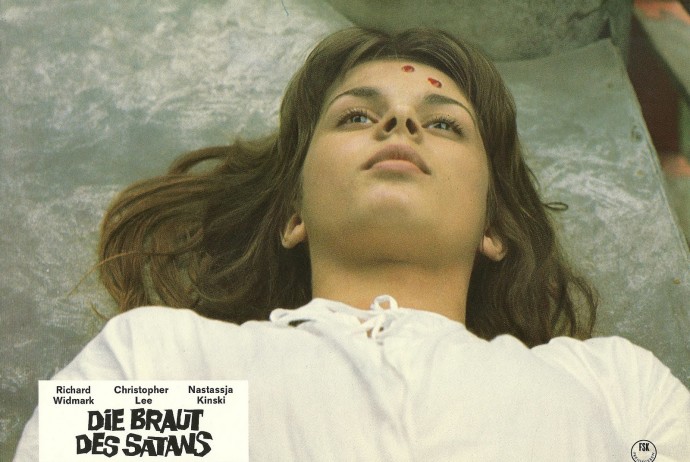

Dir: Peter Sykes

Star: Richard Widmark, Nastassja Kinski, Christopher Lee, Anthony Valentine.

“98% of so-called ‘Satanists’ are nothing but pathetic freaks, who get their kicks out of dancing naked in freezing churchyards. They use the Devil as an excuse for getting some sex. But then, there’s that other 2%…”

— John Verney

The last Hammer horror film ever made, Daughter saw the studio return to the well of Dennis Wheatley, which had previously been drawn from by the company in 1968, with a successful adaptation of The Devil Rides Out. The genre landscape had changed significantly since, most notably with a more explicit style, as seen in The Exorcist and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, and Hammer had been slow to adapt. The early 70’s saw them attempt to inject more sex into their mix, but they also tried their hand at movies based on TV shows, and even co-produced films with the Shaw Brothers in Hong Kong. Describing the success of these efforts as “mixed” would be kind, and Daughter is generally seen these days as the final flicker of a dying candle, though was fairly successful commercially at the time.

You can hear the resonances of various other films present in this. Rosemary’s Baby, released the same year as Rides Out, tells a similar tale of modern Satanism, using an innocent to give birth to the embodiment of Satan. Of course, that was directed by Roman Polanski, who would go on to cast Kinski in Tess. I’m also obviously reminded of The Wicker Man, which also had Christopher Lee as the head of a pagan sect possessing different moral standards. And while this came out a couple of months prior to The Omen, it has a similar manichean struggle between the forces of light and darkness. That’s made most clear in the end caption, by Wheatley: “In light all things thrive and bear fruit… In darkness they decay and die. That is why we must follow the teachings of the lords of light.”

The film starts with the excommunication of Father Michael Rayner (Lee) for his heretical beliefs. 20 years later, Catherine Beddowes (Kinski) is about to leave the German convent where she has lived her whole life, for the annual trip to see her father, just before 18th birthday. But this time, a lot more is being planned than cake and ice-cream, for her parents gave her to Rayner’s Satanic cult, and they’re now looking to cash the IOU, using her as a vessel to return their lord, Astaroth, to the world. However, her father seeks to renege on the deal, enlisting the help of American occult expert John Verney (Widmark). He intercepts Catherine at the airport on her arrival, and there begins a cat-and-mouse game, with Rayner using black magic to recover Catherine, and Verney using his knowledge to fight back.

It’s the performances that make this work, when it does: it’s almost a parade of great British actors, with the most recognizable faces in the supporting cast including Honor Blackman, Frances de la Tour and Brian Wilde. But it’s Lee who dominates the film, with strong performance as a confident and intelligent villains, fully committed to his cause. This is most apparent during a glorious moment, just after the forced birth which is the film’s most squirm-inducing scene (the mother having her ankles and knees tied together, leaving the baby to claw its way out of her stomach). The camera pans across the faces of those in attendance. You see revulsion. Horror. Then Father Rayner, grinning in gleeful abandon. It’s awesome.

