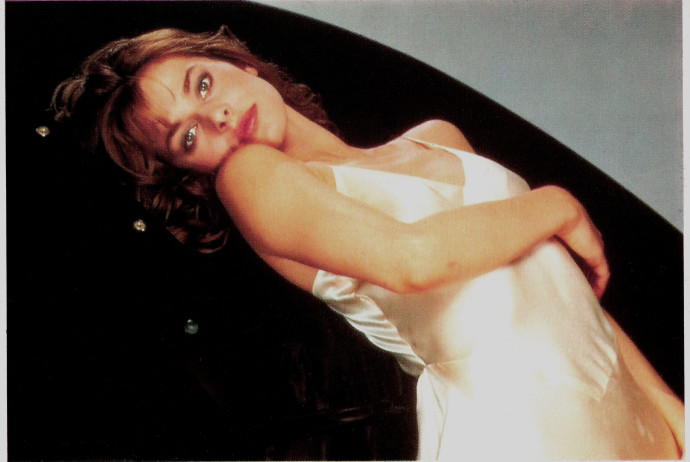

The other performances are somewhat less memorable, largely because they’re more restrained, probably for the best. It’s nice to see, for the first time in a while, Kinski paired with a man of her own age – or, at least, relatively so, Savage still being her elder by more than a decade, though he plays younger than that. She does capture the wild-eyed innocence of youth nicely, and it’s hard to resist the imagery of a stocking-clad Nastassja, writhing around on the bed like a serpent. That’s appropriate, since here she is like Eve, whose quest for forbidden knowledge brought about her expulsion from paradise, along with her husband. I dunno. I may be stretching a bit here, visions of Richard Avedon photos bubbling around my subconscious. There may also be an element of art imitating life here: according to Konchalovsky, Kinski was having a love affair during shooting with Spano “and she had a baby from that.” Which must come as a surprise to the baby’s acknowledged father, Ibrahim Moussa, though he was rumored at the time to be responsible.

There’s no denying that Konchalovsky brings a distinctly European feel to what is a very blue-collar American location, Brownsville, Pennsylvania [the house used in the film is still standing there, albeit in rundown condition]. It’s certainly easy to see how it was originally conceived as an Old World film, and the attempt to shoe-horn it into American culture can’t be described as enormously successful. However, it does just about skate past, on the strength of some good performances and effective period atmosphere.

Maria’s Lovers (1984) gallery

Gallery

Paris, Texas (1984) gallery

Gallery

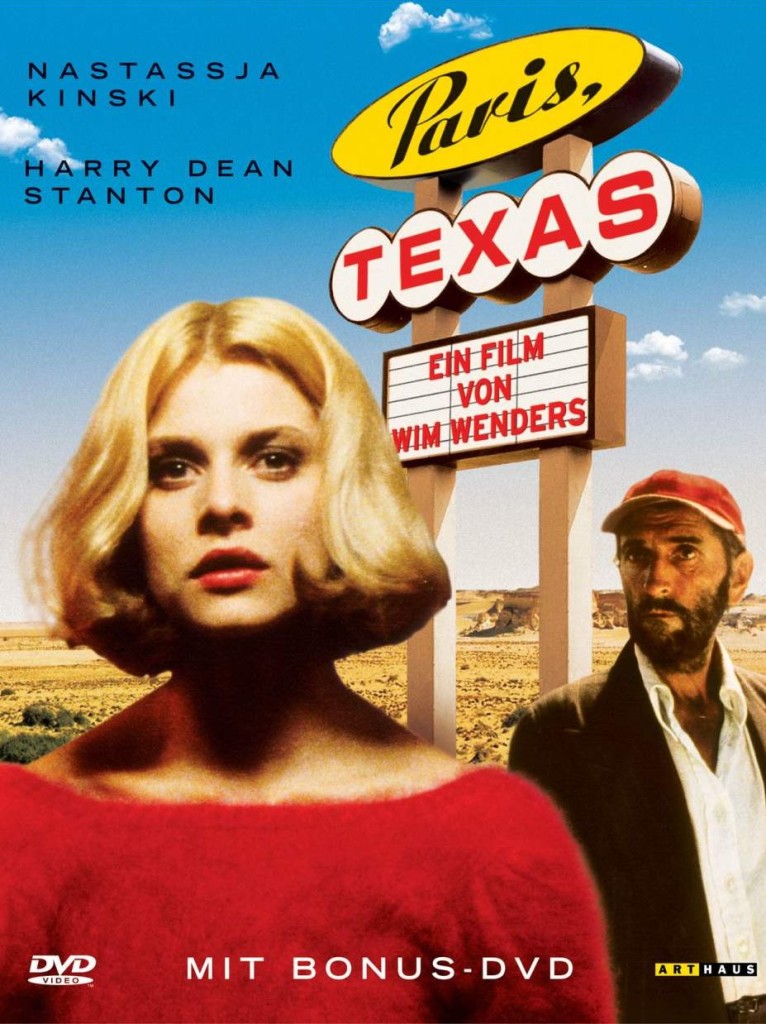

Paris, Texas (1984)

Dir: Wim Wenders

Star: Harry Dean Stanton, Dean Stockwell, Hunter Carson, Nastassja Kinski

The first time I saw this was, approximately, 1985. At the time, I was a student at Aberdeen University in Scotland, and had not even been to America at that stage. Now, I’ve been living in Phoenix for more than 13 years, which is somewhere in the middle of the two main locations depicted by Wenders – Houston and Los Angeles – and contains elements of both. This may help explain why I appreciated the setting rather more now, Wenders bringing a fresh, European eye to the landscape in which this European is now located, and depicting how the quest for the American dream can turn in to the American nightmare. Even little things, like a scene set at the Cabazon dinosaur roadside attraction, later made famous in PeeWee’s Big Adventure, demonstrate the director’s eye for the different.

