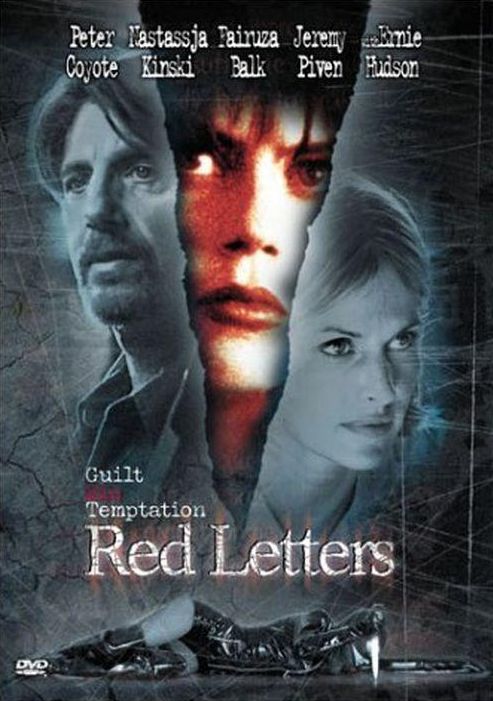

Dir: Bradley Battersby

Star: Peter Coyote, Nastassja Kinski, Fairuza Balk, Jeremy Piven

Back in the nineties, there was a short-lived magazine, I think published by Hustler, called Prison Babes, to which I may or may not have had a subscription. It was a weird, yet oddly compelling mix of pornography and true crime; unsurprisingly, it lasted only a few issues before folding. I hadn’t thought about it in years, but seeing Nastassja playing a convict here reminded me of it for some reason – even if this is quite some distance from the typical “women in prison” genre, lacking in predatory lesbians, sadistic wardens or any form of rioting. More’s the pity, perhaps.

Instead, we have college English professor Dennis Burke (Coyote), who is forced to find new employment after a disgruntled student divulges their educationally inappropriate relationship, and heads cross country to another school prepared to offer him a second chance. While his specialty is 19th-century author Nathaniel Hawthorne, Burke’s fame is significantly more due to a cult erotic novel he wrote a couple of decades previously, before his wife’s death, and this leads to much temptation for the lecturer, particularly coming in the shape of the dean’s daughter, Gretchen (Balk).

While handling mail sent to his apartment’s previous resident, he discovers some very frank and personal letters from Lydia (Kinski). who turns out to be writing from prison where she is serving a sentence after being convicted of killing the wife of her lover – Lydia claims she was framed by her lover, who was the actual killer. Their relationship blossoms for a while but takes a sour turn, and Lydia then turns her attention to Dennis’s friend, Thurston Clarque (Piven), another teacher and unrepentant hacker. Her interest is not romantic; instead, she uses her sister to seduce Clarque into adjusting the prison records so Lydia is sent to the infirmary, from where she is able to make her escape.

Which is really where the film falls apart. To this point, it has been an interestingly noir-ish thriller with erotic overtones, and you wonder where it might go in the second half. Unfortunately, it descends into plot convulsions more appropriate to a bedroom farce from the “Whoops! Where are my trousers?” genre, Burke charging around, in ever-decreasing circles, as he tries to stop the dean from finding out about Gretchen, and the cops from finding out that Lydia is hiding in his apartment. Few things signify the seismic shift in tone more dramatically than the presence of Pauly Shore, in an uncredited cameo as the previous occupant. Though in the film’s defense, we also get Udo Kier as Lydia’s ex-lover, always a pleasure, even if his role is about as significant as Shore’s.

Director Battersby has been responsible for five feature films – all of which also had scripts written by Battersby. This is probably a warning in itself; at least Quentin Tarantino can get other people to make his scripts occasionally – and the results are often the better for it, as we see in True Romance and From Dusk Till Dawn. Director Battersby really needed to have a stern talk with writer Battersby, and send the script back to himself with some strongly-worded rewrite instructions, because the further this drifts on, the more disconnected and implausible it becomes. There appears to be a stunning ignorance for how the law actually works, for example: cops do not casually give suspects 48 hours to solve cases, and federal charges for helping someone escape from custody do not magically evaporate, just because they were wrongly convicted.

