Dir: James Toback

Star: Nastassja Kinski, Rudolf Nureyev, Harvey Keitel, Ian McShane

The Western world is breaking down. Socially, politically, economically, morally, aesthetically and psychologically. Really, if you look into your own lives there are only two routes of escape from this dark claustrophobic trap: art and romantic love. In the novel you are supposed to read by Monday, The Sorrows of Young Werther, Goethe through his art reveals not only the ecstasy of romantic love but also the doomed consequences that necessarily follow. Driven by his excruciating passion to the brink of suicide, Werther, the novel’s hero, says to Charlotte: “Your hands have grasped these pistols, you have wiped them for me, those hands from which I’ve longed wish to receive my fate.” This language is straight from the German romantic tradition of the 19th Century, but the sensibility is of our time. As Leslie Fiedler writing about Werther comments: “Here is the final twist, the theme of the redeeming maiden, woman who was the angel of redemption becomes the angel of death. But for Werther, death is redemption. The only salvation he can use.”

That indigestible gob of exposition – delivered by writer/director/producer Toback himself, no less, in his role as an English literature professor – opens the film, and it’s soon painfully obvious that those are the themes which will be explored over the next 95 minutes. You’d be better off saving yourself the bother, and sticking with the Cliff Notes version above, rather than enduring this remarkably non-thrilling thriller, which should be Exhibit A for any film-maker who thinks it’s a good idea to wear as many hats as Toback. For the odds are, if someone else had been producing or directing this, rather than the writer, the massive flaws in both central aspects of the story, would have been noticed and addressed. Instead, producer Toback signed off on writer Toback’s script, and director Toback then assiduously committed the idiotic concepts it enshrines to celluloid. There was, apparently, no-one involved with the production, who was capable of raising their hand to go, “Hang on a minute…”

We’re neck-deep in “Kinski + older men” territory here; the three with whom her character is involved are played by actors who average 20 years her senior. The first is the professor mentioned above, Leo Boscovich, who basically stalks student Elizabeth Carlson (Kinski) out of college and back to the Wisconsin farm where she tells her parents she’s going to head to New York. On arriving, she soon gets treated to the scummier side of the city, being robbed on arrival, but things take a turn for the better when she’s discovered by photographer Greg Miller (McShane), while working as a waitress in a cocktail bar – sorry, my inner Human League escaped for a moment. One quick montage later, she’s a top supermodel, whizzing all over the world. However, she is also being stalked again, this time by Daniel Jelline (Nureyev), a violinist who eventually tells her he is hunting a terrorist called Rivas (Keitel). Rivas is obsessed with Carlson, and Jelline wants to use the model as a lure, to bring the international criminal to justice.

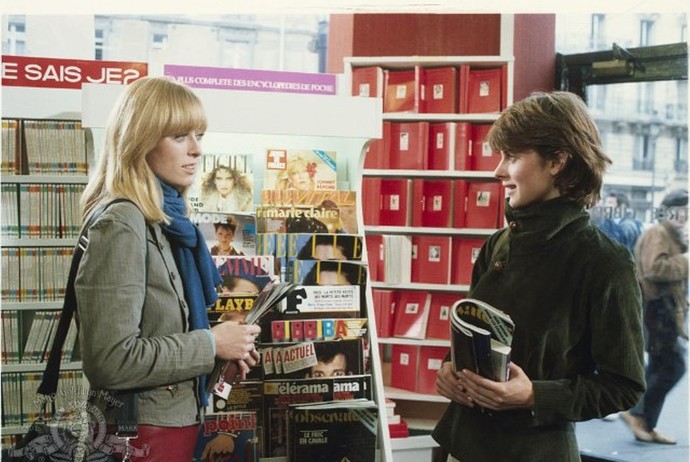

One of the IMDB reviews is headlined “Nastassia Kinski: Super Model/Terrorist Hunter,” and damn, I’d watch that film in a heartbeat. Unfortunately, that falls into the category of technically correct, but wrong on all the important details; in particular, the ludicrous way in which things unfold. The first main issues is the Elizabeth/Daniel relationship. Apparently, the way to a supermodel’s heart is to babble surreal nonsense at her, then walk away, followed by breaking into her apartment. That’ll hook her. Then, you leave incriminating documents around your apartment, fabricate an entirely fictitious backstory, because a relationship built on one-sided dishonesty can’t possibly fail? You’ll soon be running your violin bow all over her body. No, that’s not a euphemism for a body part: as shown on the left, one scene has Nureyev literally playing Kinski like a Stradivarius. I can only presume it looked better in the script.