The first time I saw this was, approximately, 1985. At the time, I was a student at Aberdeen University in Scotland, and had not even been to America at that stage. Now, I’ve been living in Phoenix for more than 13 years, which is somewhere in the middle of the two main locations depicted by Wenders – Houston and Los Angeles – and contains elements of both. This may help explain why I appreciated the setting rather more now, Wenders bringing a fresh, European eye to the landscape in which this European is now located, and depicting how the quest for the American dream can turn in to the American nightmare. Even little things, like a scene set at the Cabazon dinosaur roadside attraction, later made famous in PeeWee’s Big Adventure, demonstrate the director’s eye for the different.

Travis Henderson (Stanton) staggers out of the desert and collapses. He’s carrying a business card belong to his brother, Walt (Stockwell), who travels from his Los Angeles home to collect Travis, despite his ongoing effort to keep walking, heading to an initially unknown destination, later revealed to be the city of Paris, Texas, where Travis has a vacant lot. Initially, he won’t even speak to his brother, but as the pair drive back to LA – Travis refusing to fly – he opens up, at least somewhat, though the question of where he has been for the past four years, remains unanswered. He disappeared after he and his wife, Jane (Kinski), had split up, leaving their son, Hunter (Carson), who barely remembers his father, for Walt and his wife Anne (Aurore Clement) to take care of.

Slowly, Travis reconnects with his son, and tries to remember what it’s like to be a “good father.” Anne reveals to Travis that Jane got her to set up an account for Hunter, and has been depositing money in it on the same day every month, from a bank in Houston. Driven by his new-found sense of paternal responsibility, Travis sweeps up Hunter and drives half-way across the country to stake out the bank, and wait for Jane to arrive. They almost miss her, but are able to trail her to the dubious establishment where she now works, setting up an incendiary and bitter-sweet reunion – or confrontation, it’s hard to be sure.

Having been thoroughly unimpressed with Falsche Bewegung, I wasn’t sure I’d be able to sit through the near-140 minute running time here, but it proved more a pleasure than a chore. The main reason is Stanton, who delivers a wonderful and touching performance, taking a tragic and deeply-flawed figure, and imbuing him with almost heroic qualities of self-sacrifice and dogged perseverance. Stockwell, too, does a very nice job as the dutiful brother: let’s face it, if a sibling dumped a four-year-old on my doorstep, the first call would be to Child Protective Services! Walt certainly goes above and beyond, and it’s a shame he is entirely forgotten for the second half of the film, as the scenes of the brothers’ road-trip were perhaps the ones I liked best, even if not possessing the emotional punch of those between Stanton and Kinski.

