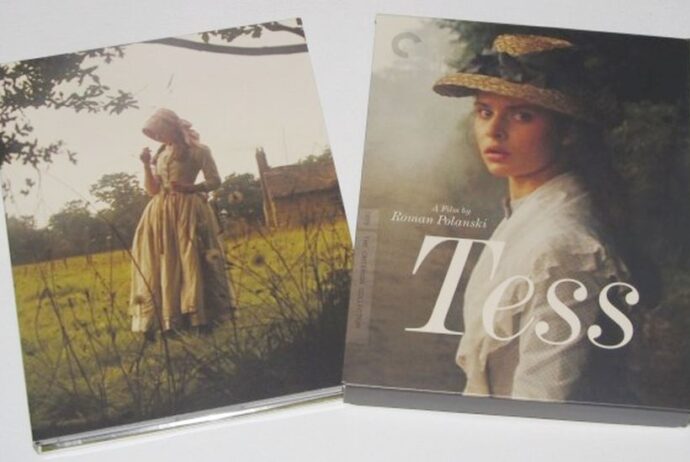

Over Thanksgiving, I finally had a chance to settle down with the Criterion Collection edition of Tess. There was a while where I didn’t buy any physical media at all, but it’s something I’ve been getting back into, being aware that streaming is not a reliable or permanent way to have access to favored movies. One such purchase was the Criterion Blu-Ray of Tess, which in addition to the film, contains almost four hours of extras. Here, I don’t really want to discuss the movie. I’ve already talked about it, though the Criterion copy is gorgeous: it is truly one of the most beautiful movies ever made. Instead, I want to talk about the extras, and what they bring to my appreciation of the film.

Ciné Regards (49 minutes)

This is a 1979 episode of French television program Ciné regards. It mixes behind-the-scenes footage from the making of the film in the French countryside, and an interview with director Roman Polanski. I hadn’t realized how long the production was here. There’s footage of shooting at ‘Stonehenge’, labelled “Day 154“! It’s an impressively multi-lingual production, Polanski switching between discussions in English (for the cast) and French, when speaking to the crew. He’s also remarkably patient. After one take, apparently derailed by noise from spectators, he saunters over and – far more agreeably than I would – explains that the shot takes half an hour to set-up, and politely asks them to be quiet, otherwise, they will have to move back.

The most interesting section comes when they’re shooting the scene where Tess boards the train after killing Alec, and reunited with Angel. I didn’t realize this was done with rear projection, and from outside the carriage, you see Nastassja fake-“walking”, and also having major problems with the carriage door! There are also some great quotes from Polanski in regard to his lead actress:

