Dir: Willard Carroll

Star: Gillian Anderson, Ellen Burstyn, Sean Connery, Nastassja Kinski (uncredited)

The film admits the difficulty of what it’s trying to accomplish in the opening monologue, given by Angelina Jolie’s character, the punky extrovert Joan: “Talking about love,” she concludes, “Is like dancing about architecture.” [The latter provided the film’s original title, when it was playing the festival circuit] The film then spends the next two hours doing exactly that: talking about love. It’s certainly a challenging task, but the film approaches it from a plethora of different angles, which is probably a wise move: you may not find all of them interesting or relevant, but the odds are that a number will resonate with your personal experiences in some way. Much credit, I think, to Carroll for the script he also wrote, which does an exceptionally fine job of keeping its numerous balls in the air, and switching between them without losing narrative coherence, before bringing them all together for the final scene.

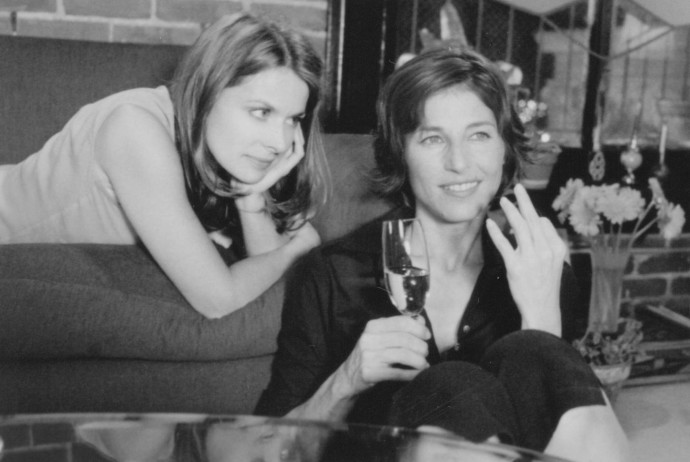

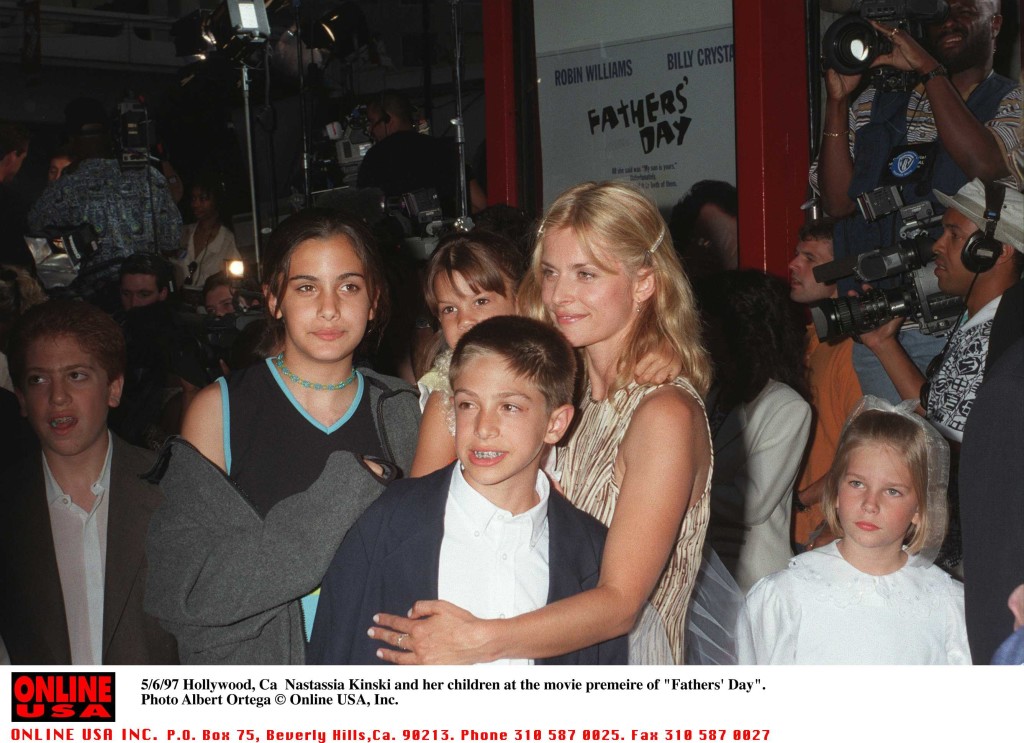

To get the (low) Kinski contribution out of the way before embarking on a more general coverage of the movie, she plays a lawyer who crosses paths in an upscale bar with Hugh (Dennis Quaid). He spins her a story about being a TV executive, whose wife and children have just left him, and whose life had revolved around a failed effort to revitalize the Thursday night schedule for his network. Which is odd, because the last time we saw him, he was in a different bar, spinning an entirely different tale of woe to another woman, about how he killed his wife and child in a car-accident. Hmmm. Odder still, the same lady who was watching in the bar there, is now also watching him here. Hugh then moves on to a drag bar, and tells a third different saga there. What the heck is going on?

There is actually a solid enough explanation, though to be honest, it perhaps backfires a bit, since it casts more than a little doubt on the emotional honesty of everyone else. That impairs the effectiveness, since the audience needs to buy into these characters, rather than be wary of them. I think Carroll is perhaps being over cautious and hedging his bets, as with the opening monologue, basically apologizing for the rest of the film. He needs to be more confident in his characters and the script and performances abilities to make them interesting. Indeed, the sheer volume of different angles also perhaps suggests something similar, along the lines of, “Don’t like these characters? Wait, wait – there’ll be some other ones along in just a minute!” And that isn’t actually the case, because the majority have something interesting to say.