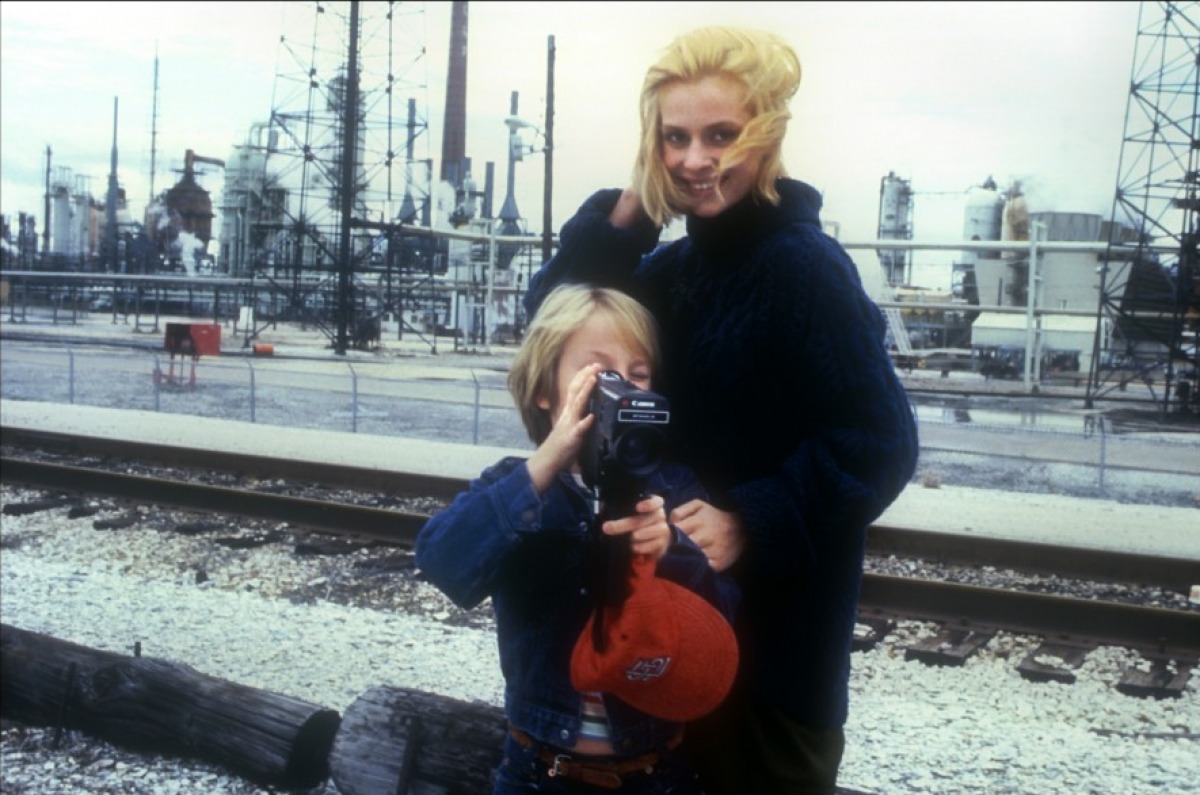

Kinski’s role is an odd one: she’s clearly pivotal to the drama, yet you’re a long way in to the film before she makes her first “live” appearance, discounting her scenes in old vacation footage watched by Travis, Hunter, Walt and Anne. Still, her radiant presence there (right) harks back to an earlier time, when she and her husband were genuinely happy. It’s perhaps seeing this which stars Travis on his doomed – perhaps emotionally suicidal – quest for redemption and to be reunited with Jane. But it’s the scenes where they face each other, separated by one-way glass, that pack the real wallop, laying their souls bare to one another, in a way they were unable to when they were actually together. Shot in long, unflinching takes by Wenders, it’s uncomfortable viewing, due to the raw intensity of the feelings being expressed.

Kinski’s role is an odd one: she’s clearly pivotal to the drama, yet you’re a long way in to the film before she makes her first “live” appearance, discounting her scenes in old vacation footage watched by Travis, Hunter, Walt and Anne. Still, her radiant presence there (right) harks back to an earlier time, when she and her husband were genuinely happy. It’s perhaps seeing this which stars Travis on his doomed – perhaps emotionally suicidal – quest for redemption and to be reunited with Jane. But it’s the scenes where they face each other, separated by one-way glass, that pack the real wallop, laying their souls bare to one another, in a way they were unable to when they were actually together. Shot in long, unflinching takes by Wenders, it’s uncomfortable viewing, due to the raw intensity of the feelings being expressed.

Two aspects on the technical side must be mentioned, because they are absolutely integral to the film’s success. The first is cinematographer Robby Müller, who gives the landscape of tarmac and power-lines an almost mystical feel, turning everyday objects into a magical land, which Travis occupies, rather than living in. The other is Ry Cooder’s soundtrack, which almost becomes a character in its own right, and is based on Blind Willie Johnson’s Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground – interesting to note that Wenders would go on to make The Soul of a Man in 2003, a documentary film focusing on Johnson. Here, Cooder’s score does a magnificent job of capturing the loneliness of the long-distance walker that is Travis.

Finally, L.M. Kit Carson, the father of Hunter, took on the task of beating Sam Shepard’s work into shape, after filming had already started. According to Carson, the set-up in place when he took over was radically different:

[Wim] says, “I set up a great mystery at the beginning of this film, and then I explain it.” I said, “Okay, what are you talking about?” So he told me the two scripts that he had from Sam. One was a script where Nastassja [Kinski’s] father was a big Texas oilman like J.R., and he sent his goons, and they beat up Harry Dean [Stanton] and took her and put her in a penthouse in Houston. And the other version of the script was Nastassja’s mother was under the spell of a televangelist, who of course, in the great tradition, ran whorehouses and drug dens. So he sent his goons to beat up Harry Dean, and took Nastassja and put her in a whorehouse. Those are two versions, and how they separate, and how Hunter ended up living with his brother.

I can’t help wondering what might have happened had Wenders filmed those original versions offered up by Shepard. Still, as is, it remains a genuine classic, and if it’s not top of my personal list, you can certainly see why it’s the highest-rated Kinski film on the IMDb. If anyone ever tries to claim Kinski can’t act, this should be Exhibit A in your counter-argument.

The Hotel New Hampshire (1984)

Dir: Tony Richardson

Star: Jodie Foster, Rob Lowe, Beau Bridges, Nastassja Kinski

“Ms. Kinski’s bear costumes by Richard Tautkus.” That is, I feel fairly confident in saying, a unique credit in cinematic history. However, I can’t say I was too impressed by a film which seems largely like a Hollywood liberal’s wet-dream, nodding its head at the entire gamut of sexual relations, from inter-racial through homosexual to incest. Except rape. For some reason, they draw the line there. I’m still not sure of the era in which the body of the film is supposed to take place. It appears the early stages, where Win Berry (Bridges) marries Mary, are set before the war, which would make the main section, with the oldest kids in high school… the late fifties or early sixties? Maybe the novel is clearer, but otherwise, it seems a much-more tolerant era than I’d heard.

“Ms. Kinski’s bear costumes by Richard Tautkus.” That is, I feel fairly confident in saying, a unique credit in cinematic history. However, I can’t say I was too impressed by a film which seems largely like a Hollywood liberal’s wet-dream, nodding its head at the entire gamut of sexual relations, from inter-racial through homosexual to incest. Except rape. For some reason, they draw the line there. I’m still not sure of the era in which the body of the film is supposed to take place. It appears the early stages, where Win Berry (Bridges) marries Mary, are set before the war, which would make the main section, with the oldest kids in high school… the late fifties or early sixties? Maybe the novel is clearer, but otherwise, it seems a much-more tolerant era than I’d heard.

The focus is on the Berry family and their five kids, mostly on Franny (Foster) and John (Lowe), and the saga as they open one hotel in New England, move to Vienna to open another, then come back to fame and fortune. They go through a series of, frankly, largely implausible escapades, involving everything from terrorists to air-crashes. Irving’s style is often described as “Dickensian,” but I was always much more of a Wilkie Collins fan myself (The Woman in White FTW, bitches!), so you probably have a better handle on what that means than I do. The Berrys seem intent on putting the “fun” in “dysfunctional”; the parents are likely the most well-adjusted, but where’s the interest in a normal, married couple? Hell, even the family dog is affected with perpetual flatulence – oh, hold my aching sides, for this is great literature! The film seems most fascinated by the bundle of neuroses which is Franny, along with her brother, who narrates the movie, and has an interest in his sister which would, under just about any other circumstance, be deemed entirely unhealthy.