In contrast, Widmark comes off as a little flat, and you sense he was included in a sop to the American market, much as the German location and Kinski were to Hammer’s co-producers, Terra Filmkunst GMBH Berlin. One wonders how the latter felt about the portrayal of the Satanists, which on occasion borders on the neo-Nazi. That may be a vestige of Wheatley’s military past – he was gassed at Passchendaele in World War I, and part of a secret planning group called the London Controlling Section in World War II – and the book certainly contains its share of political commentary, mostly anti-Socialist. However, lines like the following could easily be imagined coming from the lips of a Hitler Youth member, as much as a devout nun!

“The youth of the world has lost its way – it’s in a vacuum. They need something to believe in, to follow – something new and powerful. We will provide it, very soon… I simply believe and obey.”

— Catherine Beddowes

In her first English-speaking role, Kinski acquits herself credibly, managing to capture nicely the dual nature of someone who is both completely innocent, as well as being groomed as the embodiment of pure evil and chaos, and fully committed to that end. She has to play both sides of the spectrum, and does so effectively, even though she is delivering her lines in a second language. I’m not sure whether she was dubbed, as Hammer did with a number of their overseas leading ladies, such as Ingrid Pitt in Countess Dracula. It doesn’t sound too different to me from her voice in, say, Reifezeugnis, but I’m not exactly an audio expert, and others have sworn blind her voice was replaced.

What clearly wasn’t replaced was her body, most notoriously when she slides off the sacrificial altar at the end, shedding her robe as Rayner offers her to Verney as a sample of what he could have after Astaroth is re-incarnated. If the topless scenes already in her career were surprising, the full-frontal nudity is even more shocking, considering Kinski was likely 14 at the time of filming. [I recall reading her claim this was a body-double, which hardly seems likely] Equally as creepy is her part in the reverse birth sequence, one of a number of disturbing nightmare sequences, and she has a good dramatic range, going from quiet piety to thrashing around on a bed like a cat in heat. Yes, I accept that I am using a fairly-loose definition of “dramatic range.”

What clearly wasn’t replaced was her body, most notoriously when she slides off the sacrificial altar at the end, shedding her robe as Rayner offers her to Verney as a sample of what he could have after Astaroth is re-incarnated. If the topless scenes already in her career were surprising, the full-frontal nudity is even more shocking, considering Kinski was likely 14 at the time of filming. [I recall reading her claim this was a body-double, which hardly seems likely] Equally as creepy is her part in the reverse birth sequence, one of a number of disturbing nightmare sequences, and she has a good dramatic range, going from quiet piety to thrashing around on a bed like a cat in heat. Yes, I accept that I am using a fairly-loose definition of “dramatic range.”

The film’s real problem is the ending, which appears to demonstrate that the way to defeat ultimate evil is to chuck a rock at it, and takes about two minutes. If it appears to have been made up on the spot, that’s largely because it was. Director Sykes found the original screenplay he was given unusable, leading to an emergency uncredited rewrite by Gerald Vaughan-Hughes, who’d go on to script Ridley Scott’s feature debut, The Duellists. This was still being worked on when shooting started, and it’s really more to the movie’s credit that the results largely work. The climax originally was to have had Rayner struck by lighting, but that was deemed too close to Lee’s fate in Scars of Dracula, leading to an emergency rewrite of the emergency rewrite. Just be grateful it wasn’t all a dream.

The other problem, particularly for a modern viewer, is the film’s attempt to depict the spawn of Satan, something that has not stood the test of time well – though I suspect it probably didn’t look too good in 1976 either. This isn’t a film that needs a physical monster, because Lee does a perfectly good job of embodying evil, in a way that’s more horrific, psychologically, than any puppet creation could be [though, that said, it was only six years later that Rob Bottin’s work on The Thing would prove there are times when showing stuff will beat the pants off letting your imagination do the work]

Random factoids. I used the film as a basis for a D&D adventure while at college. It worked rather well, if I recall. And the film is namechecked in the Simple Minds’ song, Oh Jungleland: they also mentioned Nastassja in their earlier Up on the Catwalk, among the “one thousand names that spring up in my mind.” Neither of these are meaningful in any way.