Dir: Jean-Jacques Beineix

Star: Gerard Depardieu, Nastassja Kinski, Victoria Abril, Vittorio Mezzogiorno

We were born in the gutter.

In the water, the stars look at themselves.

— Opening lines

In my mind, Beineix is always linked with Luc Besson, both being French film-makers who burst upon the cinematic scene in the eighties, with the somewhat-similar films Diva and Subway respectively. Besson was the more commercial, and eventually turned into a one-man production factory, writing, producing and occasionally directing slick entertainment. Beineix’s output was more considered, and certainly much less numerous, with only half a dozen narrative features since Diva in 1981. Lune was his second, and demonstrates Beineix’s strong visual sense, though it’s also easy to see why it was a commercial flop. Indeed, when Beineix talked to producing studio Gaumont about releasing a longer cut of the movie, they told him almost all additional footage had been destroyed, seen as having no possible future value.

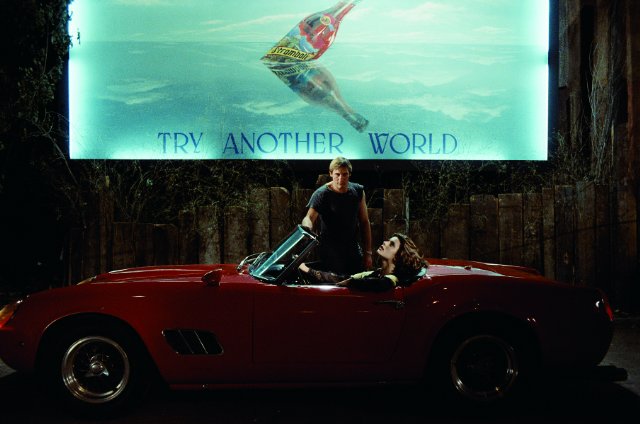

It’s set in the hellish environment down by the Marseilles docks, where Gerard (Depardieu) works, spending his nights gazing at the spot where his sister committed suicide, following her rape by an unknown assailant. Gerard dreams of finding the person responsible and extracting revenge, until the Channing siblings enter his world from their privileged existence uptown. Newton (Mezzogiorno) slums it, trying to forget his involvement in the car-crash which killed their parents by engaging in bizarre bar-bets with the locals – Gerard wins by eating through a block of ice. Loretta (Kinski) picks her brother up in her vintage Ferrari 250 GT California Spyder – one of the few times Kinski is comprehensively out-classed in the beauty department – but meets Gerard in the same bar, and there’s an instant magnetism. There begins a tempestuous relationship – one which leaves Gerard’s current girlfriend, Bella (Abril), more than somewhat disgruntled.

It’s set in the hellish environment down by the Marseilles docks, where Gerard (Depardieu) works, spending his nights gazing at the spot where his sister committed suicide, following her rape by an unknown assailant. Gerard dreams of finding the person responsible and extracting revenge, until the Channing siblings enter his world from their privileged existence uptown. Newton (Mezzogiorno) slums it, trying to forget his involvement in the car-crash which killed their parents by engaging in bizarre bar-bets with the locals – Gerard wins by eating through a block of ice. Loretta (Kinski) picks her brother up in her vintage Ferrari 250 GT California Spyder – one of the few times Kinski is comprehensively out-classed in the beauty department – but meets Gerard in the same bar, and there’s an instant magnetism. There begins a tempestuous relationship – one which leaves Gerard’s current girlfriend, Bella (Abril), more than somewhat disgruntled.

Beineix’s subsequent Betty Blue was a rather more successful picture of a damaged couple: here, it’s never particularly convincing, with Gerard and Loretta apparently intent on making each other as unhappy as possible. That may be the point, as no-one here seems exactly content: Bella’s insanely jealous of even the most innocent of interactions, to the extent that you can hardly blame Gerard for cheating on her, since he’s going to be accused of doing that anyway. He doesn’t exactly have the greatest of relationship examples around him, with his father stuck in a hellish one with a large, black woman, who berates him from pillar to post. On that basis, you can understand Gerard leaping at anything which offers a lifeline – it’s clear that the “moon” of the title is Loretta, but she is ultimately as unreachable as that satellite, from the gutter in which he lives. This is doomed from the get-go.

Beineix’s subsequent Betty Blue was a rather more successful picture of a damaged couple: here, it’s never particularly convincing, with Gerard and Loretta apparently intent on making each other as unhappy as possible. That may be the point, as no-one here seems exactly content: Bella’s insanely jealous of even the most innocent of interactions, to the extent that you can hardly blame Gerard for cheating on her, since he’s going to be accused of doing that anyway. He doesn’t exactly have the greatest of relationship examples around him, with his father stuck in a hellish one with a large, black woman, who berates him from pillar to post. On that basis, you can understand Gerard leaping at anything which offers a lifeline – it’s clear that the “moon” of the title is Loretta, but she is ultimately as unreachable as that satellite, from the gutter in which he lives. This is doomed from the get-go.