What stops it from being entirely unwatchable is the quality of the acting, which is genuinely impressive and turns these (often sex-obsessed) caricatures into something approaching human beings. Even toward the bottom of the cast, there are a lot of people who would go on to achieve fame down the road: Matthew Modine, Joely Richardson, Amanda Plummer, and even a very young Seth Green, as the youngest of the Berry kids. Foster and, perhaps surprisingly, Lowe are both extremely good in their roles, but there is hardly a performance which doesn’t ring truer than the ridiculous characters they’ve been given by the script. Full disclaimer: I haven’t read any Irving, and on the basis of this, won’t exactly be rushing to do so. But I suspect director Richardson may have been too true to the source material, and one senses trimming some of the excess elements might have made for a less over-stuffed movie as an end product. Instead, it seems to tire of some characters and discard them, throwing new ones at the screen instead, before eventually growing bored with them too.

Kinski’s would be a case in point. She doesn’t appear until almost an hour in, playing “Suzie the Bear,” and some backstory is likely necessary first. Early on, we meet Freud, a Jewish entertainer who travels round giving shows with his trained bear. He heads back to Europe, leaving his bear in Win’s custody, but is responsible for bringing the Berrys to Vienna, where he is now blind (blame the Nazis!), and needs help running a hotel. He now has Suzie, an irritable young woman who is convinced she is ugly – pardon me if I give that the snort of derision it richly deserves – and, to avoid having to deal with other humans, spends her life dressed in a bear-suit. Yeah, in other words: the sort of bullshit act only characters in questionable novels actually get to pull off. She’s the focus for a small chunk, forming a brief lesbian relationship with Franny – though their scene in bed is shot so murkily as to be pointless – then heads off to one side, joining the pile of discards in the background. I was, however, taken by the similarity between this and Unfaithfully Yours, both of which have Kinski taking off an animal mask:

Unfaithfully Yours Unfaithfully Yours |

The Hotel New Hampshire The Hotel New Hampshire |

I find these kinda hypnotic, and am sure that any furry Kinski fetishists will be in raptures for most of her scenes. Not being one myself, I was rather more luke-warm – though as should be clear by this point, that applies to the entire endeavor, rather than just her character. I’ll confess I did keep watching, somewhat engrossed to see what lunacy would be thrown at the screen next, which I guess is the basic tenet of story-telling. That, the acting and Jacques Offenbach’s hummable tunes on the soundtrack were just about enough to make for a palatable hour and three-quarters, though I was also reminded of why this made little or no long-term impression, the first time I saw it, almost 20 years previously.

Here’s the trailer. It doesn’t have much Kinski in it – and most of what there is, is in the bear suit. However, it does actually do a fairly good job at capturing the insanity of what unfolds. Personally, if I want to watch dysfunctional families, I’ll have rather more fun with a marathon of Jerry Springer episodes.