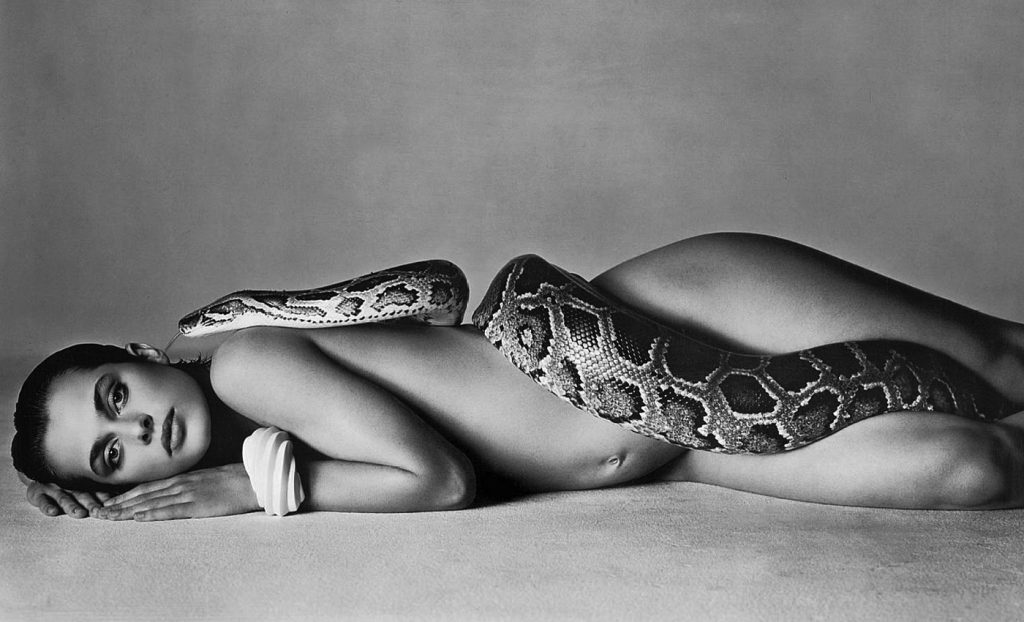

She has this aura, this atmosphere she creates, that’s just like what I most love about old movies. She reminds me of a young Audrey Hepburn or Vivien Leigh. When men see her onscreen, they want to protect her. It’s an essential quality for a woman on the screen… She has one of those vulnerable faces that can move us even when still. She has a face that can handle every angle, every light, without worrying about her “best side”.

On the other hand, he says had he realized the work involved in the role, he might not have cast someone so inexperienced. Still, worked out in the end! I didn’t know Polanski started out as an actor. Frankly, having seen the comic mugging which passes for a performance in The Fearless Vampire Killers, I think he was considerably better behind the camera!

Once Upon a Time… Tess (53 minutes)

This extra looks to be an episode from a 2006 French series called A Film and Its Era. As the clip above shows, it’s particularly interested in putting the film in the context of the its era. Directed by Daniel Ablin and Serge July, it contains interviews with Polanski, Kinski, actor Leigh Lawson, plus producer Claude Berri, costume designer Anthony Powell, and composer Philippe Sarde. It talks about how it was the most expensive film ever made in France to that point, with Berri having to put all his own money into the production, which had to have been utterly nerve-wracking (fortunately, it turned out well enough from a financial perspective).

One interesting point is Nastassja saying she could relate to Tess and her trauma. “Because she was so young… and many serious and painful things happened to her.” That quote immediately caused me to think about the subsequent claims of abuse made about their father, Klaus, by her sister, Pola, Later, she says Polanski was “Often a father figure to me… That comes from not really having a family background.” Read into that what you like. She also discussed her brief time in juvenile detention. Powell is a very good interview, and discussed in detail his choices with regard to Tess’s wardrobe. In particular, how he avoided color until after her murder of Alec, when the character then dons a dress the shade of dried blood. He says of Nastassja, “I think that her great gift was an instinctual intelligence – intelligence that came not from the head but the heart… She is a perfect director’s tool.”

Polanski talks about his early life, and his experience of soup. He was actually born in Paris before his family returned to Poland, but his mother died in Auschwitz concentration camp during World War II. This section is almost the only one to mention the awkward elephant in the room, and the reason why the film could not be made in England where it’s set. Though the doc seems rather friendly, calling what happened a “consenting sexual relationship with a 14-year-old.” That kind of thing might fly in France, but America and the UK feel differently. Another interesting nugget though: Polanski was so depressed by the post-production experience (more on which later), he went off to do theater, and wouldn’t direct another film for almost seven years.

From Novel to Screen (29 minutes)

This, as well, as the next two extras, were all directed by Laurent Bouzereau in 2004, to accompany the regular DVD release of the movie. They’ve been ported over from that edition to the Blue-Ray. This one covers the pre-production process, and it appears the original version of the script, by Polanski and Gerard Brach, was in French. Producer Berri remembers Roman showed up on the doorstep of producer Claude Berri around midnight, with Nastassja in tow. “I was mesmerized by her beauty… I immediately thought, this is going be fantastic.” However, the British actor’s union Equity were very unhappy about a German girl playing the lead in a British movie. However, the casting people simply couldn’t find anyone better.

The question of whether she could master the Dorset accent was a significant one. Before Nastassja signed, she worked with dialogue coach Kate Fleming and then shot some test footage. Polanski said, “We were all astonished by the progress and how well she spoke with the accent.” This section also has a great discussion on the costumes and locations used in the film. As well as the, um, legal reasons, it appears the French landscape was a better reflection of what farms looked like in Hardy’s time. In England, the process of agricultural modernization had taken significant hold, with fields no longer looking like they had in the nineteenth century.

