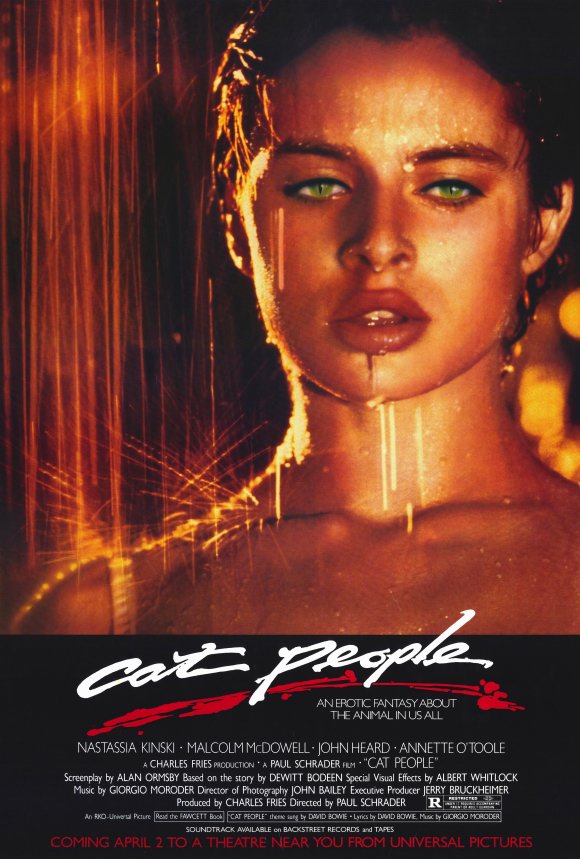

Dir: Paul Schrader

Star: Nastassja Kinski, Malcolm McDowell, John Heard, Annette O’Toole

“Paul, I always fuck my directors. And with you, it was hard.”

— Nastassja Kinski, quoted in Easy Riders, Raging Bulls by Peter Biskind

This will likely be one of the longer entries, because there is so much which can be said about the film: like One From the Heart, its making was an ordeal for many of those involved, and it fared badly at the American box-office. However, time has likely been kinder to this, and critical opinion these days seems more in line with the view expressed by Roger Ebert at the time, when he called it, “a good movie in an old tradition, a fantasy-horror film that takes itself just seriously enough to work,” and that Kinski “never overacts in this movie, never steps wrong, never seems ridiculous; she just steps onscreen and convincingly underplays a leopard.”

It is, of course, a remake of the Val Lewton/Jacques Tourneur film of the same name from the forties. At the time, it was a B-feature for RKO, but has since become regarded as a classic of the genre of understated, lurking horror, that relies on the viewer’s imagination rather than explicit imagery. Of course, a good chunk of that was less conscious choice than simply a product of a much stricter era, with the Hays Code severely limiting what could or could not be shown. However, there’s no denying it was a well-made piece of cinema – though, personally, I prefer Curse of the Cat People for some reason.

It is, of course, a remake of the Val Lewton/Jacques Tourneur film of the same name from the forties. At the time, it was a B-feature for RKO, but has since become regarded as a classic of the genre of understated, lurking horror, that relies on the viewer’s imagination rather than explicit imagery. Of course, a good chunk of that was less conscious choice than simply a product of a much stricter era, with the Hays Code severely limiting what could or could not be shown. However, there’s no denying it was a well-made piece of cinema – though, personally, I prefer Curse of the Cat People for some reason.

My philosophy of remakes is that Hollywood often gets it wrong, because they remake good films, rather than those where there is room for improvement, or where the remakers can bring something new and interesting to the table. For me, the best is probably David Cronenberg’s The Fly, which does both: technically, FX had improved enough to do the concept justice, and Cronenberg brought in a lot of his own sensibilities, with the “body horror” elements for which he was renowned. Another good example is The Thing, which was part of the same desire by Universal to mine their back-catalogue of films. Again, the technical aspects had caught up with the story, and the paranoia John Carpenter added was a great additional dimension.