The Hotel New Hampshire (1984) gallery

Gallery

Unfaithfully Yours (1984) gallery

Gallery

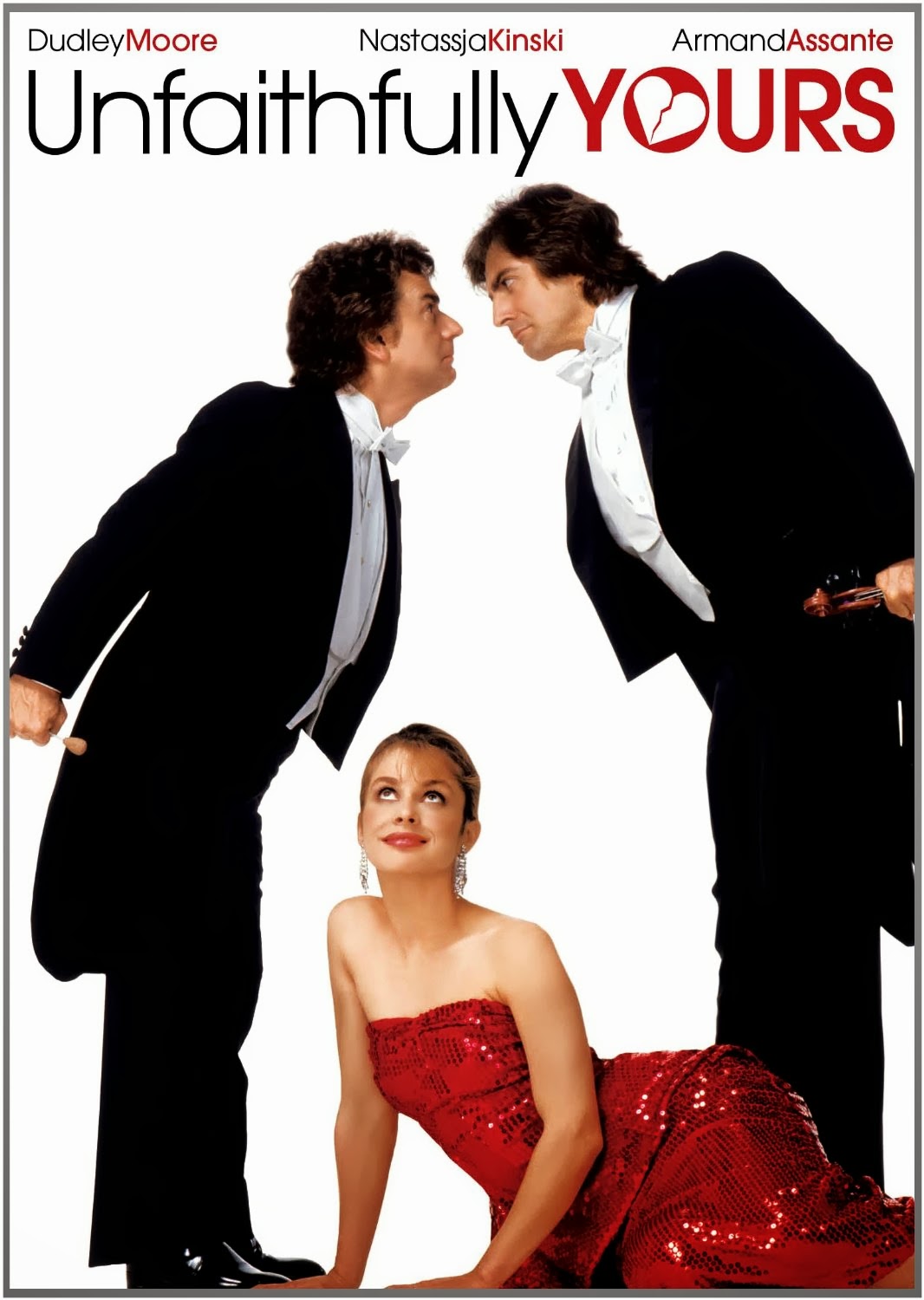

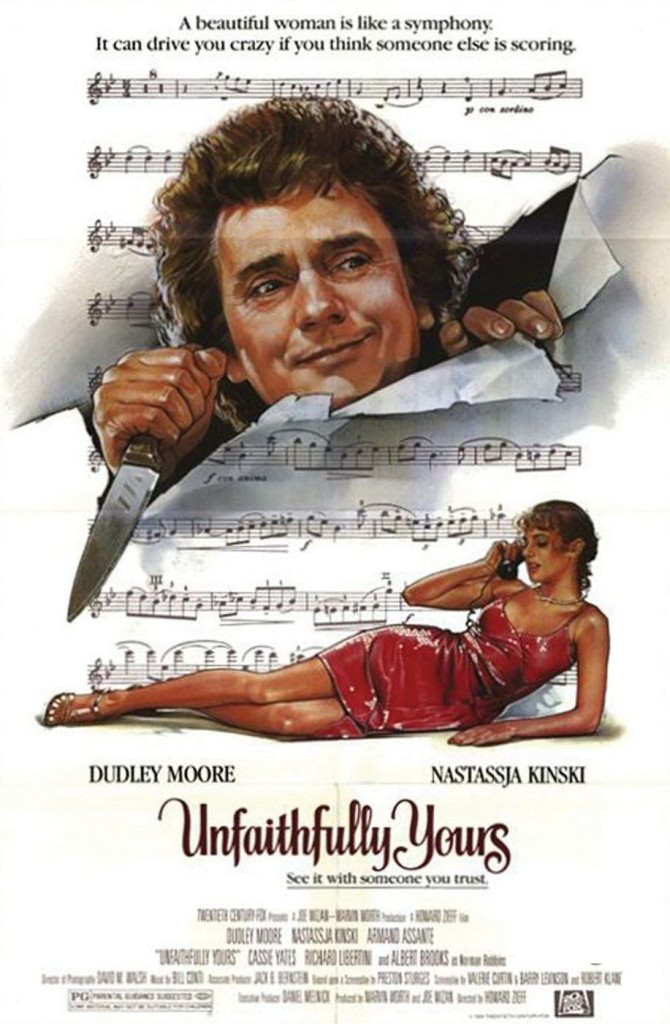

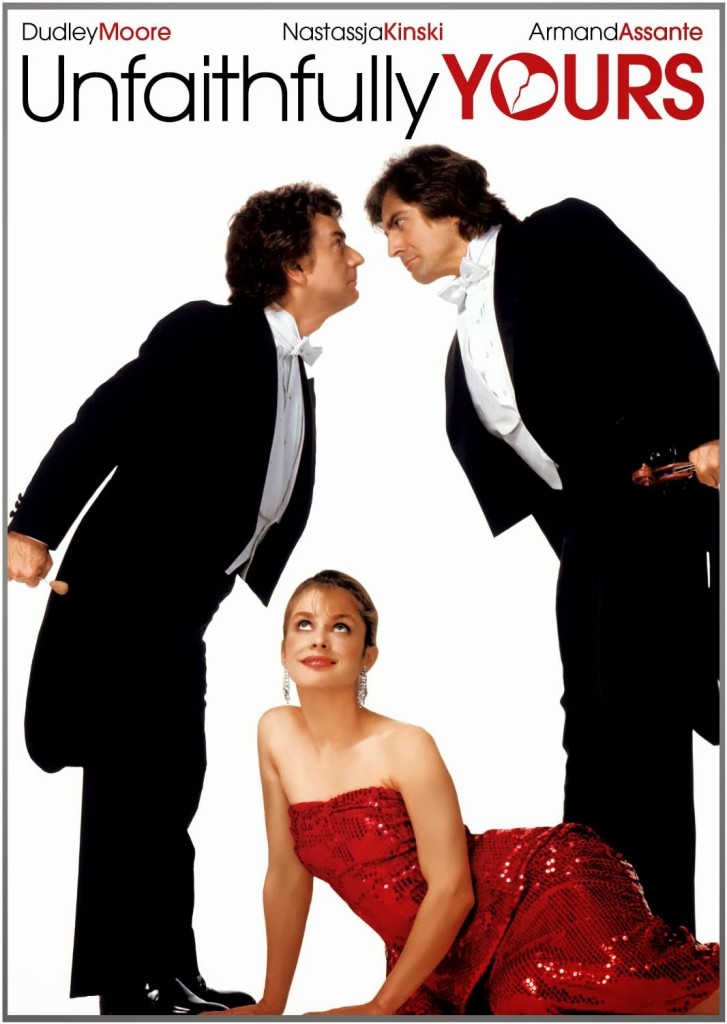

Unfaithfully Yours (1984)

