Dir: Margaret Koval

Star (voice): Salome Jens, Ian Richardson, Nastassja Kinski, Leslie Caron

This eight-part documentary series focuses on the period of World War I, from 1914-1918, and also covers the period leading up the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand which kicked things off, and also the chaos which followed the official cessation of hostilities in November 1918. It won two Prime-Time Emmys in 1996, one for Outstanding Informational Series, and the other going to Jeremy Irons for Outstanding Voice-Over Performance. He was just one of a host of famous names who did voice work in the series. Liam Neeson was Adolf Hitler, for example, with Ranulph Fiennes, Helena Bonham-Carter and Gary Oldman among many others involved. Narration was provided by Dame Judy Dench – well, except in the US, where she was replaced, for some reason, by Jens.

This eight-part documentary series focuses on the period of World War I, from 1914-1918, and also covers the period leading up the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand which kicked things off, and also the chaos which followed the official cessation of hostilities in November 1918. It won two Prime-Time Emmys in 1996, one for Outstanding Informational Series, and the other going to Jeremy Irons for Outstanding Voice-Over Performance. He was just one of a host of famous names who did voice work in the series. Liam Neeson was Adolf Hitler, for example, with Ranulph Fiennes, Helena Bonham-Carter and Gary Oldman among many others involved. Narration was provided by Dame Judy Dench – well, except in the US, where she was replaced, for some reason, by Jens.