I’d rate Paul Schrader’s Cat People up there alongside those two. The transformations which were decades in the future for the original could now be shown, even if the work is still short of Rick Baker’s the previous year from American Werewolf. This version takes all the sexual tension that could only be hinted at vaguely in the original, and drags it right out into the open as what Schrader calls a “perverse love story” rather than a horror film. Perverse is certainly the word: between the bestiality, incest and bondage, there is hardly a kink not covered. But it’s also the epitome of the “have sex and die” film: having sex with Kinski will kill you. That could be seen as an early parable for AIDS (first officially acknowledged in LA’s gay community the previous year), but the heavy emphasis on sexuality’s destructive aspects is more likely an offshoot of Schrader’s strict religious upbringing – he didn’t see a film until he was 17. It would have been an interesting contrast to see what the originally-intended director. Roger Vadim, might have done with the material.

This lack of teenage rebellion perhaps explains what could be described as Schrader’s mid-life crisis in the early 80’s. I recall reading somewhere [but can’t locate the source] that he took cocaine virtually every day during the shoot, and then there was also his affair with his leading actress. Somehow, he ended up proposing marriage both to her and his long-term partner, Michelle Rappaport. Kinski broke off the relationship near the end of shooting: he followed her to Paris, where she delivered the devastating burn at the top of this article. As revenge, Schrader threatened to include more full-frontal footage in her in the film, causing Nastassja to run to studio exec Ned Tanen in tears. It wasn’t a tidy break-up.

“It’s not a remake in any fashion, at this point. I think you’d be pretty hard pressed to compare the two films, except indirectly. A remake implies that you’re redoing what has already been done. This Cat People is an update, which means I’m putting the story into a new context.”

— Schrader in Cinefantastique, Vol. 12, No. 4

Listening to Schrader’s commentary on the DVD, he regrets giving it the same title as the original, feeling this burdened the film with too many false expectations – as the above quote makes clear, he doesn’t feel it’s truly a remake at all. Though it has to be said, if he felt that way, then perhaps he shouldn’t have included wholesale, a couple of the most iconic scenes, such as where O’Toole’s character is stalked, first through the city streets, and then in a swimming pool, by Kinski’s jealous were-panther. Or where a woman goes up to Kinski, and greets her as “Mi hermana” – “my sister.” Avoiding those kind of things entirely, could have helped the film establish itself as a truly independent creation, rather than one tied on to the coat-tails of its predecessor.

He does have a point, for the new version is radically different, in a number of ways. The love triangle becomes a love quadrilateral, with Paul (McDowell) bringing his sister Irena (Kinski) to him, completely unaware that her true nature is the same as his. Specifically, whenever they have sex, they change shape, becoming panthers, and the only way to regain human form is to kill someone – typically the person they just had sex with. Before she discovers this, she meets Oliver Yates (Heard), a keeper at the local zoo; their blossoming relationship is a threat not just to Paul’s plans, but to Oliver’s current girlfriend, Alice (O’Toole). When Irena finds out the truth, the cat is certainly let out of the bag.

The film also shifts the setting from New York to New Orleans, which seems a lot more appropriate. The Big Easy is perhaps the most alien of American cities. In many ways, it feels more European than American, and the history of voodoo gives a sense that anything is possible. Schrader, working from a script by Alan Ormsby, also expands the mythos beyond the singular cat person of the original, creating an entire race, apparently originating out of India, with their own back-story. It’s this mythic quality that is among the film’s strongest suits. The original Irena felt more like a woman with a unique problem, rather than one member of a race living below the notice of normal humanity. There was originally more of this, with a sequence where Irena spoke to a half-panther/half-woman (played by her real mother, Bridgit Kinski), cut from the finished film.

You can also see elements of the Dante & Beatrice story in the Oliver/Irena relationship, which can never be happily consummated. This is explicitly referenced in a bust of Beatrice, and the poem by Dante which Oliver is reading just before he meets Irena, and the character does seem, to a certain extent, to be a projection of Schrader’s character: a shy intellectual, who distances himself from the human world, until he finds someone to whom he is prepared to commit whole-heartedly. There’s an oddly-pointless scene on the bus where a man – looking not dissimilar to the director – stares at Irena, and I note the presence on Oliver’s bedside of a book of poems by Yukio Mishima. Schrader would subsequently go on to direct a biographical feature about the Japanese writer and nationalist.

