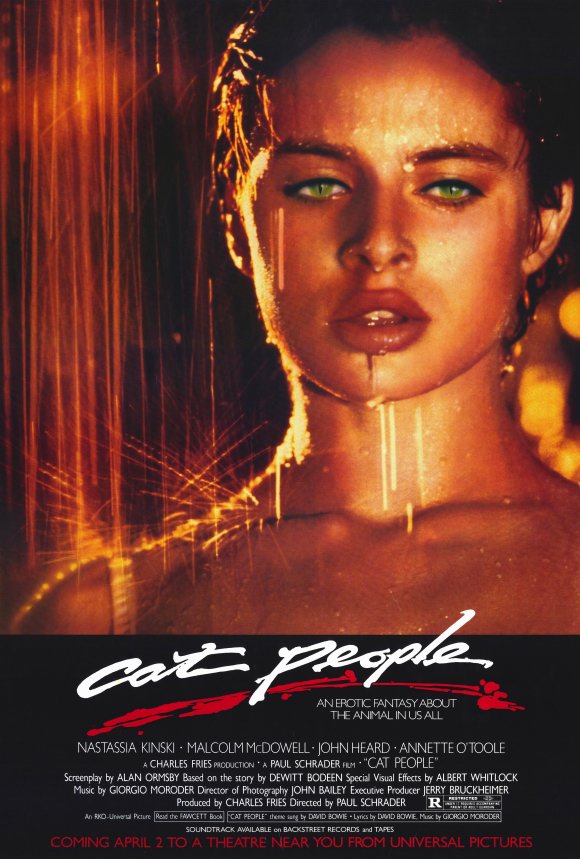

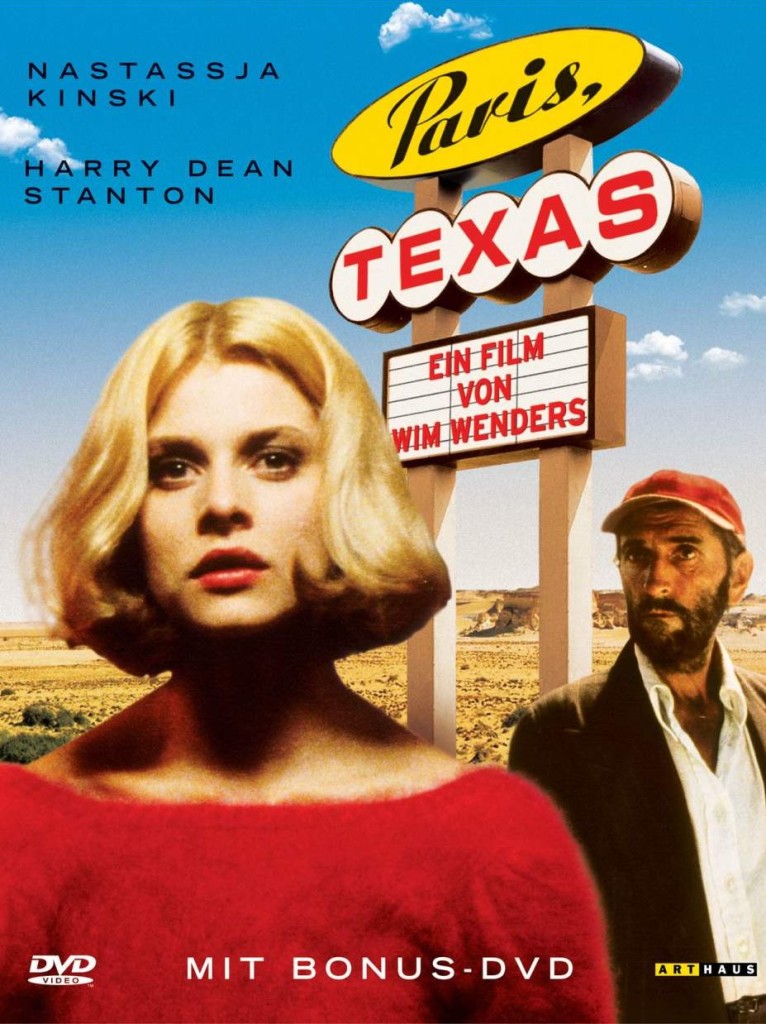

Dir: Wim Wenders

Star: Harry Dean Stanton, Dean Stockwell, Hunter Carson, Nastassja Kinski

The first time I saw this was, approximately, 1985. At the time, I was a student at Aberdeen University in Scotland, and had not even been to America at that stage. Now, I’ve been living in Phoenix for more than 13 years, which is somewhere in the middle of the two main locations depicted by Wenders – Houston and Los Angeles – and contains elements of both. This may help explain why I appreciated the setting rather more now, Wenders bringing a fresh, European eye to the landscape in which this European is now located, and depicting how the quest for the American dream can turn in to the American nightmare. Even little things, like a scene set at the Cabazon dinosaur roadside attraction, later made famous in PeeWee’s Big Adventure, demonstrate the director’s eye for the different.

The first time I saw this was, approximately, 1985. At the time, I was a student at Aberdeen University in Scotland, and had not even been to America at that stage. Now, I’ve been living in Phoenix for more than 13 years, which is somewhere in the middle of the two main locations depicted by Wenders – Houston and Los Angeles – and contains elements of both. This may help explain why I appreciated the setting rather more now, Wenders bringing a fresh, European eye to the landscape in which this European is now located, and depicting how the quest for the American dream can turn in to the American nightmare. Even little things, like a scene set at the Cabazon dinosaur roadside attraction, later made famous in PeeWee’s Big Adventure, demonstrate the director’s eye for the different.

