Dir: Andre Farwagi

Star: Nastassja Kinski, Gerry Sundquist, Marion Kracht, Véronique Delbourg

“St Clare’s School a brothel? This is the greatest offer I’ve ever heard, boys.”

In its dubbed incarnation as Passion Flower Hotel, this was the first Kinski film I saw, when it was screened overnight on ITV, I’m guessing probably in the late eighties, and at the time, I thought it (and Kinski in particular) was the greatest thing since sliced bread. It was the beginning of a lengthy fascination with Nastassja, that lasted a decade, was derailed when a psychotically jealous girlfriend decided to cleanse my life of her (I should have taken the hint when video sleeves started turning up with their eyes gouged out!) , and declined into irrelevance, as I became the happily-married man I am now. But my fondness for trash cinema and writing about it remains intact (on Monday, I did 500 words on Sharknado, which irreparably timestamps this post at July 2013!), and this film was one of the formative influences.

Of course, things have changed since: mostly me. It’s one thing to watch a film which depicts teenage girls as sex objects when you’re the same age yourself. At that point, it was hard to conceive of a finer prospect than the 17-year-old Kinski. Now, I’m married, with a daughter who is older than that, and it just seems…wrong, and I feel wrong for watching it. [Though as we’ll see, its creator seemed to feel no such qualms] Of course, it’s the cheerily transgressive nature of the movie which was part of its original appeal. Even in the decade between its release and my discovery, AIDS had turned sex into a death sentence, and the concept of a lighthearted romp involving underage girls selling their virginities, was already insanely inappropriate, albeit in ways not perhaps foreseeable when the book that inspired it came out, in 1962.

“It would have been shocking anywhere, but that it should happen at Bryant House, an expensive and exclusive girls’ boarding school, was incredible – at least, to the authorities. Sarah Callender was receiving excellent instruction in cookery, home-nursing, needlework, languages and games, but she was deeply disturbed by an obvious omission from the curriculum. So during her Christmas holidays she did some unusual research and discovered that boys in boarding schools were being neglected in the same subject. There was no alternative: they must educate themselves.”

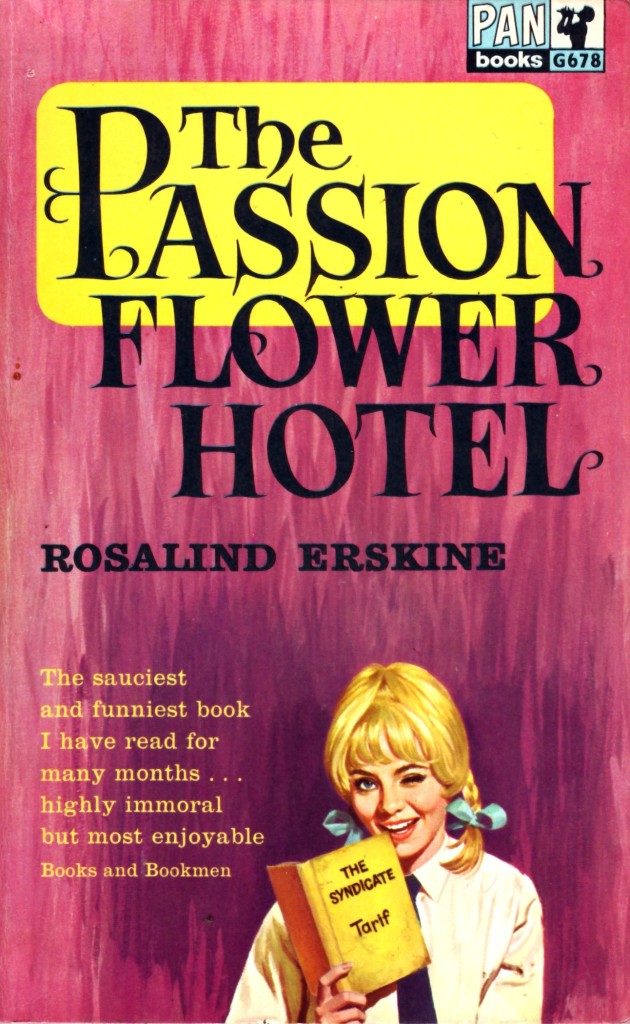

The book, The Passion Flower Hotel, was written by “Rosalind Erskine”. Quotes used advisedly: rather than the supposed teenage girl author this was one of many pseudonyms adopted by Roger Longrigg. A prolific author, then in his mid-thirties. he also wrote, under another pen-name, Mother Love, adapted into a successful BBC TV series starring Diana Rigg. Predating the movie, the book became a musical play, with a score by John Barry, composer of the Bond theme. That ran in Manchester and London’s West End over the summer of 1965, with the cast including Barry’s future wife Jane Birkin and Pauline Collins, later to become Shirley Valentine, and also Francesca Annis. [Warner Bros apparently had optioned the play’s movie rights, but nothing came of it]. In the mid-eighties, however, the novel also became a BBC radio dramatization, for which I’ve just located a source, and it’s something I am quite curious to hear.

