Dir: Wim Wenders

Star: Otto Sander, Horst Buchholz, Willem Dafoe, Nastassja Kinski

You, whom we love, you do not see us, you do not hear us.

You imagine us in the far distance, yet we are so near.

We are messengers, who bring closeness to those who are distant.

We are messengers, who bring the light to those who are in darkness.

We are messengers, who bring the word to those who question.

We are neither the light, nor the message.

We are the messengers. We are nothing. You are, for us, everything.

— Opening voice-over

Kinski hasn’t appeared in many sequels. I’m not sure if this is a conscious choice, or one dictated for her by the market – there didn’t appear to be much demand for Revolution 2. This was a rare, perhaps unique, exception, her third collaboration with Wenders being a sequel to Wings of Desire from six years earlier. It’s not as highly regarded generally: by IMDb rating, Wings is #3 of the 42 titles for which Wenders received a directorial credit, while Faraway comes in at #10, though the 7.3 grade for the latter is still one many directors would kill for. [It’s also the lowest of the three Kinski films, with Paris, Texas at #2] The main criticism appears to be Wenders’ efforts to bolt aspects of a thriller onto a more contemplative approach. It just isn’t a genre with which he seems comfortable, either writing or directing.

The star is Cassiel (Sander), an angel who roams the streets and skies of Berlin, listening in on humanity’s troubles, yet still yearns to experience all life has to offer. After he intervenes to save a child falling from a balcony, he loses his wings, and is helped by another former angel, Daniel (Bruno Ganz) – now a pizza-maker, he was previously an angel too, whose transformation into a human was the main focus of Wings. Cassiel still struggles to come to terms with the more earthy aspects of life, and unwittingly falls in with shady gangster Tony Baker (Buchholz), not knowing that Baker’s business involves trading bootleg porn for guns. Shocked when he discovers this, Cassiel vows to destroy Baker’s facility, with the help of a group of circus performers and Colombo. Yep, Peter Falk. I’ll get back to him in a bit. However, a rival of Baker hijacks their barge, taking hostage both Cassiel’s friends and the girl whose rescue ended his divine status.

Kinski plays Raphaela, an angel who remains in that form, so serves a similar purpose to the film, as the one Cassiel did in Wings. She is just one of a selection of supporting characters who populate the fringes of the movie, and damn, she looks the part with a pair of wings, almost as much as another Euro-starlet, Emmanuelle Beart, did in Date With an Angel. If Raphaela serves no real purpose except giving Nastassja that once per decade paycheck from Wenders, her mere presence is enough to justify the character’s existence. She’s a good deal less jarring than some of the others, notably Dafoe as “Emit Flesti”, which is one of those names which is nowhere near as clever as Wenders thinks it is, there solely to push events along as necessary – or bring them to a grinding halt, at one point. There’s also Lou Reed, who shows up, for little or no reason. Peter Falk also seems incongruous, both playing himself as an artist, and playing himself playing Colombo, though he played himself in Wings as well, where it was revealed he too was a former angel.

Kinski plays Raphaela, an angel who remains in that form, so serves a similar purpose to the film, as the one Cassiel did in Wings. She is just one of a selection of supporting characters who populate the fringes of the movie, and damn, she looks the part with a pair of wings, almost as much as another Euro-starlet, Emmanuelle Beart, did in Date With an Angel. If Raphaela serves no real purpose except giving Nastassja that once per decade paycheck from Wenders, her mere presence is enough to justify the character’s existence. She’s a good deal less jarring than some of the others, notably Dafoe as “Emit Flesti”, which is one of those names which is nowhere near as clever as Wenders thinks it is, there solely to push events along as necessary – or bring them to a grinding halt, at one point. There’s also Lou Reed, who shows up, for little or no reason. Peter Falk also seems incongruous, both playing himself as an artist, and playing himself playing Colombo, though he played himself in Wings as well, where it was revealed he too was a former angel.

Easily the worst of all is Mikhail Gorbachev, who sits in a hotel room, observed by Cassiel, burbling cod philosophy about how “A secure world can’t be built on blood, only on harmony.” Coming from the former President of the Soviet Union, that’s more than faintly ludicrous. Oh, I get what Wenders was aiming for: between Wings and Faraway, the Berlin Wall had come down and Germany reunited, after 40 years of the Cold War, and the resulting uncertainty and spiritual chaos was clearly a major influence on him. Charitably, it probably had more cultural resonance at the time. But two decades later, Gorbachev’s presence now seems like little more than stunt casting of the highest order, and badly dated at that. Though I’d expect little else from the only former Russian President ever to appear in a commercial for Pizza Hut. Can’t see Joe Stalin doing that, somehow. Hell, or even Vladimir Putin.

