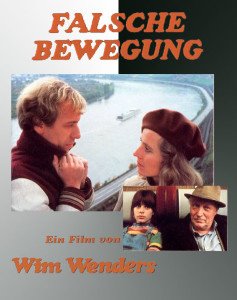

Dir: Wim Wenders

Star: Rüdiger Vogler, Hanna Schygulla, Hans Christian Blech, Nastassja Kinski (as Nastassja Nakszynski).

The opening scene has the hero, Wilhelm (Vogler) observing people in the city square below his bedroom window. Suddenly, without explanation, he puts his fist through the glass. His mother comes to see what has happened – she opens the bedroom door, stares at Wilhelm, who stares back, without either of them saying a single word – such as (and I’m just improvising here), “What the heck happened to the window, and why is your hand bleeding?” Instead, after exchanging gazes, she closes the door, and your humble reviewer literally bursts out laughing, at the pretentious angst-laden weight of it all.

This is the kind of seventies artwank for which I have little time and even less love, with Wilhelm being emo in all the worst ways, about a decade before the term was even invented. That means: self-obsessed, introverted and in love with the sound of his own inner monologue, even though he doesn’t have much of interest to say. But then, the same could be said for just about everyone else in the movie. Even the conductor on the train, as Wilhelm heads to Bonn to seek his fortune as a writer, doesn’t just sell tickets, he also expresses his angst: “Something terrible happened to me today. I leave the house, and when I’m outside I notice I’ve forgotten my umbrella. I opened it up. I had odd-colored socks on too. It was indescribable.”

Ah, the ennui is overpowering, to quote Marvin the Paranoid Android (not the last Hitch-hiker’s Guide reference in this paragraph, either). On his journey, Wilhelm turns out to be a bit of a Pied Piper of Angst, attracting a palette of other characters around him, who act in a similar fashion, as if their banal pronouncements shed some light on the meaning of life. For instance, there’s actress Therese (Schygulla), street performer, and likely unreconstructed Nazi, Laertes (Blech) his pubescent assistant Mignon (Kinski), and wannabe poet Bernard, whose output is so execrably bad, it’d give Vogon poetry a run for its money. Let’s just enjoy a sample, shall we?

A child trod on me, like on snail-festooned jellied, rotting fungus.

I yearned to spurt myself into the gutter.

I felt like trembling, transparent veal jelly.

I fell though a trap-door into a last dream and hung like well-hung meat on a hook.

And a hanged man with a sign: “I AM A TRAITOR” twitched as MYSELF from a plum tree.

From my terror-stricken stiff member there shot sperm and dripped upon a white sheet.

Since then I’ve lived under a glass bell and let my rotting consciousness vapour the glass.

Why must there be so vast a space between me and the world?

Bernard fits right in, needless to say. Reaching Bonn, they wander through the backstreets of the capital, observing the sickness of the human condition: a couple fighting here, a man howling from a window there. The only time any enthusiasm is detected in the group, is when they see what appears to be a fire and rush off to see it. Maybe someone is burning to death in there. They end up at a castle supposedly belonging to Bernard’s uncle, but it’s the wrong house, and they interrupt the owner, just as he is about to commit suicide, following his wife, who did so three months previously. After listening to his monologue, beginning, “I’d like to talk about loneliness. I don’t believe it exists. It’s more of an artificial feeling engendered from outside,” I can see why she opted for suicide. And after one night with the group, the house-holder too, opts to return to his original plan, and kills himself.

Bernard fits right in, needless to say. Reaching Bonn, they wander through the backstreets of the capital, observing the sickness of the human condition: a couple fighting here, a man howling from a window there. The only time any enthusiasm is detected in the group, is when they see what appears to be a fire and rush off to see it. Maybe someone is burning to death in there. They end up at a castle supposedly belonging to Bernard’s uncle, but it’s the wrong house, and they interrupt the owner, just as he is about to commit suicide, following his wife, who did so three months previously. After listening to his monologue, beginning, “I’d like to talk about loneliness. I don’t believe it exists. It’s more of an artificial feeling engendered from outside,” I can see why she opted for suicide. And after one night with the group, the house-holder too, opts to return to his original plan, and kills himself.

That night Wilhelm ends up – accidentally or not – in Mignon’s room, where she is sprawled, topless, awaiting his attention. This is “a bit troubling,” shall we say, since Kinski was probably only 13 at the time of filming, given the film’s premiere was March 1975, seven weeks after her birthday. So don’t expect a screenshot of it here. Fortunately for the film’s legal status, he slaps her and leaves. The next day the group exchange dreams and go for a walk, on which Bernard and Wilhelm have a conversation. It’s notable, because it’s one of the few times characters talk to each other, rather than pontificating at each other, without the slightest apparent interest in listening to anyone else.

It’s probably this which makes the film so irritating. Peter Handke’s screenplay (inspired by Goethe’s novel, Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship) seems more interested in using the characters as a mouthpiece for his own views, than bringing them to life of their own. The group slowly disintegrates., Wilhelm observing the banality of the everyday life which surrounds him, and never getting round to doing much in the way of writing. His cold disinterest eventually drives even Therese away, reducing her to empty gestures, flailing ineffectually at Wilhelm with paper snatched from his typewriter.

Really, Kinski’s character comes over as perhaps the most sympathetic in the entire film – because she is completely mute, and so doesn’t have to spout the turgid, pseudo-philosophical nonsense which comes out of the mouths of everyone else. It’s probably wise, given her complete lack of acting ability or training, and instead, she just observes what’s going on – her silence (never explained or even addressed) makes her seem a lot smarter than most of the adults. The luminous gaze that would bring her to international stardom down the line, is already completely recognizable, and its understandable why Wenders discovered her in a Munich disco, apparently oblivious to her parentage.

I get the fact that this is all intended to be an allegory for the state of Germany in the mid-70’s, with Mignon representing the nation’s youth, and Laertes its dubious recent past, for instance. But any relevance is severely diluted by the passage of close to forty years, as well as several thousand miles of geographical distance. Now, what you have is instead a parade of unlikeable, selfish characters wandering around an emotional wasteland, while preening in their intellectual mirrors. It ends – and I trust I’m not spoiling this for anyone – with Wilhelm as alone as he was when the movie started, apparently unchanged and unmoved by his experiences. As character arcs go, it’s nothing to write home about.