Travis Henderson (Stanton) staggers out of the desert and collapses. He’s carrying a business card belong to his brother, Walt (Stockwell), who travels from his Los Angeles home to collect Travis, despite his ongoing effort to keep walking, heading to an initially unknown destination, later revealed to be the city of Paris, Texas, where Travis has a vacant lot. Initially, he won’t even speak to his brother, but as the pair drive back to LA – Travis refusing to fly – he opens up, at least somewhat, though the question of where he has been for the past four years, remains unanswered. He disappeared after he and his wife, Jane (Kinski), had split up, leaving their son, Hunter (Carson), who barely remembers his father, for Walt and his wife Anne (Aurore Clement) to take care of.

Slowly, Travis reconnects with his son, and tries to remember what it’s like to be a “good father.” Anne reveals to Travis that Jane got her to set up an account for Hunter, and has been depositing money in it on the same day every month, from a bank in Houston. Driven by his new-found sense of paternal responsibility, Travis sweeps up Hunter and drives half-way across the country to stake out the bank, and wait for Jane to arrive. They almost miss her, but are able to trail her to the dubious establishment where she now works, setting up an incendiary and bitter-sweet reunion – or confrontation, it’s hard to be sure.

Having been thoroughly unimpressed with Falsche Bewegung, I wasn’t sure I’d be able to sit through the near-140 minute running time here, but it proved more a pleasure than a chore. The main reason is Stanton, who delivers a wonderful and touching performance, taking a tragic and deeply-flawed figure, and imbuing him with almost heroic qualities of self-sacrifice and dogged perseverance. Stockwell, too, does a very nice job as the dutiful brother: let’s face it, if a sibling dumped a four-year-old on my doorstep, the first call would be to Child Protective Services! Walt certainly goes above and beyond, and it’s a shame he is entirely forgotten for the second half of the film, as the scenes of the brothers’ road-trip were perhaps the ones I liked best, even if not possessing the emotional punch of those between Stanton and Kinski.