While the film never treats any of its characters particularly well, the film is shot through with an almost casual misogyny. Gerard smacks both Bella and Loretta around at various points: rather than telling him to go fuck himself, they both apparently accept it as the price of his company, and a cost they’re willing to pay. Just about every woman depicted in the film is a whore, a shrew, mentally unstable, or some combination of the above. Gerard’s sister is about the sole exception, and she’s dead; I’m not certain which categories cover Loretta. Not that the men come off as paragons of virtue. There isn’t much reason why anyone would want to spend time with them either, and that’s what makes this different from something like A Streercar Named Desire, where Marlon Brando imbued its flawed lead with a noble savagery of emotion.

What does work, and works to excellent effect, is the visual style. While largely disparaged at the time (and rightly so, for it’s certainly overlong, and often painfully dull), it fully deserves the César award it received for Best Production Design, because the hovels and slums are made to look absolutely stunning. There are a few sequences which have a utter dreamlike quality to them, to a degree that there were times when I was left wondering if the entire thing is intended to be a product of Gerard’s deranged imagination, such as when he and Loretta are driving around the docks in her Ferrari. But it’s cinema as Turner sea-scape: something you might want to hang on your wall, yet not something capable of sustaining your interested for comfortably more than two hours. By the end, it’s hard to see how anyone has truly been changed by their experiences, and there’s a sense you’re right back where you started.

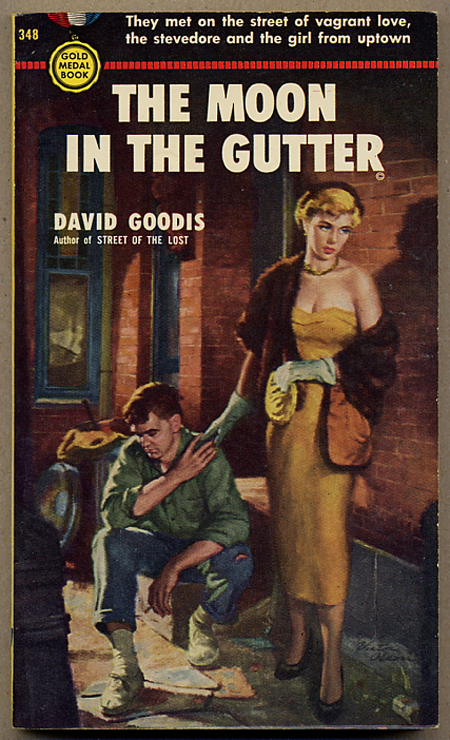

I was surprised to discover that this was not an original story, but based on a book written back in 1953 by American pulp noir author, David Goodis. His version was, unsurprisingly, not located in Marseilles but Philadelphia: the central character’s name was Bill Kerrigan rather than Gerard Delmas, but Beineix retained the name of the heroine, despite it being distinctly non-Gallic. One Amazon review says, “Kerrigan’s world consists of overcrowded tenements, rundown shacks and two-bit bars populated by has beens, never will bes, winos, hookers and derelicts of every description. This is a world completely bereft of hope, a world from which there can be no escape.” Beineix certainly nails that: between this and the similarly-grim Last Exit to Brooklyn, written by Hubert Selby and directed by Uli Edel, it seems downbeat tales of low-life love and loss have a certain resonance with European film-makers.

I was surprised to discover that this was not an original story, but based on a book written back in 1953 by American pulp noir author, David Goodis. His version was, unsurprisingly, not located in Marseilles but Philadelphia: the central character’s name was Bill Kerrigan rather than Gerard Delmas, but Beineix retained the name of the heroine, despite it being distinctly non-Gallic. One Amazon review says, “Kerrigan’s world consists of overcrowded tenements, rundown shacks and two-bit bars populated by has beens, never will bes, winos, hookers and derelicts of every description. This is a world completely bereft of hope, a world from which there can be no escape.” Beineix certainly nails that: between this and the similarly-grim Last Exit to Brooklyn, written by Hubert Selby and directed by Uli Edel, it seems downbeat tales of low-life love and loss have a certain resonance with European film-makers.

“Try another world” says the billboard (above), situated opposite Gerard’s home, in a particularly unsubtle bit of self-fulfilling commentary – in Beineix’s defense, it is in English, which likely makes it stand out more to non-French viewers. I guess the moral here is, just as advertising is not always truthful, the world you strive to reach might prove to be as ultimately unsatisfying as this one. That hardly feels much of a worthwhile revelation, personally, and perhaps I dare only whisper it, but Gaumont’s loss of the additional footage is probably no bad thing. The prospect of sitting through a reported four-hour version of this, would likely have me gnawing off a limb to escape.