“She had to be beautiful in a nonregional, non-specific way. She had to be ethereal. She had to be totally credible as a virgin, because it is crucial to the piece, not just a plot point. She had to be twenty or able to play girlish. She had to be willing to do nudity, and she had to be able to act. Now that was a real fistful of qualifications. We looked at a lot of people, but there was never anyone else who hit six for six.”

— Schrader in American Film, April 1982.

Another strength comes from McDowell and Kinski as the leads. Both are incredibly feline, in both looks and action, and it’s impeccable casting. Witness Irena springing to her haunches on the bed, when her brothers startles her by crashing through the window, or McDowell patting the bed to encourage her to join him there. It’s little moments like that which succeed in convincing you they are capable of turning into panthers [as an aside, the animals used in the movie were actually a mix of the genuine thing, with leopards and mountain lions dyed black!]. Kinski has a raw, untapped sensuality, and it’s easy to see why the film arranged its production schedule around her availability: “No-one else came close,” said Schrader. As her brother, McDowell exemplifies the dark side, possessing a natural cruelness, like a cat that toys with a mouse rather than killing it, because it genuinely doesn’t know any better.

On the technical side, the two aspects which particularly stand out are the design and the soundtrack. The former is largely the work of Ferdinando Scarfiotti, who was credited as a “visual consultant,” for union-related reasons, but basically oversaw every aspect of the look and feel of the movie. It’s truly a treat for the eyeballs, with a marvellous palate of colours, and it’s easy to see why Scarfiotti would eventually go on to win a Best Art Direction Oscar, for The Last Emperor. Giorgio Moroder’s synth-driven music is also perfect – and one of the few soundtracks I will listen to, entirely separate from the movie, peaking with David Bowie’s title song. It’s fitting, as there are some overlaps between this movie and The Hunger, both sharing the elements of sex, death and Bowie.

On the technical side, the two aspects which particularly stand out are the design and the soundtrack. The former is largely the work of Ferdinando Scarfiotti, who was credited as a “visual consultant,” for union-related reasons, but basically oversaw every aspect of the look and feel of the movie. It’s truly a treat for the eyeballs, with a marvellous palate of colours, and it’s easy to see why Scarfiotti would eventually go on to win a Best Art Direction Oscar, for The Last Emperor. Giorgio Moroder’s synth-driven music is also perfect – and one of the few soundtracks I will listen to, entirely separate from the movie, peaking with David Bowie’s title song. It’s fitting, as there are some overlaps between this movie and The Hunger, both sharing the elements of sex, death and Bowie.

It’s not a perfect movie, by any means. There are logical flaws: when Alice is being menaced in the pool, it’s implied that it’s by Irena in panther form. However, that would imply she both had sex with someone, and then killed, to return to her human form, and there’s no evidence presented for either. “Look, this is a fantasy film,” an apparently-grumpy Schrader told Cinefantastique when questioned about it. “If you really need an explanation, it’s Kinski making cat sounds.” Okay… The pacing is also odd, the main antagonist departing the film with half an hour left, and taking with him a large part of the dramatic impetus. As noted, the transformation scenes haven’t stood the test of time well, and Schrader’s use of reverse-motion (partly a homage to Jean Cocteau) works with what could kindly be called variable success.

The audience definitely didn’t respond well: at the US box office, it recouped only about one-third of its production costs, and Schrader’s career never really recovered. There was another high-profile failure when his Exorcist prequel was entirely re-shot by Renny Harlin, and he was last seen funding a project starring Lindsay Lohan on Kickstarter, which went about as well as you would expect. Still, the bottom line is that Schrader dared to do something different: even now, over 30 years later, there still hasn’t been another film quite like it, and for all its flaws, can only be admired as such.

“The day it opened at the Avco Theater on Wilshire Boulevard in Westwood, Jerry Bruckheimer and I went to the first evening screening and we sat in the back – there were a couple of teenage girls in front of us. When it came to the bondage scene, when Oliver is tying the naked Irena to the bed, so that he can screw her back into being a leopard, and David Bowie is singing all this primitive religious music, one girl turned to the other, put her hand over her mouth and said, “Oh, my God…” And I turned to Jerry and said, “I think maybe we went too far…” I love the fact that we went too far.”

— Schrader, on the DVD commentary