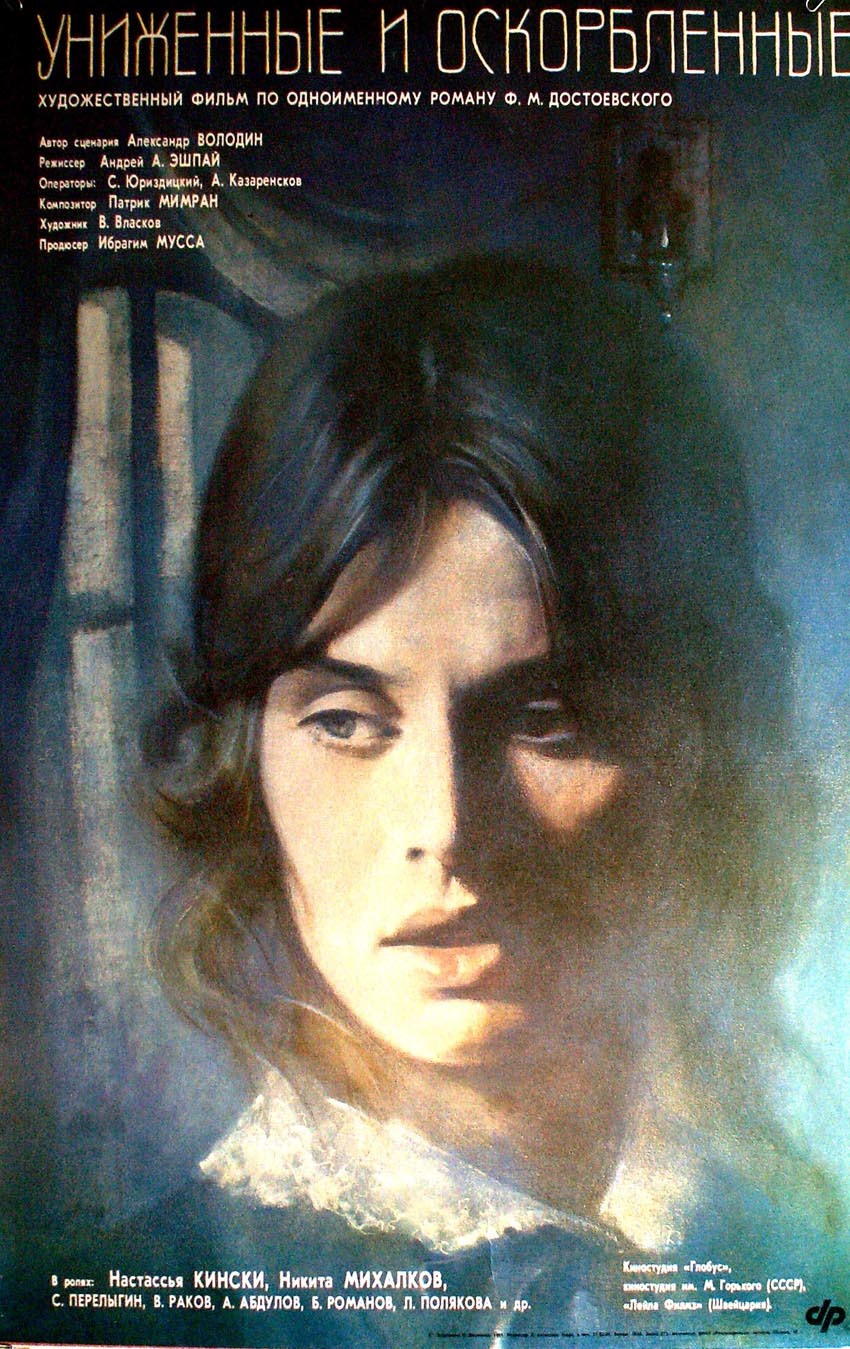

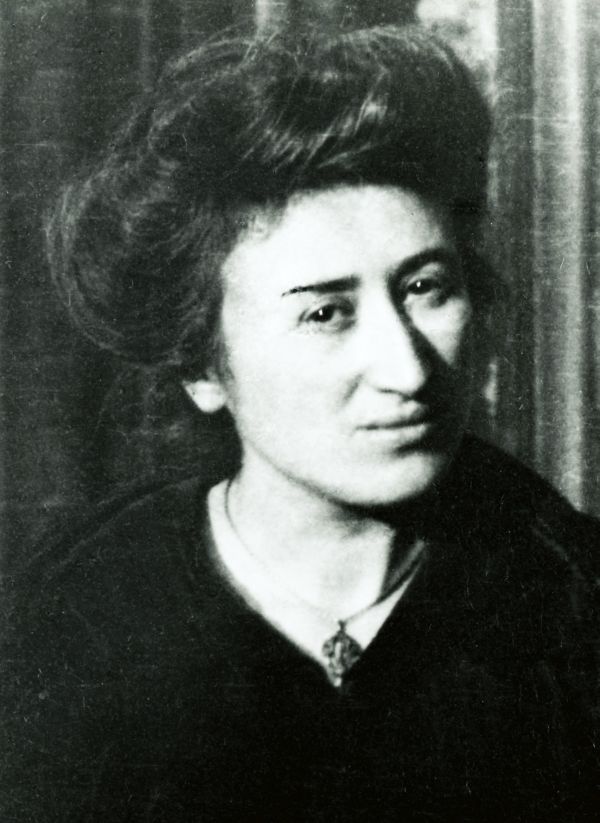

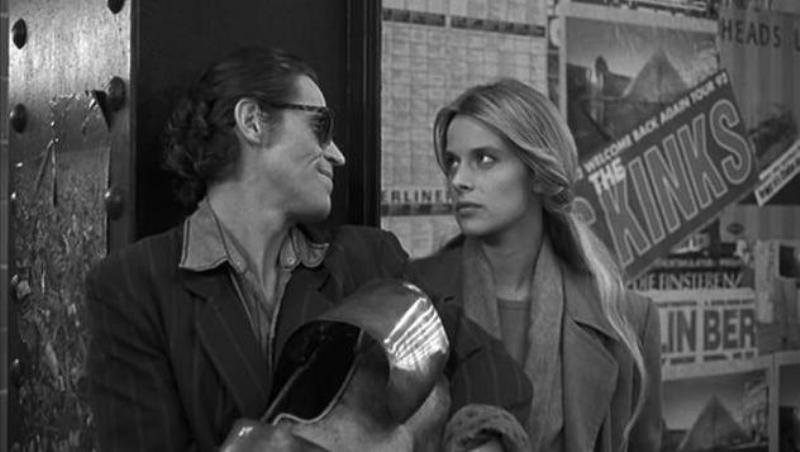

The seventh episode takes up after the guns fell silent, and starts by covering the ongoing struggle in Russia, where the new Bolshevik government was fighting a civil war against the White Russians. They also captured the ruling Romanovs, and uses the words of Czarina Aleksandra Romanov (Caron) to tell the story, leading up to the family’s execution. It then switches to Germany, a nation in hardly any less chaos, to tell the story of Rosa Luxemburg (Kinski), a revolutionary socialist whom the documentary says was “the equal of Lenin or Trotsky.” Imprisoned for the last two and a half years of the war, she resumed her political activities on her release. Despite misgivings, she supported the Spartacist uprising promoted by her lover, Karl Liebknecht, After the rebellion was ruthlessly crushed, she was captured, interrogated and, eventually, shot, her body dumped into a canal.