Dir: Howard Zieff

Star: Dudley Moore, Nastassja Kinski, Armand Assante, Albert Brooks

Conductor Claude Eastman (Moore) appears to have everything you could want: a hugely-successful career and a loving, attractive wife, Daniella (Kinski). However, a slight linguistic mix-up around the term “keep an eye on her”, leads to a private investigator being hired to watch Daniella while Claude is out of town. The PI’s report shows an unknown man, wearing Argyle socks, leaving Claude’s apartment in the middle of the night, triggering a tsunami of paranoia in him, that his young wife is cheating on him? When he sees a colleague, concert violinist Max Stern (Assante) wearing socks, and Daniella apparently confesses the affair to him, he concocts a wild plan to murder the pair of lovers and get away with it. However, he is entirely unaware that it’s all a horrible misunderstanding: yes, Max is indeed having an affair, but it’s not with Daniella, and the assignation just happened in their apartment.

Conductor Claude Eastman (Moore) appears to have everything you could want: a hugely-successful career and a loving, attractive wife, Daniella (Kinski). However, a slight linguistic mix-up around the term “keep an eye on her”, leads to a private investigator being hired to watch Daniella while Claude is out of town. The PI’s report shows an unknown man, wearing Argyle socks, leaving Claude’s apartment in the middle of the night, triggering a tsunami of paranoia in him, that his young wife is cheating on him? When he sees a colleague, concert violinist Max Stern (Assante) wearing socks, and Daniella apparently confesses the affair to him, he concocts a wild plan to murder the pair of lovers and get away with it. However, he is entirely unaware that it’s all a horrible misunderstanding: yes, Max is indeed having an affair, but it’s not with Daniella, and the assignation just happened in their apartment.

In some ways, this feels like a compilation put together from elements of Kinski’s previous works. Like Cat People, it’s a remake of a forties movie, in this case, a Preston Sturges pic with Rex Harrison, Linda Darnell and Rudy Vallee as the three leads. Like Spring Symphony, Kinski is again hanging out with a classical musician. And like… oh, just about her entire cinematic output thus far, but particularly Stay as you Are, Kinski is again involved with an older man, Moore being more than 25 years her senior. This leads to allegedly comedic references to Daniella being a “child bride,” which have really not stood the test of time very well. [There was something of the same in the original, but the age difference between Harrison and Darnell was rather less, at about 15 years.]

Obviously, this kind of comedic farce requires a certain amount of disbelief suspension, and needs some careful scripting. The writer needs to take successive elements that seem not to unreasonable in isolation, and use those as building blocks, to create a teetering tower of chaotic misinterpretation and subsequent poor decisions. It’s been some time since I’ve seen the original (also written by Sturges), so I can’t say how much of the apparent problem here were also in the original. But I think the point where I finally toppled over into “I’m so sure…” was with Claude’s plan, where we are expected to believe everyone would mistake the 5’3″ Moore for the 5’10” Assante, even wearing a mask, and especially considering that Kinski splits the difference nicely, at 5’7″.

Another major problem – and I do remember this from the original – is that Dudley Moore is much, much less than Rex Harrison. That’s not really intended as a particular slight on Moore, because just about every actor in the history of cinema is much, much less than Harrison, but it’s certainly an area in which the remake doesn’t match its predecessor. Indeed, that’s probably the main issue here: unlike Cat People, which warped its inspiration into a radically different direction, dragging it kicking and screaming from the era in which it was conceived, Unfaithfully Yours is a much more conventional remake. There’s very little here which doesn’t feels like it could easily have been filmed in the forties, leaving the entire exercise feeling rather pointless, except for cashing out on Moore’s unexpected box-office stardom, in the wake of 10 and Arthur.

Another major problem – and I do remember this from the original – is that Dudley Moore is much, much less than Rex Harrison. That’s not really intended as a particular slight on Moore, because just about every actor in the history of cinema is much, much less than Harrison, but it’s certainly an area in which the remake doesn’t match its predecessor. Indeed, that’s probably the main issue here: unlike Cat People, which warped its inspiration into a radically different direction, dragging it kicking and screaming from the era in which it was conceived, Unfaithfully Yours is a much more conventional remake. There’s very little here which doesn’t feels like it could easily have been filmed in the forties, leaving the entire exercise feeling rather pointless, except for cashing out on Moore’s unexpected box-office stardom, in the wake of 10 and Arthur.

Not that there aren’t some pleasures to be had here. The music is probably among the best of them: Moore was a very talented keyboard player, winning an organ scholarship to Oxford, and a renowned jazz pianist, so we don’t have to endure any of the “actor waves his hands above the keys” fakery. But Assante is pretty convincing too: I don’t know if he has any skills as a violinist, but he certainly gives that impression. Perhaps the film’s most memorable scenes has Claude and Max engaging in “dueling violins” at a restaurant, initially for Daniella’s attention, before it becomes more personal. The whole sequence where Claude’s murder plan plays out in his (literal) mind’s eye, backed by what I think is a Tchakovsky violin concerto, is also well-constructed, and in sharp contrast to the much more messy reality which then transpires.

Not that there aren’t some pleasures to be had here. The music is probably among the best of them: Moore was a very talented keyboard player, winning an organ scholarship to Oxford, and a renowned jazz pianist, so we don’t have to endure any of the “actor waves his hands above the keys” fakery. But Assante is pretty convincing too: I don’t know if he has any skills as a violinist, but he certainly gives that impression. Perhaps the film’s most memorable scenes has Claude and Max engaging in “dueling violins” at a restaurant, initially for Daniella’s attention, before it becomes more personal. The whole sequence where Claude’s murder plan plays out in his (literal) mind’s eye, backed by what I think is a Tchakovsky violin concerto, is also well-constructed, and in sharp contrast to the much more messy reality which then transpires.

