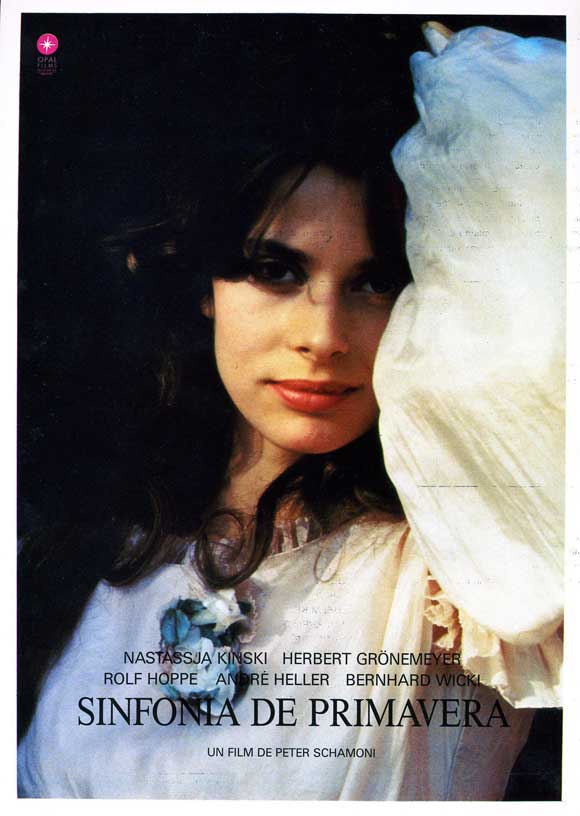

Dir: Peter Schamoni

Star: Herbert Gronemeyer, Nastassja Kinski, Rolf Hoppe

a.k.a. Spring Symphony

“I’ve been taking lessons for a year or so and every time I hear a piano playing, it goes through and through me, so I’m going to buy a little piano.”

— Nastassja Kinski

I don’t know where that quote comes from – it appears online only in various quote databases! – or what it refers to, but it seems appropriate to drop it in at the start of this review, covering as it does a film where she plays Clara Wieck, one of the most celebrated pianists of the 1800’s. She was a child prodigy, who toured not only her native Germany, but much of continental Europe, accompanied by her father (Hoppe), a piano salesman and teacher who realizes her artistic talent far outstrips his more prosaic business skills. He also takes on board another young pianist and composer, Robert Schumann (Gronemeyer), only to find that as his daughter matures into womanhood, controlling her becomes increasingly more difficult. She falls in love with Schumann, despite Herr Wieck’s best efforts to keep them apart (physically and emotionally), culminating in a courtroom face-off, where the couple try to force him to assent to their marriage.

I don’t know where that quote comes from – it appears online only in various quote databases! – or what it refers to, but it seems appropriate to drop it in at the start of this review, covering as it does a film where she plays Clara Wieck, one of the most celebrated pianists of the 1800’s. She was a child prodigy, who toured not only her native Germany, but much of continental Europe, accompanied by her father (Hoppe), a piano salesman and teacher who realizes her artistic talent far outstrips his more prosaic business skills. He also takes on board another young pianist and composer, Robert Schumann (Gronemeyer), only to find that as his daughter matures into womanhood, controlling her becomes increasingly more difficult. She falls in love with Schumann, despite Herr Wieck’s best efforts to keep them apart (physically and emotionally), culminating in a courtroom face-off, where the couple try to force him to assent to their marriage.

It’s interesting, in the light of Klaus’s subsequent biopic of Paganini, that the film starts off with a scene where Schumann watches the maestro violinist perform, and vows to become the Paganini of the piano. It doesn’t happen, for a variety of reasons, such as an ailment with his hand, which the film suggests was the result of over-taxing it while training – though an alternative theory suggests it was a side-effect of syphilis medication. This is not exactly rejected here, as the film doesn’t shy away from the apparent fact that, while hanging around town, waiting for Clara to come back from tour, Robert wasn’t exactly faithful. While this may be historically accurate, it doesn’t exactly enhance the audience’s perception of him as a nice guy, or someone whom we want to see find true love and happiness. The same goes for his rapid dumping of an earlier prospective wife, when he discovers she won’t get a dowry.

It’s an odd kinda love story in general. The couple don’t spend much time together, so you don’t get a great deal of sense that they’re developing any affection for each other. While the age gap between them wasn’t that much – only nine years – it’s also kinda odd that when they first meet, he’s about 20 and she’s eleven. Mind you, as shown in the still below, Clara’s relationship with her dad also seems more than a little creepy at times too; art imitating life again there?. Even though it’s clear he is devoted to her, and only acting in what he genuinely believes to be her best interests. Herr Wieck definitely falls into the category of “controlling father,” and Clara’s struggle for independence from him – emotional and spiritual as well as legal – is among the more interesting aspects of the movie. It certainly seems that her father cares about her rather more than Robert does.

Another problem is that it stops so suddenly, with their wedding, that it almost seems as is Schamoni ran out of money. There’s a brief post-script outlining the rest of their lives, but the film almost makes it feel like marriage is the end of the important bit of their lives, and that certainly isn’t the case. Schumann would live on for another 16 years, before dying in an insane asylum. Clara, meanwhile, had eight kids, though she outlived half of them, and it’s a shame the film didn’t include later incidents, like the one during the an 1849 uprising in Dresden, when she walked through the front lines, defying a pack of armed men who confronted her, rescued her children, then walked back out of the city through the dangerous areas again. That, alone, seems more dramatic than anything this flavorless Europudding has to offer. [Their post-marriage life is covered more in another film, 2008’s Geliebte Clara. The pair’s story was also told in Song of Love, made in 1947, and with Katherine Hepburn playing Clara]

However, one thing was undeniably impressive. I’m used to the usual practice of depicting classical music in films: shots of your actors faking it. with any actual playing carefully located out of view, and inter-cut this with hands of actual musicians doing their thing. This often adopts the same approach, though Gronemeyer had been playing piano since he was eight (and is better known in Germany, particularly these days, as a musician – his 2002 album, Mensch, remains the all-time biggest seller there). But then, there are times when it’s clearly all Kinski, and I’ll be damned, if the girl doesn’t nail it, her hands flying over the keyboard like a pair of highly-caffeinated butterflies. Generally, the music here is a treat, both for the eyes and ears.

On the one hand, it’s nice to see a film which doesn’t play exclusively on Kinski’s sex-appeal – which, to be honest, much of her early output tended to do. Even if there’s still a strong overtone of Daddy issues to be found here, it’s also the struggle of a strong-minded young woman for her life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. However, there’s just too much here which is painfully obvious: the Paganini scene which opens things. is followed by students dueling with swords, and then raucously drinking beer out of steins in a bar while singing about “der Vaterland.” Yes, we get it: this is supposed to be Germany, as if we didn’t get a clue from the whole “speaking in German” thing. There’s no shortage of symphonics to be found here, but the film is in desperate need of some additional spring.