I recognized Kinski’s voice immediately, which is more than can be said for just about anyone else in this episode – and that includes other well-known names, including Martin Sheen, Martin Landau and Ned Beatty. Of course, Kinski had, more or less, cornered the market on German actresses known outside their native land – at the time of the documentary, it was probably her or Hanna Schygulla. Though having the very French Leslie Caron play the Tsarina, suggests true authenticity was not perhaps required. The rest of the documentary discusses the civilian toll due to famine, disease, etc. in post-war Europe, some of which was inflicted on the losers, to encourage them to accept settlement on the victors’ terms. There’s also discussion of the difference in approach to the negotiations taken by America and the colonial powers like Britain in France; the United States wanted self-determination for all, while the European nations were more interested in preserving their empires. My, how times have changed…

And that is as close as you’re going to get to political commentary on this site. It’s not an era with which I have much familiarity, so I certainly learned a lot, though the production falls a bit on the dry side. Not sure things really benefit much from the celeb voice-cast; while good enough, I can’t say I was blown away by any of them in terms of emotion: I also might have preferred Dame Judi doing the narration, but then she is a National Treasure. Definitely a nice change of pace for NK though; if they ever do a biopic version of Luxemburg’s life, maybe they could get Nastassja to play her? Below you can find the audio of the relevant section from the documentary, so you can enjoy her sultry tones.

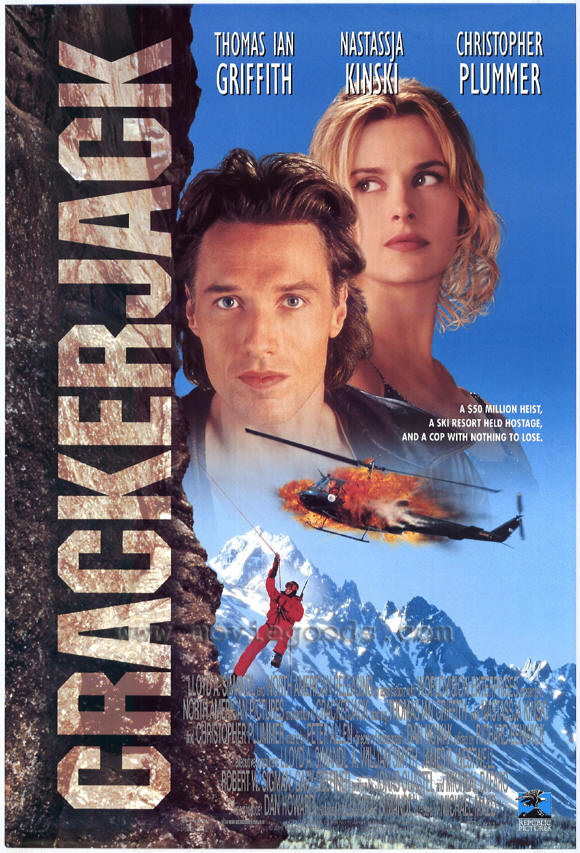

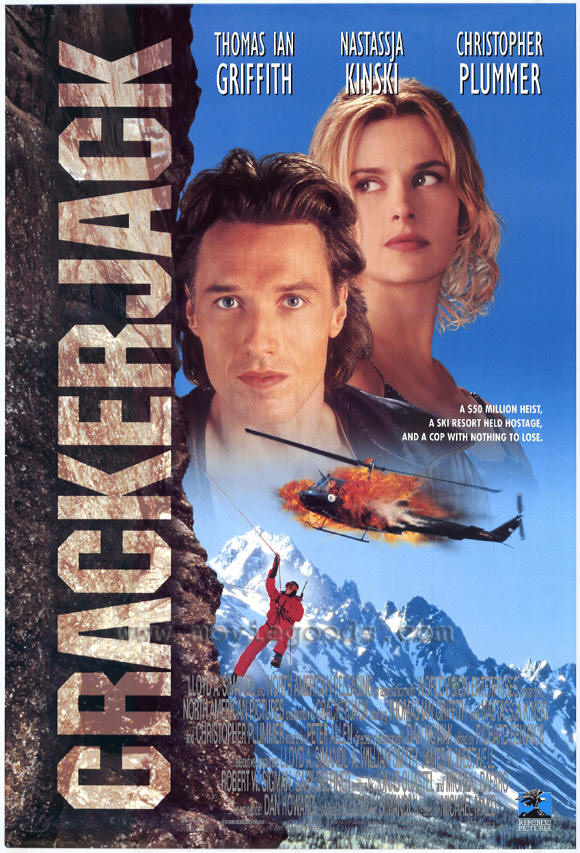

After parachuting his guys in, for no readily apparent reason [I’m fairly sure Jack, Mike and Anne didn’t get to the resort by jumping out the back of a plane. Well, Mike and Anne, anyway – Jack’s a wild and crayzee guy], Getz kicks his scheme into action. Jack is out on the balcony enjoying a quiet perv at a couple in a neighboring room, so manages to avoid the room-to-room sweep of the terrorists. From there, you would be entirely better off removing this video-cassette from your VCR [kids, ask your parents!] and slapping in Die Hard instead. I’ve no problem with taking the concept and giving it a new twist, but the makers don’t bring anything new to the party here. Plummer is actually not bad, but Alan Rickman was just so good as the Euro-villain, it renders every effort to go down the same route pointless. But at the risk of stating the obvious, the biggest difference is that Griffith is no Bruce Willis. with a career apex probably marked either by this or John Carpenter’s Vampires. It isn’t much of a contest.