Kinski’s role is certainly pivotal, and it’s easily credible how Claude could be concerned about her fidelity, with Assante providing an alternative nearer her own age (at least by the standards of Kinski’s filmography, he being “only” 11 years her senior!). She’s playing an Italian, and does deliver the sparky intensity the stereotypes would demand from that country. Daniella – and, indeed, Max too – actually comes over as much more likeable than Claude, who turns into a shrieking bag of whining insecurities, for which it’s difficult to find much sympathy. His troubles are almost entirely of his own making, and if the ending does fit in with Daniella’s mercurial character, capable of bouncing from love to hate and back again in the blink of an eye, it still seems far too quick, bolted on for the sake of Hollywood convention, instead of flowing organically from what has gone before.

Indeed, there’s also a sharp change in tone between first and second halves, in terms of the style of humor which they use. The latter is much more slapsticky, with Claude staggering around, trying to put his master murder-plan into operation, only for just about everything conceivable to go horribly wrong. There’s something vaguely reminiscent of Fawlty Towers, not just in the Britishness of the leading man, but in the way he plows on towards his goal, even as its obvious he’s doing nothing but digging himself a deeper hole and causing further carnage, when the sensible thing to do would be to cut your losses and give up. Of course, it’s neither as well-written or performed, and unlike Cat People, this remake leaves me with a strong desire to track down and watch the original, and see if it’s really as superior as I remember it.

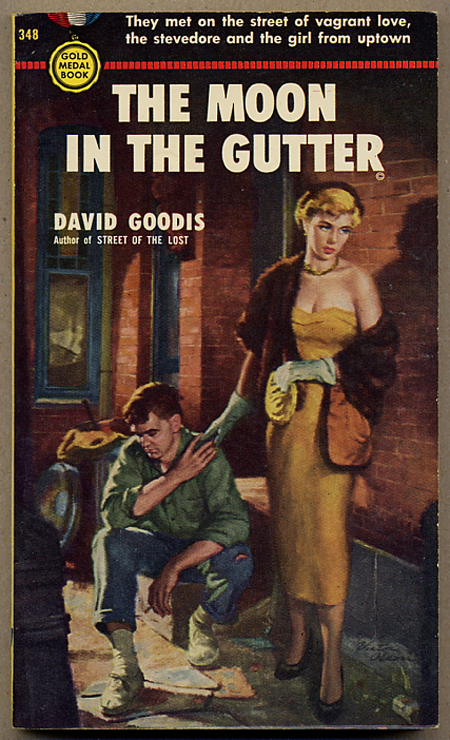

La lune dans le caniveau (1983)

Dir: Jean-Jacques Beineix

Star: Gerard Depardieu, Nastassja Kinski, Victoria Abril, Vittorio Mezzogiorno

We were born in the gutter.

In the water, the stars look at themselves.

— Opening lines

In my mind, Beineix is always linked with Luc Besson, both being French film-makers who burst upon the cinematic scene in the eighties, with the somewhat-similar films Diva and Subway respectively. Besson was the more commercial, and eventually turned into a one-man production factory, writing, producing and occasionally directing slick entertainment. Beineix’s output was more considered, and certainly much less numerous, with only half a dozen narrative features since Diva in 1981. Lune was his second, and demonstrates Beineix’s strong visual sense, though it’s also easy to see why it was a commercial flop. Indeed, when Beineix talked to producing studio Gaumont about releasing a longer cut of the movie, they told him almost all additional footage had been destroyed, seen as having no possible future value.

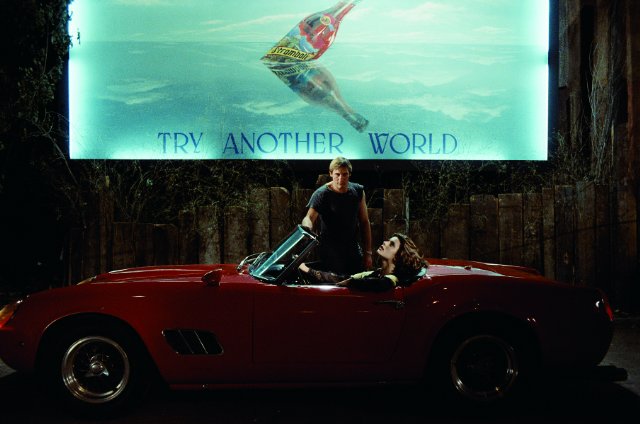

It’s set in the hellish environment down by the Marseilles docks, where Gerard (Depardieu) works, spending his nights gazing at the spot where his sister committed suicide, following her rape by an unknown assailant. Gerard dreams of finding the person responsible and extracting revenge, until the Channing siblings enter his world from their privileged existence uptown. Newton (Mezzogiorno) slums it, trying to forget his involvement in the car-crash which killed their parents by engaging in bizarre bar-bets with the locals – Gerard wins by eating through a block of ice. Loretta (Kinski) picks her brother up in her vintage Ferrari 250 GT California Spyder – one of the few times Kinski is comprehensively out-classed in the beauty department – but meets Gerard in the same bar, and there’s an instant magnetism. There begins a tempestuous relationship – one which leaves Gerard’s current girlfriend, Bella (Abril), more than somewhat disgruntled.