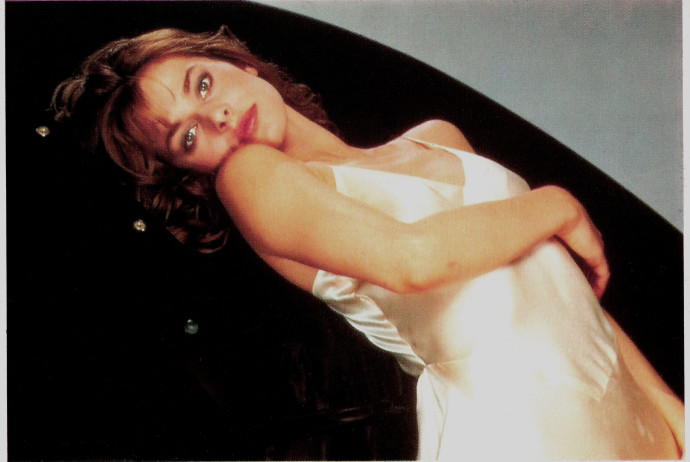

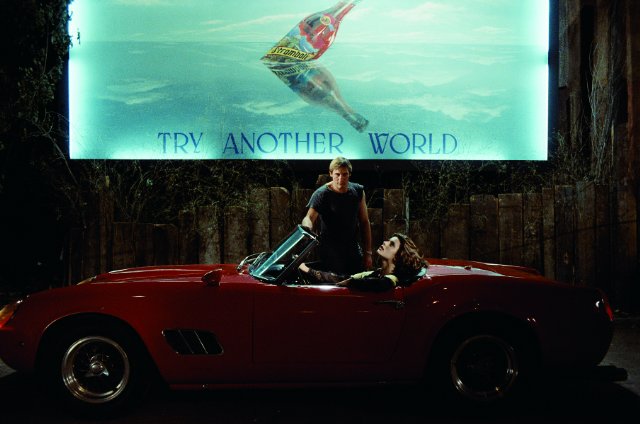

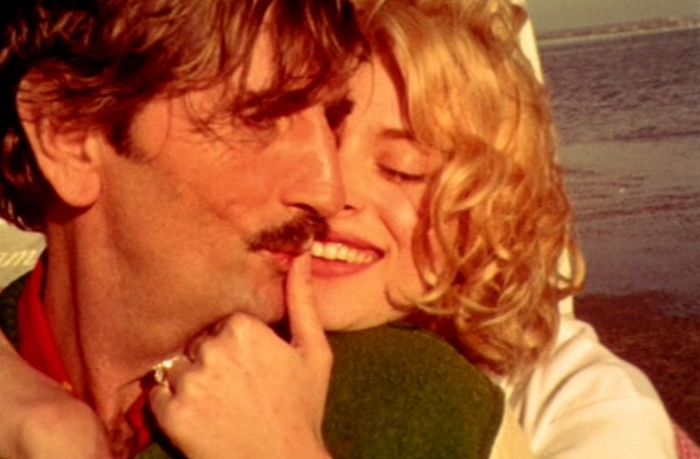

Kinski’s role is an odd one: she’s clearly pivotal to the drama, yet you’re a long way in to the film before she makes her first “live” appearance, discounting her scenes in old vacation footage watched by Travis, Hunter, Walt and Anne. Still, her radiant presence there (right) harks back to an earlier time, when she and her husband were genuinely happy. It’s perhaps seeing this which stars Travis on his doomed – perhaps emotionally suicidal – quest for redemption and to be reunited with Jane. But it’s the scenes where they face each other, separated by one-way glass, that pack the real wallop, laying their souls bare to one another, in a way they were unable to when they were actually together. Shot in long, unflinching takes by Wenders, it’s uncomfortable viewing, due to the raw intensity of the feelings being expressed.

Kinski’s role is an odd one: she’s clearly pivotal to the drama, yet you’re a long way in to the film before she makes her first “live” appearance, discounting her scenes in old vacation footage watched by Travis, Hunter, Walt and Anne. Still, her radiant presence there (right) harks back to an earlier time, when she and her husband were genuinely happy. It’s perhaps seeing this which stars Travis on his doomed – perhaps emotionally suicidal – quest for redemption and to be reunited with Jane. But it’s the scenes where they face each other, separated by one-way glass, that pack the real wallop, laying their souls bare to one another, in a way they were unable to when they were actually together. Shot in long, unflinching takes by Wenders, it’s uncomfortable viewing, due to the raw intensity of the feelings being expressed.

Two aspects on the technical side must be mentioned, because they are absolutely integral to the film’s success. The first is cinematographer Robby Müller, who gives the landscape of tarmac and power-lines an almost mystical feel, turning everyday objects into a magical land, which Travis occupies, rather than living in. The other is Ry Cooder’s soundtrack, which almost becomes a character in its own right, and is based on Blind Willie Johnson’s Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground – interesting to note that Wenders would go on to make The Soul of a Man in 2003, a documentary film focusing on Johnson. Here, Cooder’s score does a magnificent job of capturing the loneliness of the long-distance walker that is Travis.