It’s a mix of the transcendentally beautiful and philosophical, with the laughably pretentious, overblown and ludicrous. The opening shot is simply one of the best in all cinema, telescoping out to swirl and circle round the 200-foot tall Berlin Victory Column, with its angel statue on the top – on whose shoulder, Cassiel is perched. As in Wings, the film switches between black and white, for the angels’ perspective, and color for the human point of view, and the transitions are often breathtaking in their impact. The movie is generally at its best when there’s nothing much happening: Cassiel wandering the city, either listening in on the inhabitants’ thoughts, or after his transformation, coming to terms with being human, and all that entails, both good (the ability to enjoy a stuffed olive) and bad (it appears former angels have a weakness for hard liquor, and unfortunately little tolerance for it). And Sander is perfect for the role, his face capturing both the innocence and wisdom you would imagine such a character having.

It’s a mix of the transcendentally beautiful and philosophical, with the laughably pretentious, overblown and ludicrous. The opening shot is simply one of the best in all cinema, telescoping out to swirl and circle round the 200-foot tall Berlin Victory Column, with its angel statue on the top – on whose shoulder, Cassiel is perched. As in Wings, the film switches between black and white, for the angels’ perspective, and color for the human point of view, and the transitions are often breathtaking in their impact. The movie is generally at its best when there’s nothing much happening: Cassiel wandering the city, either listening in on the inhabitants’ thoughts, or after his transformation, coming to terms with being human, and all that entails, both good (the ability to enjoy a stuffed olive) and bad (it appears former angels have a weakness for hard liquor, and unfortunately little tolerance for it). And Sander is perfect for the role, his face capturing both the innocence and wisdom you would imagine such a character having.

But, oh dear… The more worldly aspects are just terrible, completely implausible and feeling like they strayed in from a bad pastiche of a Coen Brothers film. Witness the witless scene were Cassiel and Baker are held at gunpoint by Baker’s rival, who has Baker’s feet in a bucket of cement and is waiting by the side of a canal, for it to harden. Cassiel’s flailings somehow knock the rival into the canal, and his minions squawk about like headless chickens. It’s more or less impossible to take anyone seriously as a threat after that point, and that’s before we get to the bumbling security guards, talked by Colombo into searching for a non-existent contact lens and pretending to sleep. It’s such a sharp contrast to the more thoughtful and spiritual aspects, you are left to wonder if Wenders allowed a nine-year-old child to handle these sections of the script, and they completely destroy the atmosphere which had been lovingly created. A far greater consistency of tone is the main reason why Wings of Desire is the better movie.

Things perk up a bit for the finale, though you do have to suspend your disbelief significantly. Milan is not exactly a small city, and one can presume its airport is similarly-sized. But the three protagonists here miraculously arrive at the same place at the same time, as if this was a one-gate facility in rural Montana. They then whizz off down a highway which is also so completely deserted, you wonder if the rapture had occurred. There’s not even anyone to be seen, driving past on a moped going “Ciao!” [Bonus point to you if you get that reference] Well, right up until the end, when the 16-wheeler necessary to the plot suddenly appears, like a diesel-powered deus ex machina, to tidy up the loose ends, and do what Tommaso apparently is unable to. As an aside, should mention on the copy I was watching, the audio was significantly out of sync with the video. For most of the film, that didn’t matter, because it was subtitled anyway, so that was in sync. But during the action finale, you’d have Nastassja apparently screaming her lungs out, with nothing to be heard, save the roar of the engines. It actually added a kinda surreal beauty to proceedings, like a waking nightmare.

Things perk up a bit for the finale, though you do have to suspend your disbelief significantly. Milan is not exactly a small city, and one can presume its airport is similarly-sized. But the three protagonists here miraculously arrive at the same place at the same time, as if this was a one-gate facility in rural Montana. They then whizz off down a highway which is also so completely deserted, you wonder if the rapture had occurred. There’s not even anyone to be seen, driving past on a moped going “Ciao!” [Bonus point to you if you get that reference] Well, right up until the end, when the 16-wheeler necessary to the plot suddenly appears, like a diesel-powered deus ex machina, to tidy up the loose ends, and do what Tommaso apparently is unable to. As an aside, should mention on the copy I was watching, the audio was significantly out of sync with the video. For most of the film, that didn’t matter, because it was subtitled anyway, so that was in sync. But during the action finale, you’d have Nastassja apparently screaming her lungs out, with nothing to be heard, save the roar of the engines. It actually added a kinda surreal beauty to proceedings, like a waking nightmare.