After parachuting his guys in, for no readily apparent reason [I’m fairly sure Jack, Mike and Anne didn’t get to the resort by jumping out the back of a plane. Well, Mike and Anne, anyway – Jack’s a wild and crayzee guy], Getz kicks his scheme into action. Jack is out on the balcony enjoying a quiet perv at a couple in a neighboring room, so manages to avoid the room-to-room sweep of the terrorists. From there, you would be entirely better off removing this video-cassette from your VCR [kids, ask your parents!] and slapping in Die Hard instead. I’ve no problem with taking the concept and giving it a new twist, but the makers don’t bring anything new to the party here. Plummer is actually not bad, but Alan Rickman was just so good as the Euro-villain, it renders every effort to go down the same route pointless. But at the risk of stating the obvious, the biggest difference is that Griffith is no Bruce Willis. with a career apex probably marked either by this or John Carpenter’s Vampires. It isn’t much of a contest.

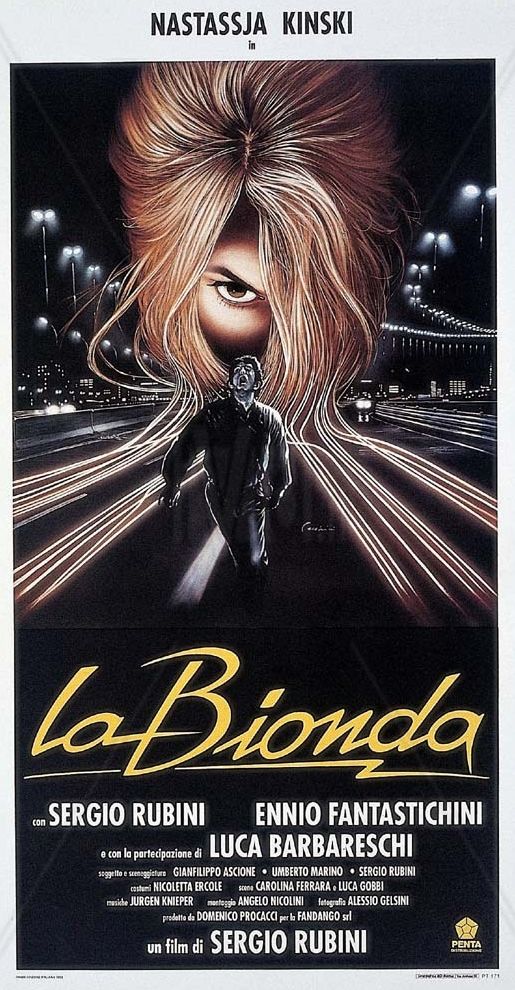

Things perk up a bit for the finale, though you do have to suspend your disbelief significantly. Milan is not exactly a small city, and one can presume its airport is similarly-sized. But the three protagonists here miraculously arrive at the same place at the same time, as if this was a one-gate facility in rural Montana. They then whizz off down a highway which is also so completely deserted, you wonder if the rapture had occurred. There’s not even anyone to be seen, driving past on a moped going “Ciao!” [Bonus point to you if you get that reference] Well, right up until the end, when the 16-wheeler necessary to the plot suddenly appears, like a diesel-powered deus ex machina, to tidy up the loose ends, and do what Tommaso apparently is unable to. As an aside, should mention on the copy I was watching, the audio was significantly out of sync with the video. For most of the film, that didn’t matter, because it was subtitled anyway, so that was in sync. But during the action finale, you’d have Nastassja apparently screaming her lungs out, with nothing to be heard, save the roar of the engines. It actually added a kinda surreal beauty to proceedings, like a waking nightmare.

Things perk up a bit for the finale, though you do have to suspend your disbelief significantly. Milan is not exactly a small city, and one can presume its airport is similarly-sized. But the three protagonists here miraculously arrive at the same place at the same time, as if this was a one-gate facility in rural Montana. They then whizz off down a highway which is also so completely deserted, you wonder if the rapture had occurred. There’s not even anyone to be seen, driving past on a moped going “Ciao!” [Bonus point to you if you get that reference] Well, right up until the end, when the 16-wheeler necessary to the plot suddenly appears, like a diesel-powered deus ex machina, to tidy up the loose ends, and do what Tommaso apparently is unable to. As an aside, should mention on the copy I was watching, the audio was significantly out of sync with the video. For most of the film, that didn’t matter, because it was subtitled anyway, so that was in sync. But during the action finale, you’d have Nastassja apparently screaming her lungs out, with nothing to be heard, save the roar of the engines. It actually added a kinda surreal beauty to proceedings, like a waking nightmare.