Finally, L.M. Kit Carson, the father of Hunter, took on the task of beating Sam Shepard’s work into shape, after filming had already started. According to Carson, the set-up in place when he took over was radically different:

[Wim] says, “I set up a great mystery at the beginning of this film, and then I explain it.” I said, “Okay, what are you talking about?” So he told me the two scripts that he had from Sam. One was a script where Nastassja [Kinski’s] father was a big Texas oilman like J.R., and he sent his goons, and they beat up Harry Dean [Stanton] and took her and put her in a penthouse in Houston. And the other version of the script was Nastassja’s mother was under the spell of a televangelist, who of course, in the great tradition, ran whorehouses and drug dens. So he sent his goons to beat up Harry Dean, and took Nastassja and put her in a whorehouse. Those are two versions, and how they separate, and how Hunter ended up living with his brother.

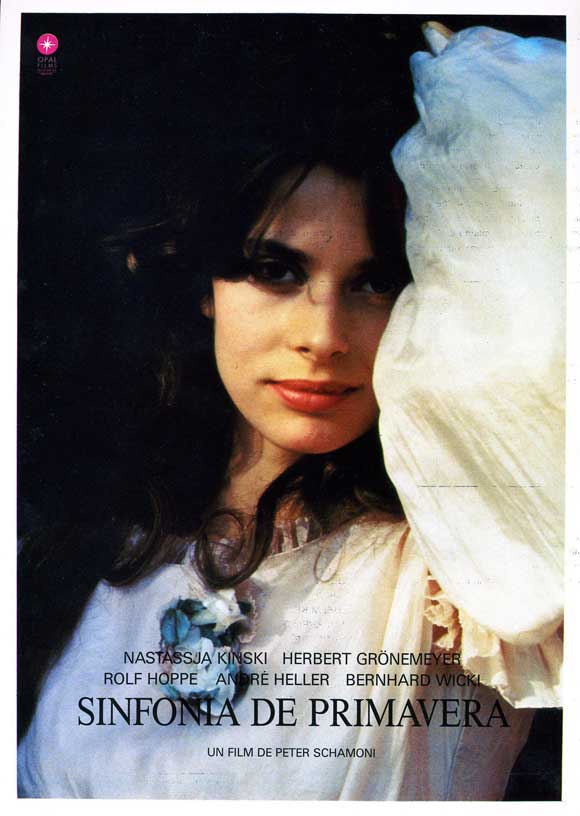

I can’t help wondering what might have happened had Wenders filmed those original versions offered up by Shepard. Still, as is, it remains a genuine classic, and if it’s not top of my personal list, you can certainly see why it’s the highest-rated Kinski film on the IMDb. If anyone ever tries to claim Kinski can’t act, this should be Exhibit A in your counter-argument.

“Ms. Kinski’s bear costumes by Richard Tautkus.” That is, I feel fairly confident in saying, a unique credit in cinematic history. However, I can’t say I was too impressed by a film which seems largely like a Hollywood liberal’s wet-dream, nodding its head at the entire gamut of sexual relations, from inter-racial through homosexual to incest. Except rape. For some reason, they draw the line there. I’m still not sure of the era in which the body of the film is supposed to take place. It appears the early stages, where Win Berry (Bridges) marries Mary, are set before the war, which would make the main section, with the oldest kids in high school… the late fifties or early sixties? Maybe the novel is clearer, but otherwise, it seems a much-more tolerant era than I’d heard.

“Ms. Kinski’s bear costumes by Richard Tautkus.” That is, I feel fairly confident in saying, a unique credit in cinematic history. However, I can’t say I was too impressed by a film which seems largely like a Hollywood liberal’s wet-dream, nodding its head at the entire gamut of sexual relations, from inter-racial through homosexual to incest. Except rape. For some reason, they draw the line there. I’m still not sure of the era in which the body of the film is supposed to take place. It appears the early stages, where Win Berry (Bridges) marries Mary, are set before the war, which would make the main section, with the oldest kids in high school… the late fifties or early sixties? Maybe the novel is clearer, but otherwise, it seems a much-more tolerant era than I’d heard.

Unfaithfully Yours

Unfaithfully Yours The Hotel New Hampshire

The Hotel New Hampshire