Filming Tess (26 minutes)

A documentary dealing with the production, and Berri says “It was clear that Roman was the orchestra leader.” He remembers once visiting the set and giving some advice to Leigh Lawson. Roman just glared at him. Part of the reason why the shoot took so long was because Polanski took however long was necessary to achieve perfection. Powell remembers a time where Kinski was kept standing in one place for so long, that a spider actually began weaving a web between her and the camera. It became something of a standing joke between them, over the rest of the film’s extended production. Co-producer Timothy Burrill remembers, “The extraordinary professionalism of Nastassja, who worked like nobody worked. I don’t think there was one day where she fluffed a line, she was word-perfect always.”

On the first day, the greenhouse location looked far more run-down than it should, so everyone had to pile in and help paint it. It was also the day when they shot arguably the most famous scene in the film, when Tess eats a strawberry out of the fingers of Alec. This section also discusses the death during filming of Geoffrey Unsworth, who passed away from a heart attack about three months into shooting. Nastassja gets visibly choked up discussing this, and it’s amazing how replacement Ghislain Cloquet was able to take over and reproduce Unsworth’s style. The two men shared the 1980 Academy Award for Best Cinematography, and it’s one which I would say was fully deserved.

Tess: The Experience (20 minutes)

I’m not quite sure what the general topic is here. It’s a little about production, a little about the post-production process. Leigh Lawson praised the unified cast/crew dynamic, which saw them often hanging out together after filming was over for the day, sometimes taking over whatever local facility was available. Nastassja turned eighteen during the production (presumably in January 1979). She was thrown a surprise party for her birthday, and was given a car by Roman as a present. There were problems at the end, because the set intended for use during the movie’s finale at Stonehenge, was locked up due to a strike, and they were lucky it was released in time for shooting to proceed.

As mentioned before, the post-production process was fraught, editing the film down from its initial cut of 187 minutes, and dealing with Dolby sound issues. At one point, Polanski and his editors worked on the film for twenty-six and a half hours without stopping. The director came under pressure, including from Francis Ford Coppola, to edit the film down, but largely held his ground, with the director-approved version coming in with a running time of 170 minutes. Though according to Polanski here, he hasn’t seen the film for years: I wonder if that still remains the case today? He was in attendance for the premiere of the restored version in 2012 at Cannes, but did he actually watch it?

The South Bank Show: Roman Polanski (50 minutes)

It was one of the longest-running arts shows in British TV history, with over eight hundred episodes between 1978 and 2023, all hosted by Melvin Bragg. This edition, originally aired on May 25, 1980, features an interview with Polanski. While certainly interesting, since it covers his entire career, is probably the least of direct relevance to us here. He does mention Nastassja, saying of her, “At least physically, she was exactly the description of Hardy’s… But there’s something more about her, she’s got this vulnerability that certain women of the screen have.” These comments echo the ones made previously in the extras, as quoted above.

In the introduction, Bragg does mention Polanski’s status as a fugitive, but makes it clear this interview would not be covering the topic. It does leave me curious to see some early Polanski, like Knife in the Water. I also realized my first exposure to the director was back in school, where they showed us his version of Macbeth. This play was covered every damn year in English class, because it took place in the area of Scotland where I grew up – my home town is even name-checked in the first scene. But I suspect whoever organized the screening didn’t quite realize the amount of sex and nudity present in this version! The fact it was partly funded by Hugh Hefner of Playboy fame, might have been a clue!

Conclusion

No doubt, I’d have been entirely happy had the Blu-Ray simply included a good quality transfer of the film, without any extras. That’s what truly matters, and I’m more likely to revisit the movie again, than any of the supplementary features. That said, I did gain an additional appreciation for the film from the wealth of information regarding its production, and the next time I watch it, this will inform my enjoyment. I was left wondering if this kind of movie is a product of a bygone era, when committed artists were allowed to spend ten months assembling, what’s basically a three-hour art-house flick.

If you would like to just check out the additional features, all of them, except for The South Bank Show, are available (at least, here in the US), on the Criterion Channel, along with the movie itself. You can even get a seven-day free trial of the service if you want to do so. But I’d have no qualms about recommending you get the Blu-Ray, It’s a top-tier presentation of what’s arguably Nastassja’s highest quality movie.