Director Battersby has been responsible for five feature films – all of which also had scripts written by Battersby. This is probably a warning in itself; at least Quentin Tarantino can get other people to make his scripts occasionally – and the results are often the better for it, as we see in True Romance and From Dusk Till Dawn. Director Battersby really needed to have a stern talk with writer Battersby, and send the script back to himself with some strongly-worded rewrite instructions, because the further this drifts on, the more disconnected and implausible it becomes. There appears to be a stunning ignorance for how the law actually works, for example: cops do not casually give suspects 48 hours to solve cases, and federal charges for helping someone escape from custody do not magically evaporate, just because they were wrongly convicted.

There are a number of other aspects which seem poorly considered or under-written. At one stage, for example, a big fuss is made over Burke’s decision to give a minority student a C grade, until the dean over-rules him. Is there a point to this? If any such exists, it completely went over my head. Never mind the lack of purpose, I’m not even sure if Battersby is saying such affirmative action is a good or a bad thing. However, it’s the unevenness of tone which is the film’s biggest flaw. The film starts, f’heavens sake, with a naked co-ed sitting on Burke’s desk, reading to him from his book – then goes all coyly PG-rated for the rest of the film, even though Lydia’s sister is played by Miss October 1997 from Playboy, Layla Roberts. I’m hard pushed to imagine Battersby hired Roberts for her acting talent.

We’ve discussed previously Kinski’s weakness as far as comedic performances go, and much the same could be said for Coyote, who is by no means a bad actor overall. The first half of this is fine, when he’s in more dramatic territory; any middle-aged man will likely empathize with Dennis’s struggle to avoid the fleshly temptations offered by Gretchen and her friends. It’s when the lighter aspects kick on, and he’s expected to carry the humor of the film, that he falls woefully short. There are way too many sequences that are obviously intended to be funny, yet fail miserably on that score, even with help from veterans like Ernie Hudson, as the detective who put Lydia away and is now investigating her escape. Hard to be sure if the blame goes to the script or Coyote; I’m inclined to think both deserve their share.

Kinski, at least, isn’t required to try for laughs, and by far the worst thing about her portrayal is the really terrible black wig Lydia wears after she has supposedly “dyed her hair” to aid with her escape. It looks like something from the clearance aisle at a down-market party store. She’s at her best when we see her during Dennis’s first visit to her in jail, gazing up at him from under her hair, with those eyes, in a manner – either consciously or unconsciously – calculated to entice. Burke’s subsequent willingness to go to any extreme to help her is entirely credible, and it’s just a shame the other aspects of the plot possess nowhere near as much credibility.

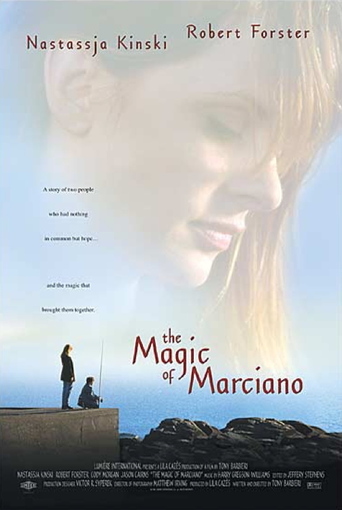

James uses his imagination as an outlet from the rough world which he inhabits, such as riffing off an ancestor – the Marciano of the title – who was a diplomat, but is elevated to the King of Italy in the boy’s mind! Though this also takes him down some dark paths, most notably, the sequence where he fantasizes about shooting Curt with the gun he finds in his mother’s drawer. [As an aside: mental illness and firearms are never a good combination…] I’d perhaps like to have seen that aspect drawn out and explored more, not least because James has a good deal from which to escape. His generally upbeat and optimistic nature is in stark contrast to the intensely bipolar personality of Katie, who can flick from loving mother to scary, scary person in an instant. Mind you, her history – not least with regard to her son – appears to be a sad saga in itself, and she’s never other than someone for whom you feel sympathetic.

James uses his imagination as an outlet from the rough world which he inhabits, such as riffing off an ancestor – the Marciano of the title – who was a diplomat, but is elevated to the King of Italy in the boy’s mind! Though this also takes him down some dark paths, most notably, the sequence where he fantasizes about shooting Curt with the gun he finds in his mother’s drawer. [As an aside: mental illness and firearms are never a good combination…] I’d perhaps like to have seen that aspect drawn out and explored more, not least because James has a good deal from which to escape. His generally upbeat and optimistic nature is in stark contrast to the intensely bipolar personality of Katie, who can flick from loving mother to scary, scary person in an instant. Mind you, her history – not least with regard to her son – appears to be a sad saga in itself, and she’s never other than someone for whom you feel sympathetic.