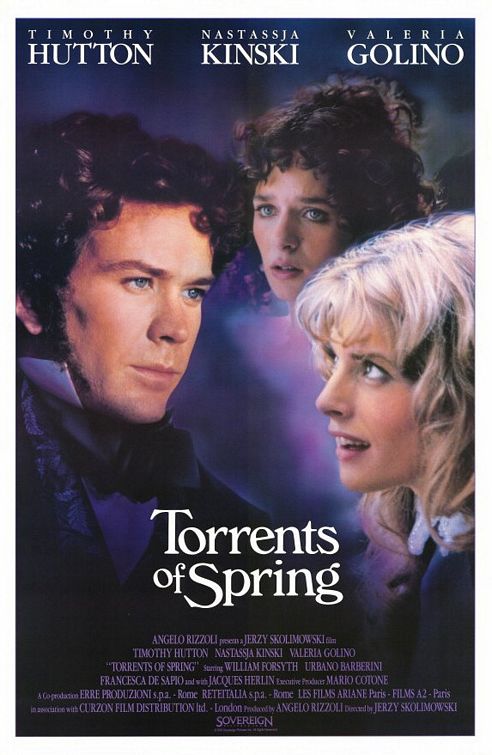

In particular, she aims at his relationship with Gemma Rosselli (Golino), who works in a pastry-shop in the German town Mainz, which Sanin is visiting. He saves the live of her brother, is invited to dinner, and the two fall in love. Which is unfortunate, since she is already engaged. However, when Dmitri shows himself willing to fight a duel to protect Gemma’s honor (even though the incident was actually provoked by Maria), she breaks the relationship off, and Dmitri begins preparing to sell his Russian estates and move permanently to Mainz. He bumps into an old friend, Prince Ippolito Polozov (Forsythe), who says his wife may be interested in purchasing Dmitri’s land – but this is merely a ruse for Maria to get up close and personal with our hero. She reels Dimiri in, seduces him, then invites Gemma over, for what rapidly becomes a credible candidate for Most Uncomfortable Dinner Party Ever.

In particular, she aims at his relationship with Gemma Rosselli (Golino), who works in a pastry-shop in the German town Mainz, which Sanin is visiting. He saves the live of her brother, is invited to dinner, and the two fall in love. Which is unfortunate, since she is already engaged. However, when Dmitri shows himself willing to fight a duel to protect Gemma’s honor (even though the incident was actually provoked by Maria), she breaks the relationship off, and Dmitri begins preparing to sell his Russian estates and move permanently to Mainz. He bumps into an old friend, Prince Ippolito Polozov (Forsythe), who says his wife may be interested in purchasing Dmitri’s land – but this is merely a ruse for Maria to get up close and personal with our hero. She reels Dimiri in, seduces him, then invites Gemma over, for what rapidly becomes a credible candidate for Most Uncomfortable Dinner Party Ever.

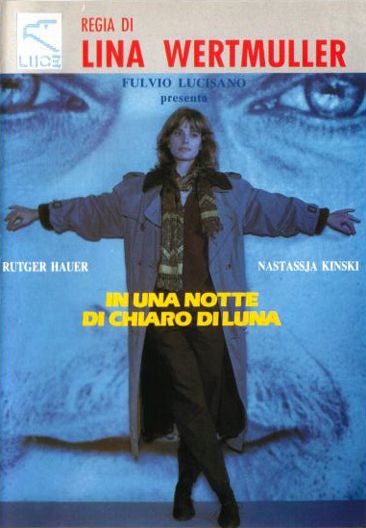

So, the moral of the story is, it’s perfectly alright to drug and abduct a woman that takes your fancy, because if you’re nice to her, she’ll end up falling in love with you – though “Stockholm syndrome” would perhaps seem a more credible explanation. Man, I’d have got laid so much, if only I’d known that in the eighties. Okay: known that,

So, the moral of the story is, it’s perfectly alright to drug and abduct a woman that takes your fancy, because if you’re nice to her, she’ll end up falling in love with you – though “Stockholm syndrome” would perhaps seem a more credible explanation. Man, I’d have got laid so much, if only I’d known that in the eighties. Okay: known that,