The book, The Passion Flower Hotel, was written by “Rosalind Erskine”. Quotes used advisedly: rather than the supposed teenage girl author this was one of many pseudonyms adopted by Roger Longrigg. A prolific author, then in his mid-thirties. he also wrote, under another pen-name, Mother Love, adapted into a successful BBC TV series starring Diana Rigg. Predating the movie, the book became a musical play, with a score by John Barry, composer of the Bond theme. That ran in Manchester and London’s West End over the summer of 1965, with the cast including Barry’s future wife Jane Birkin and Pauline Collins, later to become Shirley Valentine, and also Francesca Annis. [Warner Bros apparently had optioned the play’s movie rights, but nothing came of it]. In the mid-eighties, however, the novel also became a BBC radio dramatization, for which I’ve just located a source, and it’s something I am quite curious to hear.

There were actually three books, the sequels being Passion Flowers in Italy and Passion Flowers in Business, but it’s only the first which has any culture resonance, and still seems to be remembered quite fondly – its Goodreads.com rating is a healthy 3.9 out of five stars. There’s a Books Monthly feature article that is quite effusive in its praise, calling central character Sarah Callender, “the culmination of all those fantastic school story heroines.” But it makes the credible point that the book came out just after Lady Chatterley’s Lover, which marked a ‘great leap forward’ in permissiveness for literature, one authors were keen to exploit. However, it also remains resolutely homophobic, as witnessed by the following exchange between Sarah and one of her prospective clients at the neighbouring school:

‘Don’t you have romantic feelings for smaller boys?’

‘When did you ever hear that?’

‘I suppose I read it.’

‘Only perverted swine go in for that sort of thing.’

Ironic how society’s attitudes have gone the opposite way in this, compared to the core concept here. There’s one odd scene – odd, mostly because it’s a musical number! – where the boys get lessons in kissing, which ends with some brief male on male action. But it’s not an idea more than vaguely broached by the film version on which we’re focused, despite the obvious possibilities inherent in schoolgirl lesbian lust. Yep, spam those Google search terms!

However, Blümchen doesn’t attempt to be contemporary, nor even sets its story during the sixties, alongside the novel, but moves things back to the summer of 1956, when rock and roll was causing waves on the far side of the Atlantic; there are several Bill Haley and the Comets songs used. Hence, the arrival of Deborah Collins (Kinski) at St. Clara’s School [the dub says St. Clare’s, but the signs disagree] is a social and cultural timebomb. On the train there, she bumped into Frederick Irving Benjamin Sinclair (Sundquist), known as Fibs from his initials. Conveniently, he is going to St. George’s: that’s the boys’ school standing opposite the bridge leading to St. Clara’s, on its island in a lake. While very scenic, this makes it tough to carry on any kind of relationship, as Deborah soon finds out.

The headmistress thinks Deborah will lick her dubious dorm-mates into shape; they, however, are eager to greet their American cousin, whom they believe will be a trove of worldly wisdom. Deborah is happy to sustain the illusion, and assist them in losing those pesky cherries: “What we all need is a situation where we don’t need to take the initiative,” as one of the girls puts it. The solution: Club Love Unlimited, which will cater to the boys of St. George’s, offering them the chances to enjoy the fruits of St. Clara’s and induct them into the ways of womanhood. Needless to say, the boys are delighted by the prospect. Of course, there’s many a slip ‘twixt cup and lips, and the encounters don’t go as planned. At the end of term, CLU decides to go out of business with a bang, holding a party and striptease contest in the school attic. Bang successfully accomplished, shall we say.

It’s basically a sex comedy, playing like a distaff version of Porky’s, which came out four years later, with teenage boys, desperate to lose their virginities, by any means necessary. Despite the sensational subject matter, the tone is generally kept light, with the encounters usually being foiled with slapstick results. This also has much in common with the “sex report” films that were hugely successful in Germany during the seventies, most obviously the long-running Schulmädchen-Report series, which supposedly exposed the sex lives of teenage girls. Blümchen hits the ground running in this regard, starting off with a close-up of a teenage breast, holding the shot for so long that the shock evaporates, and it then goes beyond erotic, into surreal post-modern territory.