Which ones work, however, is almost entirely subjective, since as already noted, some will be closer in line with your own thoughts, expectations and romantic history. Interestingly though, despite the drag queen’s presence, it is entirely about male-female relationships. There is one guy who is dying of AIDS, but that one is focused on his relationship with his mother [As an aside, what was it with Kinski and movies in which people get AIDS? I lived in London for the entirety of the nineties, and as far as I am aware, never knew anyone who was even HIV positive. Yet her characters appear to share movies with them frequently. Guess I was just moving in the wrong circles. Or, possibly, this is a case of film makers liking to make a drama out of a topical crisis, especially one affecting many people in its own house.]

Which ones work, however, is almost entirely subjective, since as already noted, some will be closer in line with your own thoughts, expectations and romantic history. Interestingly though, despite the drag queen’s presence, it is entirely about male-female relationships. There is one guy who is dying of AIDS, but that one is focused on his relationship with his mother [As an aside, what was it with Kinski and movies in which people get AIDS? I lived in London for the entirety of the nineties, and as far as I am aware, never knew anyone who was even HIV positive. Yet her characters appear to share movies with them frequently. Guess I was just moving in the wrong circles. Or, possibly, this is a case of film makers liking to make a drama out of a topical crisis, especially one affecting many people in its own house.]

Personally, the pairing which I liked best – and which I would have been happy to see as the focus of a standalone feature – was Paul (Connery) and Hannah (Gena Rowlands). They have just received some devastating news of their own, but Paul insists that life goes on, exactly as before. Their relationship is one born of decades of familiarity with each other. It’s not perfect, and has static – there is clear indication of that, based on simmering resentment over an incident a couple of decades ago- but no relationship ever is, and they clearly do love each other very, very much. That’s clear when they exchange vows during their marriage renewal ceremony at the end, having been told to come up with one sentence to sum up their relationship.

Hannah: “You are the tenant of my heart: often behind in the rent, but impossible to evict.”

Paul: “If I had to do it all over again, I wouldn’t do it any different.”

I’ve been married for 14 years now, and I wouldn’t do it any different either: I hope that remains the case when I become Connery’s age then, in another 14!

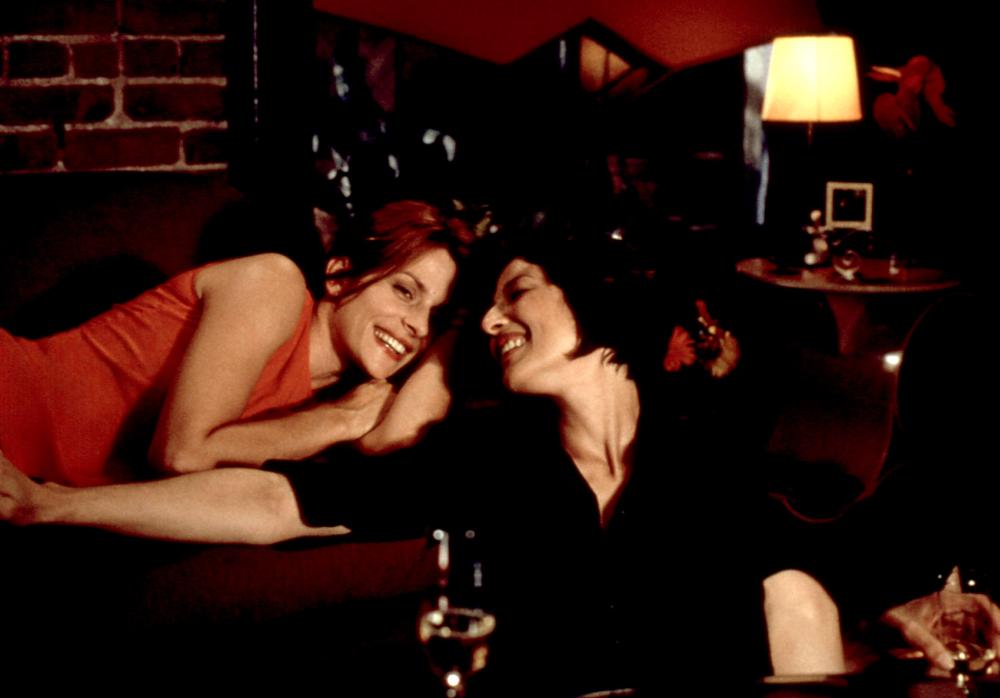

That is just one of the range of stories present here. Other run the gamut from the young and photogenic, such as Jolie and Ryan Phillipe’s tale of damaged people finding each other, through a married woman (Madeleine Stowe) having an affair with a man (Anthony Edwards) for purely physical reasons, only for him to want more, on to the previously mentioned thread about a mother (Burstyn) and hers AIDS-stricken son (Jay Mohr). It certainly qualifies as looking to have something for everything, and I think it works, though it’s arguably rather too talky – most people I know would rather gnaw their own limbs off than talk about their feelings, or worse still, listen to someone else do so. But, hey, I’m British, so what do I know? Much credit is due to Carroll for putting together one hell of a cast, even including Jon Stewart, in a rare “acting” role; given this was only the director’s second movie, I’m nor sure how he managed that, though he does seem to have been in the business, mostly as a producer for a lot longer.

Kinski’s brief presence, while welcome, is odd because it’s entirely uncredited, and I’ve not been able to shed any light on the reason why, or how she became involved in the project either. No matter, for after the previous couple of entries, it’s a refreshingly warm look at human nature and behavior, rather than trying to rub our noses in the grubbier side of relationships and the actions they provoke.