Equally as daft is Elizabeth’s infiltration of the terrorist cell. Coincidentally, we watched an episode of Homeland immediately after, which has a rather more credible depiction of the uber-paranoid nature of terrorist cells. I dunno, this was the eighties, maybe that came with kinder, gentler terrorists as well as big hair. That seems the only conclusion, because it only takes our heroine a 15-minute chat and a McDonald’s value meal before she’s being led straight to the group’s hideout, where Rivas is planning a massive atrocity. What does he want? Well, Toback covers that as well, with a speech, which might have sounded better if you think of it being delivered by Dennis Leary, in the style of Demolition Man: “I’ll tell you what I want. Good food. Women. Good cigars. Good beds with fresh sheets. Hot showers in Hilton Hotels. New shoes, poker, blackjack, dancing. Clint Eastwood westerns. That’s what I want. And you.”

Eventually, Elizabeth leads her two lovers to face each other, leading to a chase past various Paris landmarks, and through remarkably-empty streets (no, really: I’ve been there, many times, and this might possibly be the least-plausible part of the entire movie), before a shootout by the Seine. If you want to figure out how everything ends, go back and re-read the opening quote again, because the movie basically spoilers itself at the beginning. It’s a shame it finished, because I would love to be a fly on the wall when Elizabeth tries to explain everything that happened to the French police. Maybe Toback was saving that for the sequel, Exposed 2: Supermodel in Jail. Heck, I’d certainly have been up for watching that, and Kinski could have used her experience from juvenile jail as a 15-year-old.

You might have been able to tell, but I didn’t enjoy this one very much. The main issue is the script; it appears to know as little about women, as it does about international terrorism: it might have helped if Elizabeth had been given a personal reason to take down Rivas, rather than the hand-me-down revenge providing motivation. But it’s not helped by Nureyev’s performance, which is stilted and entirely unconvincing. He seems to have realized these deficiencies, too, because he hasn’t appeared in another movie since, ending a career which started – and, to be honest, peaked – with his title role in Ken Russell’s Valentino. Keitel starred in Toback’s directorial debut, Fingers, five years earlier, and is his usual reliable self; it’s possible to see why the members of his gang are so committed to him, and he possesses the cold ruthlessness necessary for the role.

Kinski, however, is as worth watching as ever, and the film certainly works best when the focus is on her. There’s an early scene where she’s playing the piano to try and get a job, and she’s forgotten none of the training needed for Spring Symphony. Later on, alone in her apartment, Elizabeth is dancing around to the original version of The Shopp Shoop Song by Betty Everett – she’s a fan of that era’s music – and the unfettered joy that comes across is enough to drive from your brain, all thoughts of Cher’s shitty cover and the execrable Mermaids which included it. While I certainly can’t agree with Jeremy Richey’s assessment of the movie, where he calls it “close to being a major masterpiece,” and an incredibly inventive film,” I do concur there are numerous aspects of the character she plays, that must have resonated with Nastassja, such as a controlling father. He also points out “the near disgusted and exhausted look” Kinski gives when someone compares Elizabeth to Garbo, Lombard and Monroe. To me, it seemed to be her thinking, “Not that shit again…“ Ah, the perils of being beautiful. I’ll finish with a quote from Greg Miller’s character, along the same lines:

Different clothes, different looks, different selves – you thought you knew who you were. Now? You’re not so sure- everybody else is intrigued. Men inventing fantasies about your eyes, your hair, your month, your skin, dreaming about what it’s like to touch you. Women, posing in front of mirrors, thinking what it’s like to be you. And you, saying to yourself, “What do they see? What do they see. What do they see…”