But, man, there’s a lot of lingerie and giggling: I was prepared to swear a pillow-fight was going to break out, at any second. Which would have been fine, as a guilty pleasure, except Jane (Kracht) looks about 12. I kept expecting the police to break down my door simply for having this, even though Kracht was actually born the year after Kinski. It’s an interestingly cosmopolitan selection too, with the five girls from America, Germany and France, and sporting accents to match, at least in the dubbed version. In contrast, all the boys except the Italian nicknamed ‘Plum Pudding’, sport English accents, even “Carlos Rodriguez”. Mind you, the distinction between boys and girls is even clearer in the method of selecting representative. The girls draw cards, for the queen of hearts; the boys eat stuff, either dumplings or live insects. Snips and snails…

But, man, there’s a lot of lingerie and giggling: I was prepared to swear a pillow-fight was going to break out, at any second. Which would have been fine, as a guilty pleasure, except Jane (Kracht) looks about 12. I kept expecting the police to break down my door simply for having this, even though Kracht was actually born the year after Kinski. It’s an interestingly cosmopolitan selection too, with the five girls from America, Germany and France, and sporting accents to match, at least in the dubbed version. In contrast, all the boys except the Italian nicknamed ‘Plum Pudding’, sport English accents, even “Carlos Rodriguez”. Mind you, the distinction between boys and girls is even clearer in the method of selecting representative. The girls draw cards, for the queen of hearts; the boys eat stuff, either dumplings or live insects. Snips and snails…

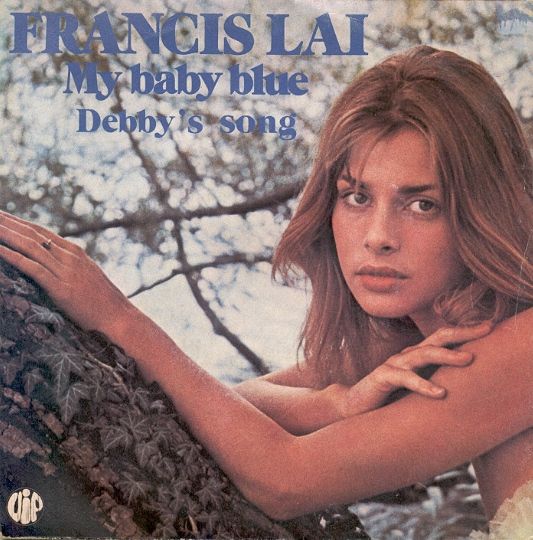

Still, it’s a frothy concoction which manages almost entirely to avoid being sleazy, partly because of its upbeat tone, and partly because both sides are the same age, unlike many of Kinski’s early movies, where she was the subject of attention from much older men. There are some genuinely funny moments – the deadpan safety demonstration before a romantic boat-ride always made me laugh – and the moral of this immoral tale is that there’s someone for everyone, and that true love will find a way. From most accounts, the book has much the same “naively depraved” tone, and what you get here is absolutely a product of its time, shot in focus that’s less soft than fluffy (cinematographer Richard Suzuki also did Emmanuelle), and accompanied by a bouncy score from Oscar-winning composer Francis Lai which you’ll probably find yourself whistling subsequently.

It’s perhaps worth spending a paragraph doing a “where are they now?” on the actors and actresses. Of the boys, Sundquist struggled with depression, and committed suicide in 1993, jumping under a train at a London station. But Sean Chapman, who plays Rodney, had a part in Alan Clarke’s Scum, and is best known (at least, in our household) as ‘Uncle Frank’ in the first two Hellraiser films. Kracht has had a long career in German television, and Gina (Fabiana Udenio) has also kept busy, playing Alotta Fagina in Austin Powers. But perhaps the biggest surprise is Gabrielle Blum, who was head-girl Cordelia, a no-nonsense “jolly hockey sticks” type, who is easily the butchest girl in the entire film. Two years later, she’d win Miss World as Gabriella Brum, albeit resigning after a mere 18 hours wearing the crown.

As for Kinski, she has made no secret of her utter disdain for the movie, saying in an interview, “I’d like to find every copy of that film and burn them.” That’s a bit of an over-reaction. No-one is going to make the mistake of considering this as great art, but there are a lot worse transgressions and embarrassments in the early careers of other actresses. I’m thinking of Jennifer Aniston in Leprechaun bad. Helen Mirren in Caligula bad. This is not even in the same league, and is a film for which I suspect I’ll always have a spot in my film festival of great trash cinema.