It’s set in the hellish environment down by the Marseilles docks, where Gerard (Depardieu) works, spending his nights gazing at the spot where his sister committed suicide, following her rape by an unknown assailant. Gerard dreams of finding the person responsible and extracting revenge, until the Channing siblings enter his world from their privileged existence uptown. Newton (Mezzogiorno) slums it, trying to forget his involvement in the car-crash which killed their parents by engaging in bizarre bar-bets with the locals – Gerard wins by eating through a block of ice. Loretta (Kinski) picks her brother up in her vintage Ferrari 250 GT California Spyder – one of the few times Kinski is comprehensively out-classed in the beauty department – but meets Gerard in the same bar, and there’s an instant magnetism. There begins a tempestuous relationship – one which leaves Gerard’s current girlfriend, Bella (Abril), more than somewhat disgruntled.

Beineix’s subsequent Betty Blue was a rather more successful picture of a damaged couple: here, it’s never particularly convincing, with Gerard and Loretta apparently intent on making each other as unhappy as possible. That may be the point, as no-one here seems exactly content: Bella’s insanely jealous of even the most innocent of interactions, to the extent that you can hardly blame Gerard for cheating on her, since he’s going to be accused of doing that anyway. He doesn’t exactly have the greatest of relationship examples around him, with his father stuck in a hellish one with a large, black woman, who berates him from pillar to post. On that basis, you can understand Gerard leaping at anything which offers a lifeline – it’s clear that the “moon” of the title is Loretta, but she is ultimately as unreachable as that satellite, from the gutter in which he lives. This is doomed from the get-go.

Beineix’s subsequent Betty Blue was a rather more successful picture of a damaged couple: here, it’s never particularly convincing, with Gerard and Loretta apparently intent on making each other as unhappy as possible. That may be the point, as no-one here seems exactly content: Bella’s insanely jealous of even the most innocent of interactions, to the extent that you can hardly blame Gerard for cheating on her, since he’s going to be accused of doing that anyway. He doesn’t exactly have the greatest of relationship examples around him, with his father stuck in a hellish one with a large, black woman, who berates him from pillar to post. On that basis, you can understand Gerard leaping at anything which offers a lifeline – it’s clear that the “moon” of the title is Loretta, but she is ultimately as unreachable as that satellite, from the gutter in which he lives. This is doomed from the get-go.

While the film never treats any of its characters particularly well, the film is shot through with an almost casual misogyny. Gerard smacks both Bella and Loretta around at various points: rather than telling him to go fuck himself, they both apparently accept it as the price of his company, and a cost they’re willing to pay. Just about every woman depicted in the film is a whore, a shrew, mentally unstable, or some combination of the above. Gerard’s sister is about the sole exception, and she’s dead; I’m not certain which categories cover Loretta. Not that the men come off as paragons of virtue. There isn’t much reason why anyone would want to spend time with them either, and that’s what makes this different from something like A Streercar Named Desire, where Marlon Brando imbued its flawed lead with a noble savagery of emotion.

What does work, and works to excellent effect, is the visual style. While largely disparaged at the time (and rightly so, for it’s certainly overlong, and often painfully dull), it fully deserves the César award it received for Best Production Design, because the hovels and slums are made to look absolutely stunning. There are a few sequences which have a utter dreamlike quality to them, to a degree that there were times when I was left wondering if the entire thing is intended to be a product of Gerard’s deranged imagination, such as when he and Loretta are driving around the docks in her Ferrari. But it’s cinema as Turner sea-scape: something you might want to hang on your wall, yet not something capable of sustaining your interested for comfortably more than two hours. By the end, it’s hard to see how anyone has truly been changed by their experiences, and there’s a sense you’re right back where you started.

I was surprised to discover that this was not an original story, but based on a book written back in 1953 by American pulp noir author, David Goodis. His version was, unsurprisingly, not located in Marseilles but Philadelphia: the central character’s name was Bill Kerrigan rather than Gerard Delmas, but Beineix retained the name of the heroine, despite it being distinctly non-Gallic. One Amazon review says, “Kerrigan’s world consists of overcrowded tenements, rundown shacks and two-bit bars populated by has beens, never will bes, winos, hookers and derelicts of every description. This is a world completely bereft of hope, a world from which there can be no escape.” Beineix certainly nails that: between this and the similarly-grim Last Exit to Brooklyn, written by Hubert Selby and directed by Uli Edel, it seems downbeat tales of low-life love and loss have a certain resonance with European film-makers.

I was surprised to discover that this was not an original story, but based on a book written back in 1953 by American pulp noir author, David Goodis. His version was, unsurprisingly, not located in Marseilles but Philadelphia: the central character’s name was Bill Kerrigan rather than Gerard Delmas, but Beineix retained the name of the heroine, despite it being distinctly non-Gallic. One Amazon review says, “Kerrigan’s world consists of overcrowded tenements, rundown shacks and two-bit bars populated by has beens, never will bes, winos, hookers and derelicts of every description. This is a world completely bereft of hope, a world from which there can be no escape.” Beineix certainly nails that: between this and the similarly-grim Last Exit to Brooklyn, written by Hubert Selby and directed by Uli Edel, it seems downbeat tales of low-life love and loss have a certain resonance with European film-makers.

“Try another world” says the billboard (above), situated opposite Gerard’s home, in a particularly unsubtle bit of self-fulfilling commentary – in Beineix’s defense, it is in English, which likely makes it stand out more to non-French viewers. I guess the moral here is, just as advertising is not always truthful, the world you strive to reach might prove to be as ultimately unsatisfying as this one. That hardly feels much of a worthwhile revelation, personally, and perhaps I dare only whisper it, but Gaumont’s loss of the additional footage is probably no bad thing. The prospect of sitting through a reported four-hour version of this, would likely have me gnawing off a limb to escape.